An analysis of primary sources pertaining to Connecticut Valley Hospital and mental health treatment in the late 19th-early 20th century.

Prior to the 1840s, low-income people living with mental illness in Connecticut were held in confinement in Almshouses, charitable housing provided by the community or private benefactors. State Legislators at the time realized the necessity for the state to provide care to the disadvantaged masses. In 1840, a site in Middletown was selected to build a state hospital for the “pauper insane.” Twenty-six years later, the Connecticut General Hospital for the Insane was erected, and in 1868, they admitted their first patients.[1] Later, the name was changed to Connecticut Valley Hospital (CVH) and is still in operation to this day.

Over the summer, I began a research project examining the history of CVH and mental health policy in Connecticut in the late 19th-early 20th century. I am endeavoring to examine the intersections of incarceration, eugenic science, and their relation to ability, race, gender, and class.

As our nation attempts to re-examine carceral and mental health institutions, it is vital to investigate the roots of these systems. How did the State use CVH to exert control over marginalized groups? What are the intersections of mental health treatment and incarceration at CVH in the beginning decades of its inception? How did prominent figures at Yale, such as Robert Yerkes or Irving Fisher, influence Connecticut mental health policy and practice? The goal of my research is to raise questions about the extent to which medical institutions, policy, hereditarian ideology and people’s resistance, shaped the foundation of modern society in Connecticut.

What I have uncovered so far, illustrates how pervasive eugenic science was to the foundational principles of mental health research and practice. From forced sterilizations to discussing the ethics of executing people with mental illness, eugenics was a ubiquitous force in Connecticut’s modern history.

While this research has only just begun, I wanted to closely examine some of the sources I have uncovered. The articles featured, range from 1869 to 1921 and only offer a brief snapshot of the rich complexity of this topic. However, each one of the five sources provide us with some insight on the perspectives of early mental health treatment and policy at the time. This research will become part of a larger graduate thesis project at some point, but for now, it lives here.

“Proposal to Kill Lunatics,” The Hartford Evening Press, July 8, 1869

In this report about a proposal in England to execute the “criminally insane,” the author condemned lawmakers across the pond. They argued an execution policy facilitated all people with mental illness to face the same fate. The author doesn’t necessarily discount capital punishment for people who committed crimes, but feared sweeping generalizations would potentially cause innocent people to be criminalized. “All lunatics are liable at any moment to become criminals, and they are not amenable to the criminal law for their acts.” It begs the question, where is the line drawn between rehabilitation and punitive action? How does the state differentiate what type of mental illness is worthy of care, and which deserves capital punishment?

The author explained, the people advocating for execution, claimed it was an act of mercy. English academic journals outlined it was a false sense of compassion to keep people alive that have been deprived of everything that makes life worth living. They said because patients cannot be cured of their madness, it would be “better and wiser to put them out of the way altogether.”

In response, the author claimed New England was a far more advanced civilization as indicated by the high level of mental healthcare. In fact, the author mentioned civilization more than once in the article. “But now, in London, the very center of civilization, it is gravely recommended that all such of these poor creatures as have committed an act which would have been criminal if they had been sane shall be knocked in the head, or in some other way exterminated.” While the author took great pains to point out the ethical debate is a barbaric one, orienting New England or London as epicenters of civilization can be viewed as an expression of white supremacy.[2] Eurocentric and nationalistic notions of Western civilization have oftentimes been used as a tool for perpetuating racism and white supremacist credo.

While this article precedes Francis Galton’s 1883 study on eugenics by fourteen years, the ideology was the basis for much of the scientific community at the time. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century naturalists like Johann Blumenbach, Carl Linnaeus and François Bernier categorized people in racialized and gendered hierarchies which served as method of asserting biomedical power over individuals. According to Londa Schiebinger, “all too often hierarchies of natural worth are established- consciously or unconsciously- that mirror the faces dominating scientific communities. Objectivity in science cannot be proclaimed, it must be built.”[3] The ways people were categorized by race, gender, class, ability or criminality was built on the foundations of patriarchal white supremacy. This is evidenced by the policy proposals of the time.

