In the United States during early twentieth-century, diseases like typhoid, diphtheria, consumption, and yellow fever rippled through the population. Psychiatrists of the era tried to connect the ways in which these endemics were related to mental health issues, specifically, insanity caused by “social maladjustment and even unhappiness.” Clinicians saw a rise in alcoholism and divorce, falling birthrate and a lowering of moral standards in society. They saw people choosing vice, feminism, and “the disintegrative forces of industry,” as root causes of collapsed family structures. This also led to a swell in nativist beliefs as people blamed the spread of infections on poor Black, Italian, Polish, Jewish families who recently migrated to Connecticut. The cultural authority that psychiatry now possesses was established in the early decades by men like Elmer Southard, director of The Boston Psychiatric Hospital, A Warren Stearns, esteemed psychiatrist, and Robert Yerkes, psychologist and professor at Yale University. The rise of experts, social control, and a medical ethos fit perfectly within the framework of eugenics ideology.

A term coined by Sir Francis Galton in 1883, ‘eugenics’ is the study of how to control and arrange reproduction to “breed” or “breed out” heritable characteristics deemed desirable or undesirable. Experts did not have a devised and coordinated strategy to breed a new society, rather, it gradually transpired in day-to-day practice. Doctors and researchers created a discipline that categorized human behavior into standardized arrangements which designated and dictated what were normal and abnormal ways of being. Abnormality, which in their view threatened the very fabric of western society, included: neurodivergence, homosexuality or gender expression, developmental disabilities, and dangerous or erratic behavior. The asylum system became the site of adjusting and altering people’s behavior into normalized arrangements.[1]

Eugenics ideology compounded on itself over four decades and pervaded throughout fields of scholarship, policy and practice. It established heredity as a cornerstone of diagnosis in Connecticut’s mental health systems. There are countless examples of racial science throughout the field of psychiatry in the early twentieth century; it was a thought process that was malleable, built to fit and suit a specific narrative which thereby constructed a method and a science of disdain. How did eugenics ideology influence mental health treatment and transform society spatially? The nuanced complexity of this history requires a deeper analysis of power structures and their expressions. It is not enough to identify that these institutional systems once existed and that people experienced oppression as a result. By examining Connecticut’s mental health history through the lens of biopower and biopolitics, it exposes the systems of domination designed for the control of marginalized peoples.

Michel Foucault’s theories of biopower and biopolitics are a blueprint for this historical inquiry. According to Foucault, ‘biopower’ organizes human subjects as a population and ‘biopolitics’ is concerned with regulation and control of that population through the medicalization and subjugation of bodies. Eugenics was ingrained spatially into the field of mental health by using policy and scholarship to justify the construction of asylum institutions, the isolation and sterilization of people with disabilities, limiting immigration, even proposing mass executions.

Exploring sources pertaining to the Connecticut State General Hospital for the Insane (now Connecticut Valley Hospital) in Middletown, reveals the ways in which the hospital was used as a site for segregating people deemed “unfit” for public life. The state employed mechanisms of biopower to control the birth rate of specific classes of people through policies like the 1909 law “An Act concerning Operations for the Prevention of Procreation,” which enacted a sterilization policy for inmates in state asylums and prisons. An article from The Hartford Courant documenting the deportation of two immigrants hospitalized at the General Hospital for the Insane, exposes the biopolitics in Connecticut which manipulated the movement of people and their access to medical care. Lastly, a 1921 Hartford Times exposé entitled “Should the Hopelessly Insane Be Put to Death?” unmasks the ultimate expression of power the state held over disabled bodies. The sources elucidate the normalization of eugenics ideology in early twentieth century Connecticut. It became so commonplace that their legacies still reverberate in modern society and continue to produce harmful outcomes for communities of people. Critically examining eugenics in the foundations of psychological treatment identifies the mechanisms of biopower deployed over people with disabilities and its political repercussions.

According to Michel Foucault, political power in a capitalist society has the power to administer life and views the body as an apparatus for labor. The body’s regulation, the development of its capabilities, the coercion of its efforts, the simultaneous increase of its utility and its docility, its assimilation into systems of profit-making controls, characterized what he called an “anatomo-politics of the human body.” These are definitive features of biopolitics, the regulatory controls of human bodies. Biopower is the many processes enacted to actualize the coercion of bodies and the control of populations.

