An effort to redefine American identity beyond the confines of colonialism and whiteness.

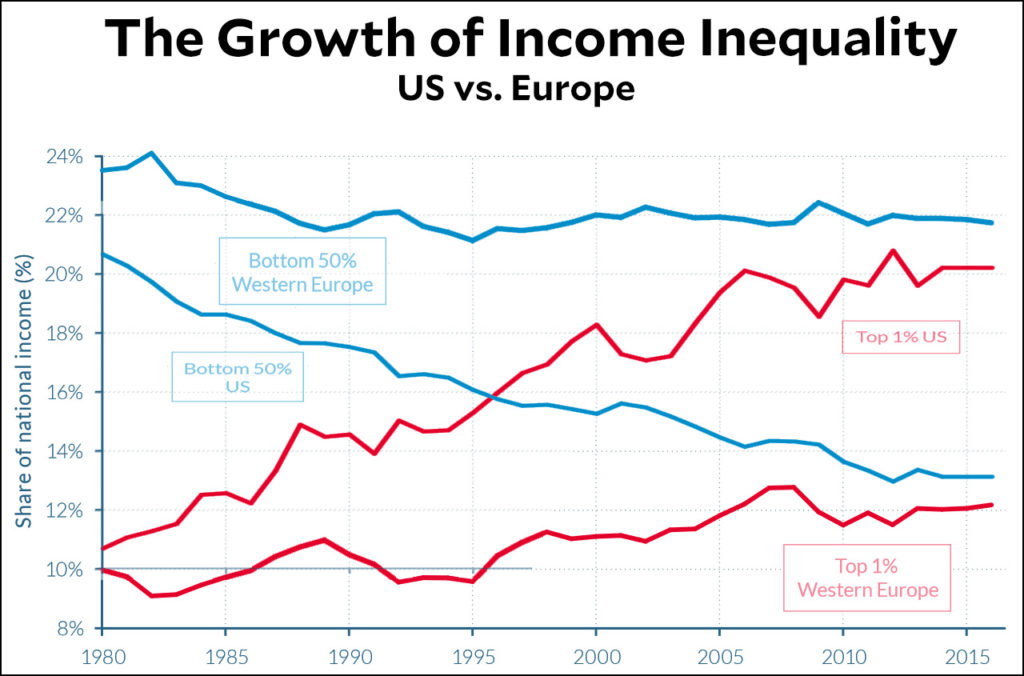

The notion of American identity is not a fixed concept. American identity ebbs and flows through time, with only one fixed idea: white men holding the vast majority of power. Many have attributed American identity to the pursuit of the “American dream.” It’s almost mythical in nature; the notion that entrepreneurial spirit and hard work will lead to a successful, fulfilling life. Even those for whom the myth was constructed for, white working-class Americans, have lost faith in the idea. According to PRRI (Public Religion Research Institute) and The Atlantic, nearly two-thirds (65%) of white working-class Americans believe American culture and way of life has deteriorated since the 1950s. Today, the United States labor market has tightened, as industrial and manufacturing jobs are disappearing, non-college whites particularly in rural and suburban communities feel left behind in the nation’s economy; expanding trade and technology are pushing them out of a job. And while that remains true, the racial wealth gap remains staggeringly large, with a typical white household having 16 times the wealth of the average Black family. “The median white household had $111,146 in wealth holdings in 2011, compared to $7,113 for the median Black household and $8,348 for the median Latino household.”

While there are many white Americans living in poverty, particularly in the Appalachian region, white Americans have more access to rise out of poverty and claim American identity. According to James Baldwin, “White children…whether they are rich or poor, grow up with a grasp of reality so feeble that they can very accurately be described as deluded-about themselves and the world they live in…the reason for this, at bottom, is that doctrine of white supremacy, which still controls most white people, is itself a stupendous delusion: but to be born Black in America is an immediate, a mortal challenge.”

As history indicates, however, even whiteness is not a fixed concept. Today, whiteness is attached to essentially anyone from Europe; it is seen in a more binary structure than it was in the past. That wasn’t always the case- in the 19th century racial hierarchies existed with Anglo-Saxon, WASPS, and Teutonic at the top, while Celtic, Mediterranean, Slavic and Hebrew were considered second-class white people. And even still, people of color; Black, Indigenous, Mestizo, Middle Eastern, Asian and Latinx people have experienced varying degrees of oppression all at the hands of white people in power. As a result of this, they have a greater hill to climb in terms of carving out identity in America, with their survival constantly being threatened.