The author concluded the article by asserting wealthy people were most vulnerable to this policy. They argued rich, older individuals could be committed by their next-of-kin. If they were sentenced to death, then those that committed them, reaped the benefits.[4] While there were cases of people wrongfully committed to mental institutions, it is clear the people who were the most oppressed by harmful mental health policy, were not the rich and powerful. “Inequality historically under neoliberal capitalism has been either largely ignored or underemphasized by the mainstream press or treated as part of the natural order.”[5] Rooted in African chattel slavery and genocide of Indigenous peoples, capitalism disrupts social ties and forces people to be in competition with one another; alienation is seen as inevitable. By design, it requires the “loss, disposability, and the unequal differentiation of human value.”[6] Historically, those who have been the most exploited by capitalistic greed, have not been the wealthy.

“Among 1,260 Crazy Poor The Majority of Them Women,” Hartford Times, October 12, 1884

In this rich primary source, it revealed how age, race, gender, class, and ability all converged in the halls of CVH. In 1884, women outnumbered men in the hospital by one hundred and forty-seven, there were 704 women and 557 men admitted. This disproportionate gender division could be a result of the ideology at the time, that mental illness or “hysteria,” was a women’s issue.[7]

In Londa Schiebinger’s book, Nature’s Body, she examined the gendered and racialized bias that influenced 18th century scientists and biologists. “The notion that woman-lacking male perfections of mind and body- resides nearer the beast than does man is an ancient one. Among all the organs of a woman’s body, her reproductive organs were considered most animal-like.” Schiebinger illustrates the cultural narratives that molded the foundational principles of biology and medicine, and we can observe its influence in 19th century practices and treatment of women.

