Intersectionality. You’ve probably heard the buzzword, but what is it? And how does it connect to history?

“A quest to reveal the gendered and colonial thinking in the field of historical analysis.”

As a historian, I was a little shocked to see that there’s not much in the historical field that discusses applying intersectional theory with historical inquiry. There’s plenty of historical literature that addresses themes of intersectionality, but there’s very little out there that explicitly grapples with the concept. But first things first, I need to make sure you have a clear definition of what intersectionality is before we continue.

in·ter·sec·tion·al·i·ty

/ˌin(t)ərsekSHəˈnalədē/

noun

the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.

In other words, we all have a multitude of social identities, some of those identities may give us an advantage or a disadvantage, depending on the time and place. So how does this connect to historical research? Well for that I turned to one of the only scholarly articles on the matter entitled, “Intersectional history: exploring intersectionality over time” by Ellen Shaffner, Albert J Mills and Jean Helms Mills. According to them, “intersectional history combines intersectionality and the study of the past to examine discrimination in organizations over time.” Researchers will modify their approach depending on subject, but essentially we use the framework of intersectional theory to understand to analyze historical primary sources and find evidence of marginalization and resistance.

In many ways, intersectional history is the history of power, through the lens of marginalized peoples. There are some key points that historians need to keep in mind as they conduct their research:

- Focus on simultaneous oppressions

- Goal of understanding and reinterpreting history from the social locations of marginalized peoples

- A recognition and interest in women of color’s agency

- Attention to the role of the state and the interrelations between colonialism, racism and gender in women of colors’ lives

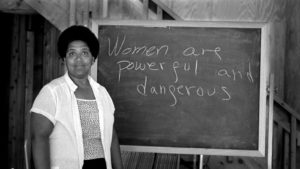

You may ask, why is there an emphasis on women of color in our research? Well, because intersectional theory was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw and it was explicitly written to understand the systemic social oppression that put Black women at a disadvantage compared to their male counterparts or white women. “Intersectionality… was borne out of this tradition of examining the experiences of Black women in relation to gender, race and class.”

It’s also important to note, there’s some debate in academic and advocate circles, as to how intersectional theory should be used in research. I have seen the argument from scholars that any theoretical framework discussing marginalized identities that does not include Black women, should not be considered intersectional. I’ve also seen the argument that the theory should not be applied beyond sociological research. However, I personally think expanding our understanding of the theory and applying it to historical analysis can allow us to rethink the dominant historical narrative.

“Some feel that intersectionality must be defined and bounded, whereas others, embracing a more post positivist notion of feminism and critical race studies, argue that intersectionality flourishes because of its resistance to a hegemonic, positivist notion of theory.”

Long story short, this historical research blog is devoted to investigating the history of diverging and overlapping identities; how people shaped history by resisting colonialism and white supremacy over the last five hundred years. While there is an emphasis on highlighting the experiences and struggles of Black women, the topics cover a broad range of identities and situations over time and space. Additionally, there’s an emphasis on American history (because that’s my specialization), but I strive to feature as many histories as I can expose myself to.