Foucault states that biopower is essential in a capitalist system; people’s bodies are only viewed as a means of production and economic growth. If the body is not serving financial gains, then it no longer serves a function in society. Institutions of power ensured the development and maintenance of techniques of power; the military, schools, the police and hospitals, operate in this domain of profit-making processes. These techniques of power also served as “factors of segregation and social hierarchization, exerting their influence on the respective forces of both these movements, guaranteeing relations of domination and effects of hegemony.” Institutional sites, such as mental asylums and prisons, became sites to isolate people who deviated from the norm or who were deemed “unfit” to participate in the labor economy.[2]

Dr. Abram Shew, the first superintendent of the Connecticut General Hospital for the Insane, described the history and layout of the institution in a July 1876 journal article published in the American Journal of Insanity. Situated in Middletown, one and a half miles from a range of hills known as the White Rocks, Shew asserted the hospital was more favorably located than older institutions. While the hills were destitute of soil and vegetation, there were springs and streams which passed into the Connecticut River. A sewer and water drainage system were designed to fertilize the soil and the patients would work the land to make it farmable.[3] They believed productivity and labor was a marker for wellness, additionally, their efforts would generate profits for the hospital. The asylum’s investment in bodies to increase the volume of capital assets of the institution facilitated a distributive management system that sustained itself. Indeed, Foucault identifies biopower’s expansion of differentiated allocations of profit and its varied forms of application. “The investment of the body, its valorization, and the distributive management of its forces were at the time indispensable.”[4]

In the interior of the hospital, Shew characterized its architecture as “rigidly plain,” and outlined the layout in great detail. Men’s and women’s wards were on opposite ends of the hospital with separate recreation centers. Activities like a billiards room and bowling alleys were available for “those who are sufficiently restored to understand and enjoy the play.” Rooms for patients identified as “seriously ill” were further cut off from human contact, designated to single rooms, down isolated hallways. Shew outlined the configuration of secluded chambers: “The lower stories are used as wards for excited patients. The rooms on each side of the corridor are fitted with window shutters hinged and locked with a separate hot air flue for each.”[5]

Completely sequestered from the external world, it solidified the relations of domination between doctor and patient at the Middletown hospital. A biopolitical form of power is about the regulation of social life and social engineering. People who exhibited signs of mental illness were removed from their communities and made into patients. They were then run through a system of intake procedures to categorize and itemize their capabilities in accordance to economic and social demands. If a person was authorized as rehabilitative, they were allowed to work the grounds and enjoy state-approved recreation. If they were marked as incurable, they were constrained in solitary confinement as not to “infect” the others. The Middletown hospital became the site to devise the conditions of subjectification that demanded an individual work on themselves and society, and if they could not, they were forced into varying degrees of confinement.[6]

A New Haven Register article, “Escapes From Insane Asylum,” published in November 1896, further illustrates the systems of biopower ingrained in Connecticut’s mental institutions prior to the turn of the century. Three men identified as Peters, Castagretti, and Hurley, escaped from the State Hospital for the Insane and were all formerly incarcerated at the state prison in Wethersfield. While the headline suggested it was a report on the escapees, the majority of the article was concerned with the conditions of the hospital and drew explicit comparisons between the hospital and the prison. The columnist argued the General Hospital for the Insane was no place for a convicted criminal, as the surveillance and security of the institution was lower than that of the prison. They cited the latest escape as a reason to open the debate as to whether incarcerated people with mental illness should even be given treatment in Middletown in the first place. The article exemplifies the symbiotic relationship the hospital had with the prison. They identified approximately forty individuals who are classified as “criminally insane:” someone accused of a crime and acquitted for mental incapacity. At the time, the hospital had a convict ward, which was originally designed to be a carpentry workshop. Due to overcrowding and a heightened demand to transfer incarcerated individuals to the hospital, the space was repurposed.