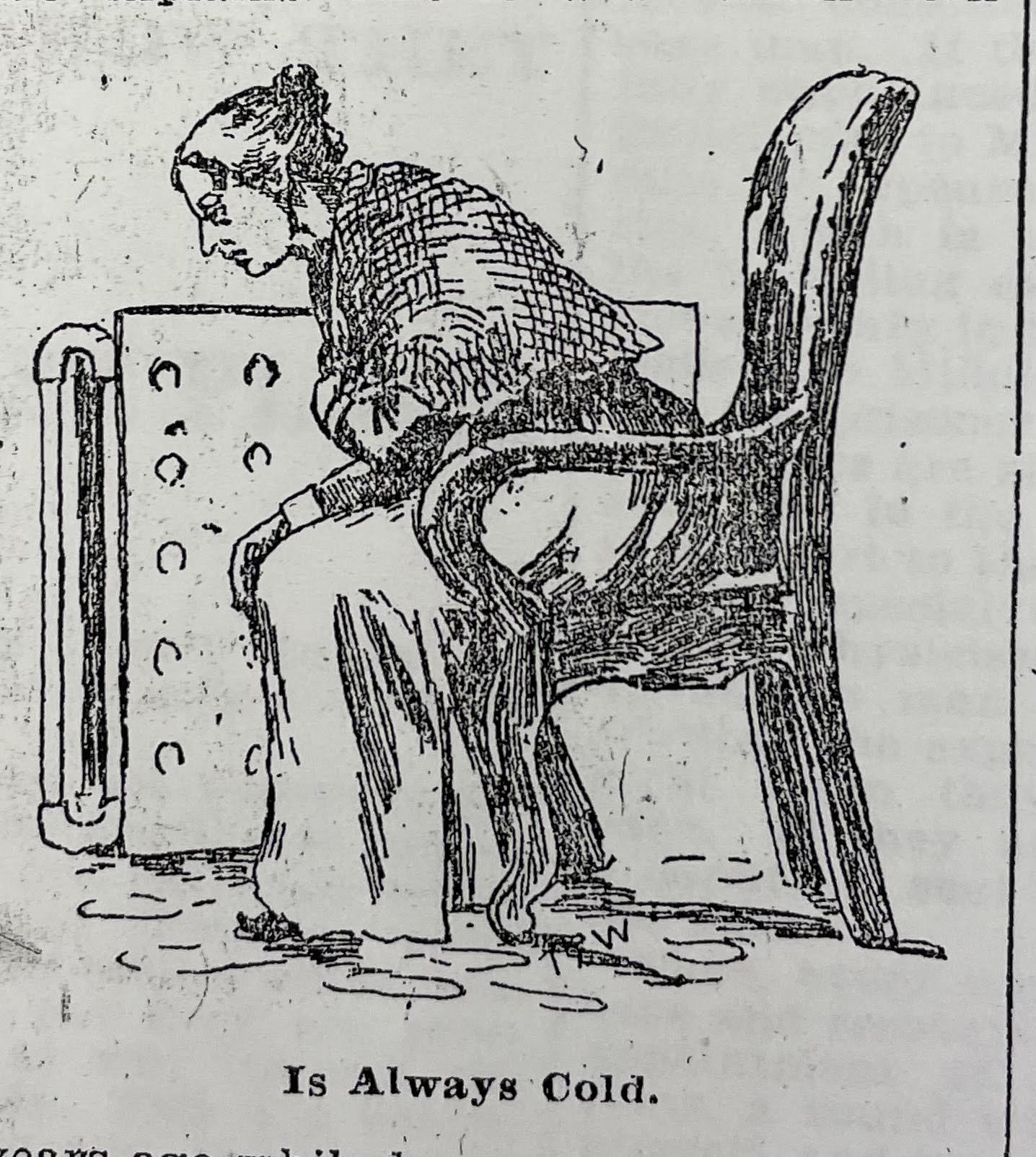

In the Hartford Times article, the author visited CVH and described the women’s conditions as wretched and forlorn. Most of the women were older, the author assumed they were former mothers and lamented as he imagined they were abandoned by their children. “Worn out physically, bent over with constant work, her mind naturally weakens by such treatment and she becomes demented. Then- the insane asylum as a pauper. Dead to herself, she never knows that her family does not want to see her.”[8] What is fascinating about this, is the writer’s choice to describe the women’s humanity from the perspective of motherhood.

This too, can be traced back to 18th century scientific perspectives, seen in Carl Linnaeus’ classification of mammals. The term Mammalia quite literally means, “of the breast.” According to Linnaeus, the female characteristic of lactation is an animalistic trait, but also one that ties humans to the natural world and therefore must be protected by reasonable men. “In sum, for eighteenth-century male naturalists, that which distinguished female humans from animals was not reason, speech, or the ability to create culture, but rather distinctive forms of sexual anatomy.”[9] The naturalist perspective that women are designed to be mothers and nurturers, coupled with the article’s lambast of older women being cast off to the state hospital, denotes societal degeneracy. As the woman deteriorates, the family structure also crumbles. As the woman is abandoned by her family, she falls into economic destitution, the broader community suffers. Centering the need to protect women on the basis of their ability to give birth, detracts from the necessity to protect their sovereign personhood.

There is also further evidence claiming diminished capacity of women’s minds in the article. The author argued there is a biological difference between genders in how they develop mental illness in the first place. They claimed that while men, driven by reason, “become demented from their own acts,” women are driven to insanity by the actions of others. This perspective denied women cognitive agency, as well as put in place the systems facilitating her denial of autonomy. It also perpetuated the stigma that men couldn’t develop mental illness from biological, environmental, or social factors; the author managed to separate masculinity from mental illness.