“People of color have never been merely passive victims of white supremacist power…In the process of defending themselves and advancing their own immediate interests, individuals and communities struggling against white supremacy have often created ways of knowing, forms of struggle, and visions of the future important to all people.” The most effective theory to honoring and understanding the spider web of American identity is intersectionality. It is a tool to understand layers of gender, racial and economic justice; to investigate how different sets of identities impact one another with regards to access to rights and opportunities. It is also a way we can understand how power structures formed, providing a historical context and ultimately with this knowledge, creating advocacy and policy change.

It is impossible to investigate American identity without talking about slavery. According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, between 1525 and 1866, 12.5 million Africans were shipped to North and South America, and the Caribbean, 10.7 million survived middle passage. Only about 388,000 came to North America, the vast majority sent to the Caribbean and South America; Brazil receiving 4.86 million. Slavery was the foundation of capitalism which was the very reason Southern plantation owners were willing to wage war for it. But even in New England it was the basis of our modern economy. According to historian Lorenzo Greene, Connecticut’s insurance industry began with slave voyages; Aetna writing some of their first insurance policies on slave lives. Profits made from loans and insurance policies were then put back into Northern businesses.

Freedom is one of the buzzwords you’ll hear when someone is describing what it means to be American, which paradoxically is put up against the country’s history of slavery. “A notion of freedom lies at the core of the American idea of whiteness. Accordingly, the concept of slavery- at any time, in any society- calls up racial difference, carving a permanent chasm of race between the free and the enslaved.” After slavery was abolished, freed Black people were not in the clear and as we witness today; they are still faced with cultural second-class citizenship.

Sharecropping continued white dominance over Black workers, owning ⅔ of all profits, determined to make freedom as close to slavery as they could muster. In 1915, The Birth of a Nation, a film glorifying the Ku Klux Klan “became the biggest blockbuster film of it’s time, generating $60 million at the box office through just its first run” the film unified the nation both North and South in creating a mainstream culture founded on white supremacy. And while this is cancerously seen today almost on a daily basis, James Baldwin offers some wisdom on how dismantle it, “People who cling to their delusions find it difficult, if not impossible to learn anything worth learning: a people under the necessity of creating themselves must examine everything, and soak up learning the way the roots of a tree soak up water. A people still held in bondage must believe that Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make ye free.”

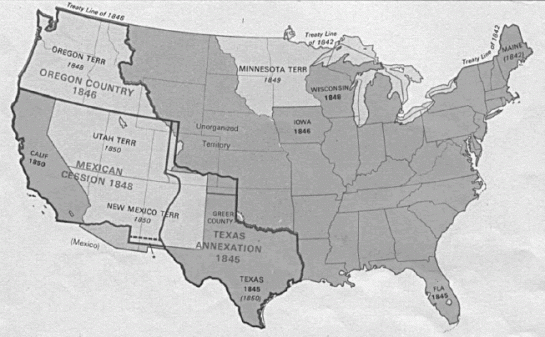

Spanish and English colonialism was also a pivotal part of both American and Mexican identity. 17th century Spanish missions held Indigenous people as slaves, whole populations decimated by disease. With this also came miscegenation, race-mixing. For many Mexicans in the twentieth century, mestizaje would be seen as a celebration of the creation of the Mexican heritage, but for many Anglo-Americans, it was seen as a social taboo and degeneracy. Manifest Destiny, the ideology that views Anglo-Saxons are uniquely destined to rule over other people, fueled the U.S.-Mexico War. The war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the United States acquired 525,000 square miles becoming modern-day California, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Nevada and Texas. Along the U.S.-Mexico border, the “tendency of simultaneous interconnection and division has characterized the relationship of the U.S. and Mexico for its entire history; reflecting an ambivalence between two pillars of capitalism and racism.”