To mimic the conditions of a prison as much as possible, the ward was fortified with bars and strengthened to prevent escape. “Specially appointed attendants have charge of the patients in the convict ward and, aside from the necessary modifications entailed by the fact that they are under treatment for insanity, the convicts are treated about the same as they would be were they still in prison.” This statement is peculiar when one considers the original intention of the hospital: to provide compassionate care for those in need. Instead, the hospital’s convict ward echoed the environment of a penitentiary. In the concluding arguments, the author cited an upcoming General Assembly meeting as the perfect time to begin discussing a solution. They suggested enacting a law requiring all people convicted of a crime to stay at the prison whether they were deemed insane or not. Framed as an economic solution, they proposed an insanity ward within the prison and would transfer them when they exhibited signs of illness.[7]

According to researcher Dr. Daniel HoSang, there is a direct connection between incarceration and medical care. There are overlapping forms of control, as a hospital has the biomedical power to assert domination over people’s bodies. This is like the state-sponsored violence found in prisons, as people are forced to surrender their autonomy.[8] The New Haven Register article illustrates how state-funded institutions removed people from their communities and constrained their bodies in penal confinement; the Middletown hospital and Wethersfield prison were reciprocative. In biopolitics, the juridical system of the law is part of the mechanisms to regulate and correct those who transgress against the norm; biopower is the action of the norm. The apparatuses of the judicial institutions are then incorporated into multiple forms like the hospital and the prison to enforce a normalized society. Their structures fortified to ensure confinement for those who wish to escape. The asylum and the prison fed on each other to measure, qualify, and hierarchize people in accordance with the law of the norm. Biopower takes control of the “delinquent” person’s life and grants itself access to their body.[9]

Throughout early-twentieth century life, it was the dominant belief that people living with mental illness were best left in the care of the asylum system and away from the general population. This was reflected in both government policy and in published media. In 1919, Governor Marcus Holcomb appointed The Connecticut Infirmary Commission to “investigate and advise on the segregation of delinquent, feeble-minded and criminally insane persons.” The commission consisted of state hospital superintendents which including Dr. F.W. Wilcox of Norwich State Hospital and Dr. Charles P. LeMoure of Mansfield Training School.[10]

A year later, the State Board of Charities approved establishing another state-funded infirmary for “diseased, deformed and incurable persons for whom no treatment is available in existing institutions.” The Infirmary Commission deliberated with Governor Holcomb on a site to erect the institution. They visited various state institutions to determine where they would add this new building. Upon visiting the Reformatory at Cheshire, board member Elliot Watrous remarked, “The presence of a certain number of men who are mentally deficient was manifest, and something should be done, in my opinion, to permit of segregation from the rest of the inmates, and I believe that there is under consideration a plan to erect a separate building in an enclosure, as a hospital and sanitorium for such unfortunates.”[11] Confining people with severe disabilities in isolated corridors of the state hospitals wasn’t enough; the state needed a completely separate site altogether. Exclusion and prevention were the driving forces behind Connecticut’s biopolitics.

Newspapers like The Bridgeport Telegram, promoted a national effort towards the segregation and sterilization of people with disabilities. A column published in February of 1923 lauded the sterilization law proposed in Chicago Federal courts. The Telegram advocated for, “segregation as a means for protecting society from dangerous criminals and at the same time preventing them from reproducing their kind, has in recent years been accepted as the most necessary step in crime prevention.”[12] Biopolitics approaches the population as a political problem that is scientific, biological, and the state’s problem. Framing criminality and disability as a social disease and a hereditary trait, practitioners of eugenics promoted isolating maladjusted people and prevented procreation as a means of controlling their natural environment.