The rest of the article documented specific women and a couple men who resided in the hospital. While there is barely any mention of race in the first few boxes of the CVH Superintendent’s Scrapbooks archives, it is important to note this article documented a Black man who was hospitalized. His name was Fred Cook, who was initially arrested for public drunkenness and later was sent to CVH after being “found to be demented, for he claimed to be full of snakes, spirits and hob-goblins, generally.” I believe the absence of race in the CVH scrapbooks regarding mental health is noteworthy; the effort to erase Black mental health is tangible. Cook’s documented admittance in the hospital raises questions about the state’s relationship to providing mental health treatment to the Black community, where it fell short, and where it was explicitly harmful.[10]

“Escapes From Insane Asylum,” New Haven Register, November 15, 1896

“Escapes From Insane Asylum,” New Haven Register, November 15, 1896

The article, “Escapes From Insane Asylum,” documents three men identified as, Peters, Castagretti, and Hurley, who escaped from the hospital and were formerly incarcerated at the prison in Wethersfield. While the headline suggests that it was a report on the escapees, the majority of article documented the conditions and drew explicit comparisons between the hospital and the prison.

The author argued the hospital in Middletown is no place for a convicted criminal, as the surveillance and security of the institution is lower than that of the prison. They cite the latest escape as a reason to open the debate as to whether incarcerated people with mental illness should even be given treatment in Middletown in the first place. “…has brought up anew the question whether it would not be better to keep the insane convicts in Wethersfield, where they really belong, rather than to take the trouble and risk necessary to the shifting of this class of criminals from one place to another.” Dehumanizing language was used to describe incarcerated people and claimed some feign mental illness to receive temporary comforts.

The writer went on to illustrate the symbiotic relationship the hospital had with the prison. They identified approximately forty individuals who are classified as “criminally insane,” that is, someone accused of a crime and acquitted for mental incapacity. At the time, the hospital had a convict ward, which was originally designed to be a carpentry workshop. Due to overcrowding and a heightened demand to transfer incarcerated individuals to the hospital, the space was repurposed. To mimic the conditions of a prison as much as possible, the ward was fortified with bars and strengthened to prevent escape. “Specially appointed attendants have charge of the patients in the convict ward and, aside from the necessary modifications entailed by the fact that they are under treatment for insanity, the convicts are treated about the same as they would be were they still in prison.” This statement is peculiar when one considers the original intention of the hospital; to provide compassionate care for those in need.

In the concluding arguments, the author cites an upcoming General Assembly meeting as the perfect time to begin discussing a solution. The author suggests enacting a law requiring all people convicted of a crime to stay at the prison whether they were deemed insane or not. They framed it as an economic solution to have an insanity ward within the prison and transfer them when they exhibited signs of illness.[11]

According to Dr. Daniel HoSang, there is a direct connection between incarceration and medical care. There are overlapping forms of control, as a hospital has the power to assert domination over people’s bodies. This is like the state-sponsored violence found in prisons, as people are forced to surrender their autonomy.[12] In the 1896 New Haven Register article, we see the unmistakable ways mental health treatment was directly connected to incarceration in the state.

An Act Concerning Operations for the Prevention of Procreation, Department of Mental Health Records, 1909.

This primary source was a 1909 law documented in an archive labelled, Laws of Connecticut Affecting Insane Persons. It was one of the first sterilization laws in the country, second only to Indiana. It wasn’t until the 1920’s that the law was fully carried out. Between 1909 and 1963, approximately 557 people were sterilized, 92% were women. 74% were identified as mentally ill and 26% were considered “mentally deficient.”[13]

This law was outlined to only be applicable to people being held in state prisons, the hospital for the insane in Middletown, and Norwich state hospital. In a 1919 amendment, the law expanded to encompass Mansfield State Training School and Hospital at Mansfield Depot. The law states, “procreation by any such person would produce children with an inherited tendency to crime, insanity, feeble-mindedness, idiocy, or imbecility, and there is no probability that the condition of any such person so examined will improve to such an extent as to render procreation by any such person advisable… then said board shall appoint one of its members to perform an operation of vasectomy or oophorectomy…”[14] This law reveals how eugenic science was taking hold in Connecticut.