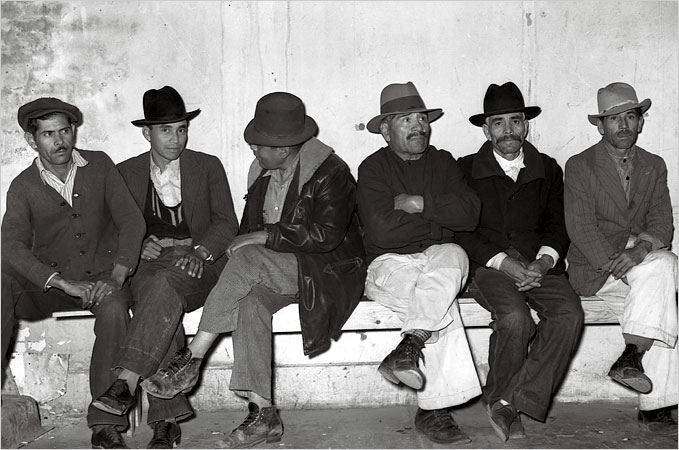

In Cochise county, a history of Anglo-dominance over land, resources and wages pushed Mexican-American and Apache residents out of the area but not without a fight. “The Apaches were at war to protect a homeland that had been theirs for hundreds of years before Cowboys or silver miners appeared.” For five years Chiricahua Apaches waged war with Anglo settlers and after surrendering in September 1886, every single man, woman and child of the Chiricahua tribe residing on the San Carlos reservation was deported to Florida’s Fort Marion and Fort Pickens. Mexican-Americans also faced deportation after unionizing and fighting the dual-wage system, in which Mexican-Americans were paid less than white Americans for the same work.

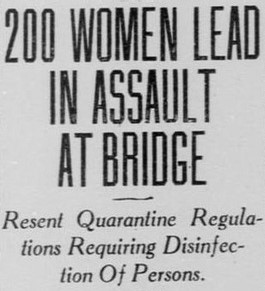

After a typhus outbreak in 1916, the U.S. government instilled a quarantine policy along the southern border, perpetuating the racist stereotype “dirty Mexicans.” Mexicans wishing to cross the border were forcibly stripped naked and doused in poisonous chemicals which included kerosene and Zyklon B. During this, people had been set on fire in an El Paso jail after being bathed in kerosene known as the Jail Holocaust. Carmelita Torres was a 17-year old maid seeking to cross the border from Ciudad Juarez to El Paso, Texas. She had heard of the forced baths and also knew of border agents taking photos of Mexican women as they were stripped down. On January 28, 1917, Carmelita refused the bathing process. Following her actions, she sparked women-led protests called the Bath Riots which eventually led to her arrest. Despite their efforts, the policy stayed intact until the late 1950s. Adolf Hitler had complimented the U.S. on their border quarantine policy- even modelling the use of Zyklon B in concentration camps.

Today, Cochise county still struggles with racial division and is one of the most heavily patrolled borders; law enforcement primarily concerned with drug and human trafficking. In 2016, Arizona state budget allocated $26.6 million to the Department of Public Safety and more specifically, The Border Strike Force- a partnership between local, state and federal law enforcement fighting drug and border crimes. And while the border of the U.S. and Mexico are the remnants of a war waged over 200 years ago, the Mexican heritage is integral to American identity.

Many immigrants, including my family, arrived in America believing this was a land of meritocracy; through honing your skills and working hard, one can rise to power. This is, sadly, another one of the mythical qualities of America.

While I can say on behalf of my personal experience, despite having no education or money, my family did okay. This was not the case, however, for many Issei immigrating from Japan, residing in Los Angeles at the turn of the 20th century. “Racial restrictive covenants prohibiting nonwhites from inhabiting houses provided the crucial instrument to advance residential segregation during the interwar period. Designed to evade the Fourteenth Amendment, restrictive covenants, unlike racial zoning, were attached to specific privately owned properties and deemed to be the actions of individuals rather than the state.” This forced Issei and Nisei to live in overcrowded, unregulated buildings.

Despite groups like the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) organizing mobility and addressing community concerns, xenophobia fueled anti-Japanese sentiment. The attack at Pearl Harbor only exacerbated this. “The impact of Pearl Harbor was dramatic and everlasting on the Nisei community.” After that, the case for internment was in mainstream rhetoric and eventually became a reality. In the spring of 1942, between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese descent were forcibly removed from their homes and put into prison camps. And while they paled in comparison to Germany’s concentration camps, the action left trauma on the Japanese-American heritage for generations to come. Chinese immigrants also faced hardships trying to establish themselves on American soil. They were the first immigrants that were restricted from coming to America with the passing of The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This barred Chinese men from working in mining as well as owning property and so many opened laundry services for mining workers. Emboldened by the Exclusion Act, white Americans pushed to boycott Chinese businesses, regardless if they were providing a valuable service or not. In Tombstone, Arizona, Anti-Chinese political parties sprung up.