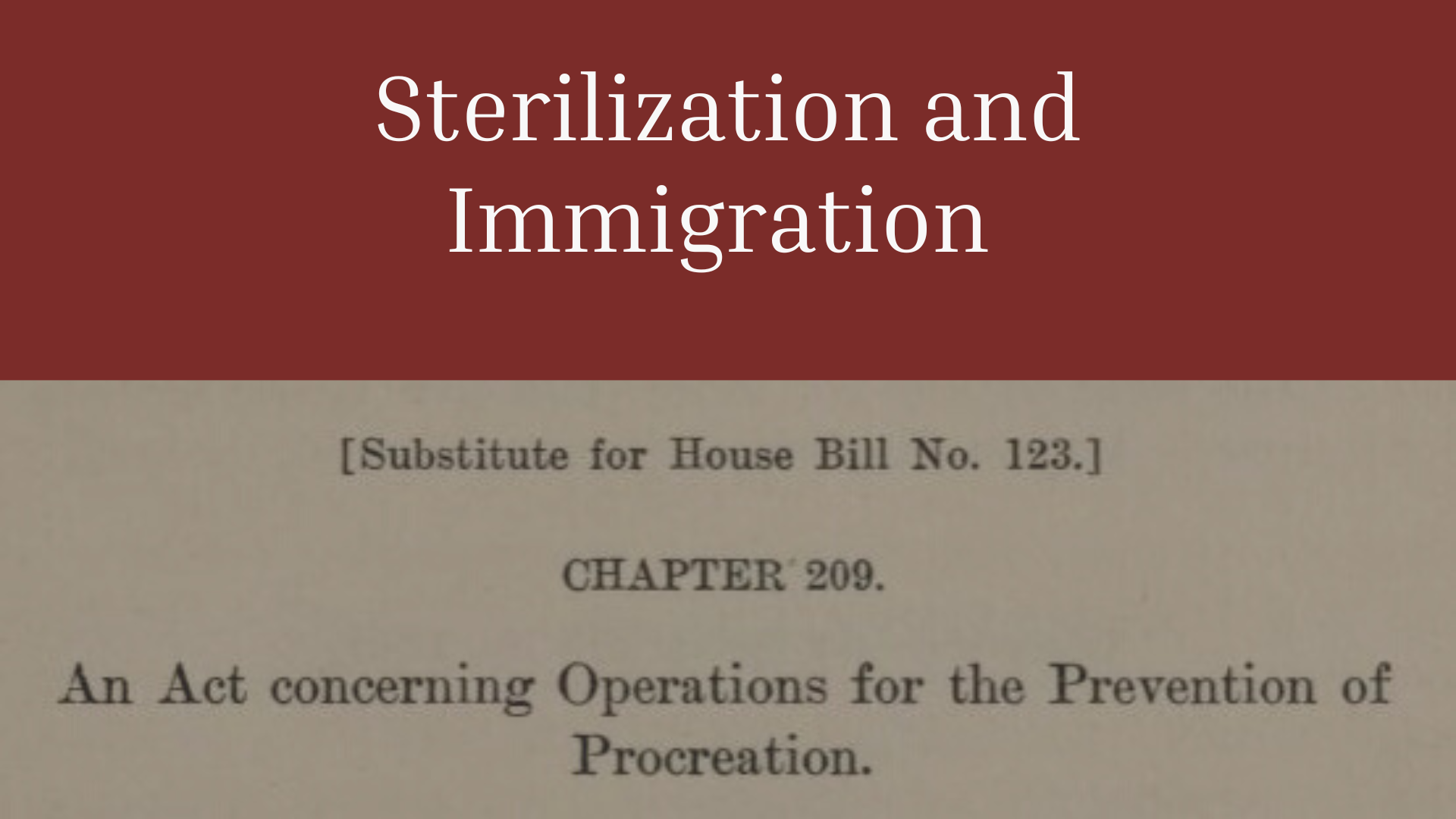

Connecticut passed its sterilization law in 1909 for people deemed by the state as “unfit” for procreation. The law defined unfitness as, “procreation by any such person would produce children with an inherited tendency to crime, insanity, feeble-mindedness, idiocy, or imbecility, and there is no probability that the condition of any such person so examined will improve to such an extent as to render procreation by any such person advisable… then said board shall appoint one of its members to perform an operation of vasectomy or oophorectomy…”[13]

It was one of the first sterilization laws in the country, second only to Indiana. In the first decade of its passage, there were few victims. By 1920, funding was allocated for the law and thus, a system of suppression was established in the state. Between 1909 and 1963, approximately 557 people were sterilized; ninety-two percent were women. Seventy-four percent were identified as mentally ill, and twenty-six percent were considered “mentally deficient.”[14] The law was only applicable to people being held in state prisons, the hospital for the insane in Middletown, and Norwich state hospital. In the 1919 amendment, the law expanded to encompass Mansfield State Training School and The Hospital at Mansfield Depot.

The ideological campaigns and political operations which emphasized morality and responsibility spread this “technology of sex.” Sterilization was one of many tactics to discipline the body and regulate populations. According to Foucault, “In the name of the responsibility they owed to the health of their children, the solidity of the family institution, and the safeguarding of society. It was the reverse relationship that applied in the case of birth controls and the psychiatrization of perversions.”[15] In order to control the population by subordinating people’s bodies into medical procedures, sex was the crucial target in the state’s management of life. Biopolitics, however, is reliant on multiple institutions to enact its science of disdain and domination. Academic institutions like Yale University were sites of legitimization for the biopower of eugenics.