Dr. Henry M. Knight and his son, Dr. George H. Knight were major proponents in getting the law passed. Henry founded the Connecticut School for Imbeciles in 1858, and George, believed people with developmental disabilities should be segregated and confined from the masses. Not only was he a major figure in the 1909 sterilization law, but he also helped to pass a law prohibiting the “feeble-minded” from marriage.[15]

In addition to Henry and George Knight, Yale University was also the site of eugenic ideology. In 1926, the American Eugenics Society and The Race Betterment Foundation were founded by Irving Fisher, an economics professor at Yale. In addition to Fisher, Robert Yerkes was a professor in psychobiology, and created mass aptitude testing. The tests ventured to measure cognitive capacity and moral standing. These mass tests were used to justify forced sterilizations, control the flow of migrants and immigrants, as well as college admissions in the form of standardized testing.[16] While the sterilization law was overturned in 1965 with Griswold v. Connecticut case, the legacy of eugenics has had lasting effects on the modern society.

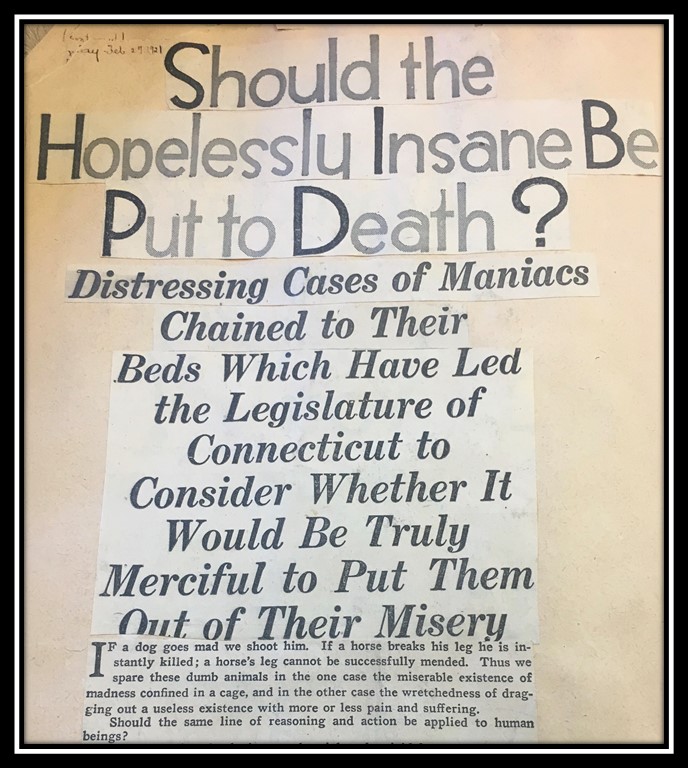

“Should the Hopelessly Insane Be Put to Death?,” Feb. 27, 1921

Fifty-two years after the debate in England, over whether to execute the mentally ill, the topic was revisited once again in Connecticut. This time, it was not met with the same level of condemnation as before. Eugenics was gripping the nation as a dominant ideology. Consequently, Connecticut lawmakers genuinely debated whether it was merciful or not to execute low-income people living with mental illness.

In this column, a committee of State Legislators visited Norwich State Hospital. Dr. Franklin Wilcox, the superintendent of the hospital, gave them a tour. After seeing the conditions, they raised the question whether it was more ethical to execute people, rather than attempt to provide care.

“If a dog goes mad we shoot him. If a horse breaks his leg he is instantly killed; a horse’s leg cannot be successfully mended. Thus we spare these dumb animals in the one case the miserable existence of madness confined in a cage, and in the other case the wretchedness of dragging out a useless existence with more or less pain and suffering. Should the same line of reasoning and action be applied to human beings?”