Following the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, the efforts to desegregate schools and provide equitable education for Black Americans was undermined by the non-issue of busing. All throughout the 60s and 70s, white protesters took to broadcast media to frame desegregation as a threat to their children. Legislators used the distinction of de jure and de facto segregation as a means of getting around civil rights for Black Americans. Through restrictive covenants, zoning and infrastructure, white Americans were able to keep segregation alive without blatantly doing so. Denying Black and Latinx students the same access to education as white students, it left them in a disadvantage to rise out of poverty. Without access to educational programs and community efforts to improve neighborhoods, left children on the streets, susceptible to crime and incarceration.

These systemic foundations of our nation show that it is not merit that will allow someone to acquire the success they seek, but rather whiteness being the core deciding factor about how hard you’ll have to fight to get a piece of the pie. “Whiteness has a cash value: it accounts for advantages that come to individuals through profits made from housing secured in discriminatory markets, through unequal educations allocated to children of different races, through insider networks that channel employment opportunities to the relatives and friends of those who have profited most from present and past discrimination, and especially through intergenerational transfers of inherited wealth that pass on the spoils of discrimination to succeeding generations…white Americans are encouraged to invest in whiteness, to remain true to an identity that provides them with resources, power and opportunity.”

Intersectionality in application is the most effective way of approaching history to uncover and honor the multifaceted American identity. It provides us a springboard for equity and social justice. “It starts from the premise that people live multiple, layered identities derived from social relations, history and the operation of structures of power.” It is not, however, a way of combining identities to increasing one’s burden, to indicated one group is more victimized than another, but rather, “as producing substantively distinct experiences…to reveal meaningful distinctions and similarities in order to overcome distinctions” It rests on the foundation of gender relations and anti-racism; shifting away from binary thinking.

“There are no human rights without women’s rights, there are no human rights without Indigenous peoples’ rights, the rights of the disabled, of people of colour, and of gays and lesbians.” Without looking at the broader picture of economic, political, social and cultural factors then we simply cannot effectively shift to a more equitable society. By transforming the way we look at identity and history, by looking at power from the bottom-up; analyzing poverty and how it impacts groups of people at various points of time and locations we can facilitate the advancement of different groups. “Our ability to effect progressive change in the face of the fundamentalist forces, neoliberal economic policies, militarization, new technologies, entrenched patriarchy and colonialism, and new imperialism that threaten women’s rights and sustainable development today.”

Sources:

Cox, Daniel. “Beyond Economics: Fear of Cultural Displacement Pushed the White Working Class to Trump.” PPRI (May 2017). Accessed September 21,2017. https://www.ppri.org/research/white-working-class-attitudes-economy-trade-immigration-election-donald-trump/.

Tankersley, Jim. “How Trump won: The revenge of working-class whites.” The Washington Post. November 09, 2016. Accessed December 05, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/11/09/how-trump-won-the-revenge-of-working-class-whites/?utm_term=.7b362b3aad11.

Shin, Laura. “The Racial Wealth Gap: Why A Typical White Household Has 16 Times The Wealth Of A Black One.” Forbes. January 25, 2016. Accessed December 05, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/laurashin/2015/03/26/the-racial-wealth-gap-why-a-typical-white-household-has-16-times-the-wealth-of-a-black-one/#1caff2591f45.

Lipsitz, George. The possessive investment in whiteness: how white people profit from identity politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006, 158.

Symington, Alison. “Intersectionality: A Tool for Gender and Economic Justice.” Women’s Rights and Economic Change, no. No.9 (August 2004). Accessed December 02, 2017. https://lgbtq.unc.edu/sites/lgbtq.unc.edu/files/documents/intersectionality_en.pdf.

Jr., Henry Louis Gates. “How Many Slaves Landed in the US?” The Root. January 06, 2014. Accessed December 06, 2017. https://www.theroot.com/how-many-slaves-landed-in-the-us-1790873989.

Grandin, Greg. “Capitalism and Slavery.” The Nation. April 14, 2016. Accessed December 06, 2017. https://www.thenation.com/article/capitalism-and-slavery/.

Painter, Nell Irvin. The History of White People. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.34.

Kurashige, Scott. The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles. Princeton , NJ : Princeton University Press, 2008.21.

Benton-Cohen, Katherine. Borderline Americans: Racial Division and Labor War in the Arizona Borderlands. United States of America:First Harvard University Press, 2011. 27-29.

Kladzyk, René. “The Long, Violent History of Racism and Sexism at the U.S.-Mexico Border.” Teen Vogue. December 03, 2017. Accessed December 06, 2017. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/racism-sexism-violent-history-mexico-us-border.