In 1926, the American Eugenics Society and The Race Betterment Foundation were established in New Haven and founded by Irving Fisher, an economics professor at Yale. In addition to Fisher, Robert Yerkes was a professor in psychobiology, and the founder of mass aptitude testing.[16] The American Eugenics Society (AES) published a 1931 pamphlet entitled, “Organized Eugenics.” The booklet promoted legislation in Connecticut relating to the “segregation of certain socially inadequate persons,” and eugenic sterilizations for people they designated “hopelessly unfit.” People with hereditary mental illness, developmental disabilities, and epilepsy fell on that list. They also supported laws relating to marriage, contraceptive information, and Federal immigration restriction.

Using Biblical verses to justify their reasoning, they cite Matthew 7:18; “A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit.” Using people’s genealogical history against them, AES devised a system for measuring human social fitness by using race and ethnicity, IQ, citizenship status and family health history as metrics. They emphasized the purpose and mission of eugenics as being “concerned with the influences which affect the inborn, hereditary quality of the population.”

Throughout the pamphlet, there was an interest and emphasis on immigration, that highlighted the intersection of mental health, immigration and racism in the biopolitics of eugenics. AES supported a racial and ethnic hierarchical structure that gave academic legitimacy to limit immigration and control the transnational movement of bodies. “The eugenicist is interested in immigration regulation in relation to its bearing upon the racial and family-stock quality of future generations of Americans.” Their Committee on Selective Immigration promoted the exclusion of specific groups of immigrants and believed that selective immigration was a solution to quell the number of people who became the public charge.

They instructed policy-makers to only admit those who they deemed superior to the average American as proven by psychological tests. They also backed overseas medical inspection to prove “highest possible degree of efficiency” and consider hereditary history. Lastly, they cited a “rigid enforcement” of a public charge clause and emphasized policies of “occupational selection” or “industrial need.” They claimed fifty years of research demonstrated “plans for economic and biological selection of immigrants” were necessary for national success.[17] AES, along with organizations throughout the country, solidified a normalization of eugenics as a valid method of biopower for states to deploy.

The rhetoric advocated by The American Eugenics Society was not the first of its kind in the state of Connecticut. In 1903, State Comptroller William E. Seely deported two immigrants who were committed to the State Hospital for the Insane. In an article published in The Hartford Courant, it described Seely’s actions as a way to “prevent the state’s becoming the dumping ground for demented immigrants.” A man and a woman with three young children, with no relation to one another, both passed inspection at Ellis Island and arrived by ferry to Bridgeport. The article does not state where the man or the woman settled, nor where they were from, but did specify they eventually were committed to the Middletown Asylum. Their admittance was noticed by Comptroller Seely who launched an investigation. Immigration policy at the time did not allow people with mental illness or disabilities to enter the country, let alone receive state-funded treatment. Seely communicated with the steamship company that brought them over and arranged for their immediate deportation. This also raised suspicion of other “demented pauper immigrants” residing in the state and pronounced efforts to find them and send them back to their native countries.[18]

The racialized policy which controlled the movement of immigrant bodies is at the heart of eugenics and biopolitics. In this hierarchical structure, immigrants with disabilities are at the bottom tier; their lives and contributions were deemed valueless in the economic system that viewed them as parasitic. They did not qualify to be confined in the asylum and were sent back on the very steamships that brought them to New York. This likely compounded whatever mental health issues they were experiencing, further evidence the state’s intent was to control populations, not to provide access to care.

In 1921, Connecticut lawmakers earnestly debated whether it was merciful or not to execute low-income people living with mental illness. A column published in The Hartford Times, entitled “Should the Hopelessly Insane Be Put to Death,” documented a committee of State Legislators who visited Norwich State Hospital. The superintendent, Dr. F.W. Wilcox, gave them a tour. After seeing the conditions, they raised the question whether it was more ethical to execute people rather than attempt to provide care.

“If a dog goes mad we shoot him. If a horse breaks his leg he is instantly killed; a horse’s leg cannot be successfully mended. Thus we spare these dumb animals in the one case the miserable existence of madness confined in a cage, and in the other case the wretchedness of dragging out a useless existence with more or less pain and suffering. Should the same line of reasoning and action be applied to human beings?”