The lawmakers pressed through the door of a small, padded cell where they observed a man strapped to the bed. It was then that one of the lawmakers exclaimed, “I would rather be dead than lead such an existence.” Another added, “Certainly death would be preferable.” This opened a dialogue surrounding the ethics of execution and if it was a humanitarian effort. “What we have seen here to-day raises the question in my mind if we ought not to present a bill to the Legislature providing that the hopelessly insane may be lawfully put out of existence.” Following that, they discussed implementing safeguards to protect those that have a chance of being cured from their illness.

To defend the lawmaker’s argument, the author cites the Bible as a justification. They state the commandment is “Thou shalt not kill,” and quote Bible scholars’ interpretation to mean, “Thou shalt not commit murder.” The author went on to say the Christian scripture was used countless times in the past to justify the death penalty.

The exposé documented various patients’ diagnosis and characteristics at Norwich, with salacious detail. While intended to grip the reader with a sense of pity and compassion for the individuals described, from a modern-day lens, it’s gratuitous and exploitative.

“Night and day their screams ring in her ears and her poor, shattered mind pictures them beaten and starved and shockingly abused. She calls aloud for help, appeals to anyone she may see to save them, and when her crying has exhausted her, sinks into a moaning, gasping, troubled sleep. Not a thought for herself. She seems to have forgotten her own existence; a striking example of the maternal instinct surviving the wreck of all else that was human in her.”

After describing multiple accounts of mournful cases, the author asserted if one spends enough time with a person who is mentally ill, they too will develop some sort of insanity, that mental illness is a communicable disease. As medical historian Alexandra Minna Stern outlines, eugenic ideology was always linked to fears of biological degeneracy and efforts towards genetic purification.[16]

While many were in agreement, this proposal was not unanimous among the legislative committee. Lawmakers like Senator Edward F. Hall and the chairman Representative Robert O. Eaton both agreed the action was humane, however posed it as impractical because it went against the values of Christianity. Senator Charles M. Bakewell, the head of the philosophy and psychology department at Yale said, “Put human nature being what it is, and human knowledge being what it is, I for one should not like to vest such power in any individual or group. I will say, however, that it is not a matter unworthy of consideration, for it is a revolutionary proposal, a proposal to take life for the benefit of the killed rather than the killer.” Bakewell was onto something, even if he wasn’t completely against hearing out the argument. He posed the philosophical dilemma which arose with eugenics; he saw the potential for abuse and how authoritarian politics could facilitate genocide.

Emily Sophie Brown, member of the House of the Committee of Humane Institutions was the loudest in disagreement of this proposal. She posed the questions; how can one truly know someone is “hopelessly insane?” And if there was a quantifiable way to measure that, how does one fully know the extent of their suffering? Brown also pointed out that the proposal does not address the heart of matter which is providing adequate care. Lastly, she highlighted the timeline of mental health practice and rightfully asserted, there’s so much more to learn about the human mind. “Not more than a hundred years ago in this very land insane people were beaten to drive the devils out of them; witches, who might have been a little queer, were burned; and up to Civil War times very little effort was made to cure insanity…Which proves to me that the study of the mind is in its infancy, and that if we only persist we shall sometime know so much about diseases of the mind that we would no more think of executing an insane person that we would of killing a sufferer from adenoids.”

Ultimately, this proposal did not come to fruition, but it didn’t have to for eugenics to remain embedded in social and economic systems in the United States for generations to come. Forced sterilizations persisted nation-wide into the mid-20th century, and possibly into today. Within the last year, whistleblower reports emerged documenting women being sterilized at prison camps along the U.S.-Mexico border.[17] While fascist doctrine has become a commanding political force once more, it’s important to remember that all along, there have been voices of dissent. When asked what he thought about the proposal to execute the mentally ill, Reverend John G. Murray, a Connecticut Roman Catholic bishop said, “Think? I shouldn’t have to take a minute to tell you what I think, and you shouldn’t have to ask me to know what I think.”[18]