The lawmakers pressed through the door of a small, padded cell where they observed a man strapped to the bed. It was then that one of the lawmakers exclaimed, “I would rather be dead than lead such an existence.” Another added, “Certainly death would be preferable.” This opened a dialogue surrounding the ethics of execution as if it was a humanitarian effort. “What we have seen here to-day raises the question in my mind if we ought not to present a bill to the Legislature providing that the hopelessly insane may be lawfully put out of existence.” Following that, they discussed possible safeguards to protect those that have a chance of being cured from their illness. The author cited the Bible as a justification to defend the lawmaker’s argument. To them, Christian scripture was used countless times in the past to justify the death penalty. The exposé documented various patients’ diagnosis and characteristics with salacious detail. From a modern-day lens, it reads as gratuitous and exploitative, despite the author’s intentions to grip the reader with a sense of pity and compassion for the individuals described.

“Night and day their screams ring in her ears and her poor, shattered mind pictures them beaten and starved and shockingly abused. She calls aloud for help, appeals to anyone she may see to save them, and when her crying has exhausted her, sinks into a moaning, gasping, troubled sleep. Not a thought for herself. She seems to have forgotten her own existence; a striking example of the maternal instinct surviving the wreck of all else that was human in her.”

They asserted if one spends enough time with a person who is mentally ill, they too will develop some sort of insanity, suggesting that mental illness is a communicable disease.[19] As medical historian Alexandra Minna Stern outlines, eugenic ideology was always linked to fears of biological degeneracy and pursued efforts towards genetic purification.[20] While many were in agreement, this proposal was not unanimous among the legislative committee. Lawmakers like Senator Edward F. Hall and the chairman Representative Robert O. Eaton both agreed the action was humane, but posed it as impractical because it went against the values of Christianity.

Senator Charles M. Bakewell, the head of the philosophy and psychology department at Yale said, “Put human nature being what it is, and human knowledge being what it is, I for one should not like to vest such power in any individual or group. I will say, however, that it is not a matter unworthy of consideration, for it is a revolutionary proposal, a proposal to take life for the benefit of the killed rather than the killer.” Even if he wasn’t completely against hearing out the argument, Bakewell identified the danger behind the policy. He posed the philosophical dilemmas that arose with eugenics; the potential for abuse and how authoritarian politics could facilitate genocide.

Emily Sophie Brown, member of the House of the Committee of Humane Institutions was the loudest in disagreement of this proposal. She posed the questions; how can one truly know someone is “hopelessly insane?” If there was a quantifiable way to measure that, how does one fully know the extent of their suffering? Brown also pointed out that the proposal does not address the heart of the matter, which is providing adequate care. Lastly, she highlighted the timeline of mental health practice and asserted that there’s so much more to learn about the human mind. “…the study of the mind is in its infancy, and that if we only persist, we shall sometime know so much about diseases of the mind that we would no more think of executing an insane person that we would of killing a sufferer from adenoids.”[21]

When one traces the line of eugenics, the logical conclusion is almost always a promotion of erasure and eradication of specific groups of people. As Foucault outlines, this power and function of death exercised in a biopolitical system is centered upon racism. There is an illusion of a biological distinction of races which establishes the hierarchy in which one group is treated as inferior, a tool to further separate the population. By defining some groups as biologically inferior it suggests they are a subspecies. He describes biopower logic:

“The more inferior species die out, the more abnormal individuals are eliminated, the fewer degenerate there will be in the species as a whole, and the more I-as species rather than individual- can live, the stronger I will be, the more vigorous I will be. I will be able to proliferate. The fact that the other dies does not mean simply that I live in the sense that his death guarantees my safety; the death of the other, the death of the bad race, of the inferior race (or the degenerate or the abnormal) is something that will make life in general healthier: healthier and purer.”[22]

In Clare Henson’s essay “Biopolitics, Biology and Eugenics,” she points out, “for Foucault ‘race’ is an extraordinarily mobile category which is continually being ‘reconverted’ and reinscribed.” State racism sprang forth from a belief that abnormal people and immigrants are enemies to the biopolitical system. “The imperative to kill is acceptable if it results in the elimination of the biological threat…”[23] This demonstrates it was likely if a state-sponsored execution program was implemented, it would be along racial lines. The 1921 article framed its endorsement of state-sponsored murder as an act of compassion, but in actuality, it was a verbalization of biopower. State lawmakers possessed the power and authority to discuss the mortality of human lives and determine whether someone could be reformed or not, or whether someone’s life had value. Corrigibility and heredity were the deciding factor for a person to present a biological danger to larger society. Debates over systematic genocide was the response to prevent the risk of spreading “degeneracy.”

Throughout life in Connecticut, eugenic ideology shaped systems of biopolitics throughout the state. Asylums like the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane were sites to confine and segregate people deemed mentally unfit to participate in public society. Published scholarship from organizations like The American Eugenics Society influenced public policy and media, giving scientific legitimacy to a politics of contempt. The sterilization of incarcerated people and people living with mental illness or developmental disabilities, allowed the state to exercise its biopower, attempting to control the birth of future populations. A decade after the law was passed, state legislators ventured to justify executing severely disabled people altogether.

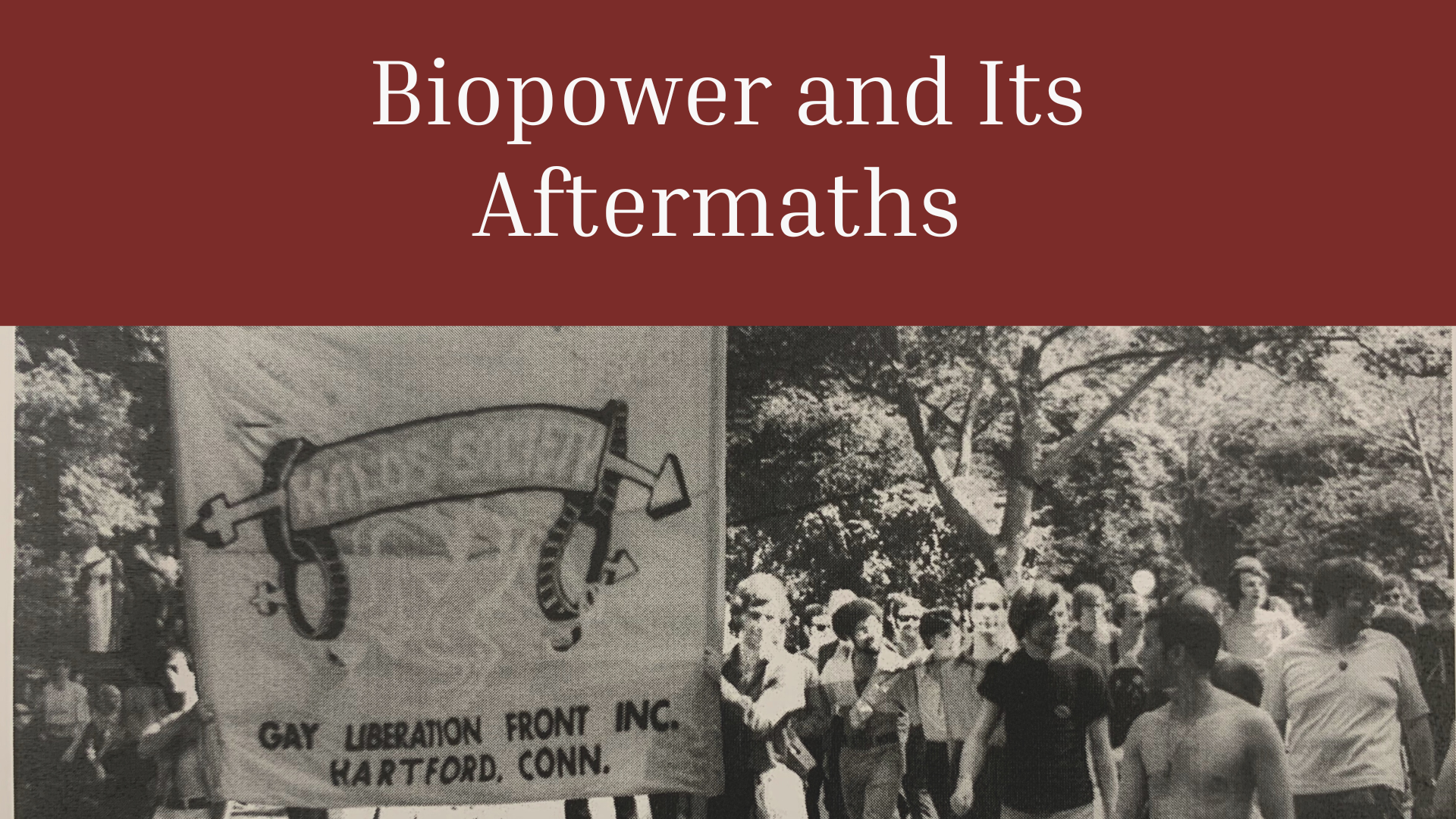

The biopower mechanisms in the state deployed policy backed by racialized science, and molded knowledge-power into an agent of rearranging human life. Marginalized peoples faced the very real process of struggle as their lives were viewed as a political commodity. However, people “turned back against the system that was bent on controlling it.”[24] Resistance to biopower existed throughout this era. There were organizations and coalitions of people centered on a mission towards advocacy, support, and community care. Resistance to eugenics comes in many forms but the common theme is that it is rooted in undermining the abuse of power. Multi-ethnic, multi-racial organizations were part of Connecticut’s vibrant resilience culture history. While resistance culture pushed back tirelessly, this research illustrates the pervasive nature of eugenic science which was forged into foundational principles of mental health research and practice. From forced sterilizations to discussing the ethics of executing people with mental illness, eugenics was a ubiquitous form of biopower in Connecticut’s modern history.

Reference Footnotes:

[1] Lunbeck, Elizabeth, The Psychiatric Persuasion: Knowledge, Gender, and Power In Modern America, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1994) 11-25.

[2] Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality Vol 1, Part 5: Right of Death and Power Over Life. https://monoskop.org/images/4/40/Foucault_Michel_The_History_of_Sexuality_1_An_Introduction.pdf, (accessed November 22, 2022), 46-48.

[3] Shew, Abram Marvin, “History and Description of the Connecticut Hospital for The Insane,” American Journal Of Insanity, (July 1876). 15-17.

[4] Foucault, Michel, pg. 46.

[5] Shew, Abram Marvin, pg. 10-12.

[6] Foucault, Michel, pg. 46.

[7] “Escapes From Insane Asylum,” New Haven Register, November 15, 1896, CVH Scrapbooks: Departments of Mental Health CSHI/CVH Records, A. Superintendents Scrapbooks Ca. 1867-1896, Accession #90-018, Box 1, Connecticut State Library.

[8] HoSang, Daniel Martinez, A Wider Type of Freedom: How Struggles for Racial Justice Liberate Everyone, (Oakland: University of California, 2021), 117-118.

[9] Foucault, Michel, pg. 47-48.

[10] “Governor Appoints Commission on Insane,” The Hartford Courant, May 21, 1919. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/governor-appoints-commission-on-insane/docview/556691582/se-2 (accessed December 9, 2022).

[11] “State Infirmary Formed,” The Hartford Courant, December 20, 1920. Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/369320921/. (accessed December 9, 2022).

[12] “Sterilization Court For Unfit is Chicago Plan,” The Bridgeport Telegram, February 1, 1923. Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/paper/the-bridgeport-telegram/636/. (accessed December 9, 2022).

[13] “An Act Concerning Operations for the Prevention of Procreation,” (Laws of Connecticut Affecting Insane Persons, Connecticut, 1909), pg. 84. Connecticut State Library.

[14] Kaelber, Lutz, University of Vermont, Connecticut Eugenics, 2012. https://www.uvm.edu/~lkaelber/eugenics/CT/CT.html. (accessed November 1, 2021).

[15] Foucault, Michel, pg. 50.

[16] Hutchins Center, “Legacies of Eugenics in New England Conference: Part 1,” YouTube video, 2:00:03-2:29:18, September 23, 2021, https://youtu.be/cEN5aWmuE0k. (accessed November 1, 2021).

[17] American Eugenics Society, Organized Eugenics, (New Haven: American Eugenics Society, 1931) x-22.

[18] “Insane Immigrants: State Doesn’t Want That Kind of Public Charges, Hartford Courant, April 22, 1903. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/insane-immigrants/docview/555132949/se-. (accessed December 8, 2022).

[19] “Should the Hopelessly Insane Be Put to Death?” Hartford Times, February 27, 1921, CVH Scrapbooks: Departments of Mental Health CSHI/CVH Records, A. Superintendents Scrapbooks Ca. 1867-1896, Accession #90-018, Box 1, Connecticut State Library.

[20] Minna Stern, Alexandra, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in America, (Oakland: University of California, 2016), 11.

[21] “Should the Hopelessly Insane Be Put to Death?” The Hartford Times, February 27, 1921, Connecticut State Library.

[22] Foucault, Michel, pg. 52.

[23] Henson, Clare, “Biopolitics, Biology and Eugenics,” in Foucault in An Age of Terror, ed. Stephen Morton and Stephen Bygrave (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 106-108.

[24] Foucault, Michel, pg. 48.