There is a lot of documented history analyzing enslaved people’s marriages and forced separations but there is very little mention of divorce.

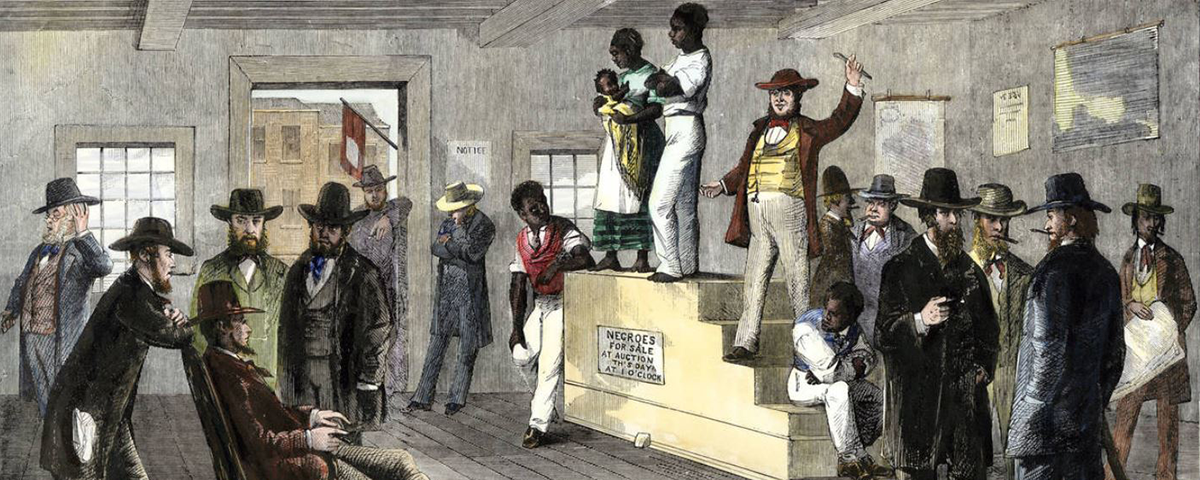

There are many misconceptions in American history regarding its slavery past. One common misconception is that slavery was a Southern problem, which cannot be further from the truth. In fact, Connecticut began importing African slaves in 1638 and their economy was heavily reliant on slave trade. According to Armani White, “The Connecticut River was one of the first sites of slavery in the North. After the Pequot Wars of 1638, in which European colonial forces massacred Indigenous Pequot natives, the surviving Pequots were enslaved and shipped to Bermuda in exchange for African slaves. These bartered African slaves were the first of their kind in New England.” And while New England’s geography and climate was such that it didn’t demand a high volume of farm labor, Connecticut had the highest number of slaves in the New England region. Additionally, insurance companies in Connecticut provided services to slaveholders to insure their investment in human trafficking, New London built slave ships and later, Connecticut cotton mills heavily relied on Southern cotton plantations and slave labor for production.

With that said, this article will examine enslavement in Connecticut and in particular, a petition for divorce. There is a lot of documented history analyzing enslaved people’s marriages and forced separation but there is very little mention of divorce. In Tyler Parry’s Enslaved People and Divorce in the African diaspora, “If slaves ever separated, it was a forced split caused by the master’s interference. Former slaves naturally preferred to disclose how enslaved people fought for marital dignity to critique the hypocrisy of “Christian” slaveholders who severed their marriages.” Abolitionists also turned away from mentioning some enslaved people willingly walked away from their partners, viewing it as fuel for racist whites that believed people of African descent didn’t respect Eurocentric matrimony.

Historians of the 1970s and 1980s wanted to move away from prior historical narratives that described slaves as “docile and cultureless,” and instead documented the familial bonds as a method of resistance. They revealed that enslaved people, against all odds, formed domestic structures despite white slaveholding. “The narrative of resistance proved immensely popular, some viewed the slave family as a unit fostering psychological survival.” Modern historians studying slavery and capitalism, caution from romanticizing slave communities, citing thousands of examples of forced separation as evidence. However, it’s vital to cite moments where enslaved people claimed their agency. “Like any other group, enslaved people acted upon their feelings and passions. Willingly severing their marital tie was one way to express dissatisfaction with a partner and dictate the terms of enslaved people’s relationships.” While divorce is not the dominant narrative, it’s worth mentioning that it did occur.

Divorce was not a foreign concept in the Atlantic African region. Most West African nations had a cultural set of rules when severing marital relationships, which favored the woman. Courtship traditions included a man bringing gifts to the woman’s family. “Often called a bridewealth, the bride’s parents retained the value of the husband’s original gift in case the partners were dissatisfied with each other. If the woman decided to separate from her spouse, she returned to her family, and the wife or her family reimbursed the husband the value of his gifts. This process ended the marriage.” This process was obviously hard to replicate under slavery. In any case, as we begin a process of deromanticization, we must properly contextualize historical figures and resist portraying them in the way we want them to be. Parry points out, “to accurately reveal how enslaved people viewed their romantic attachments we must examine how and why they willingly separated from one another.”

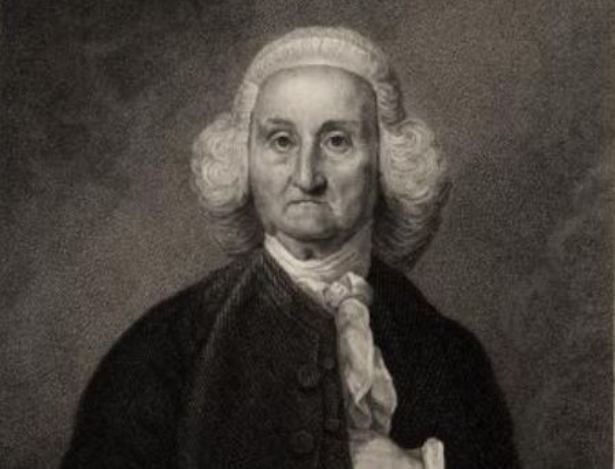

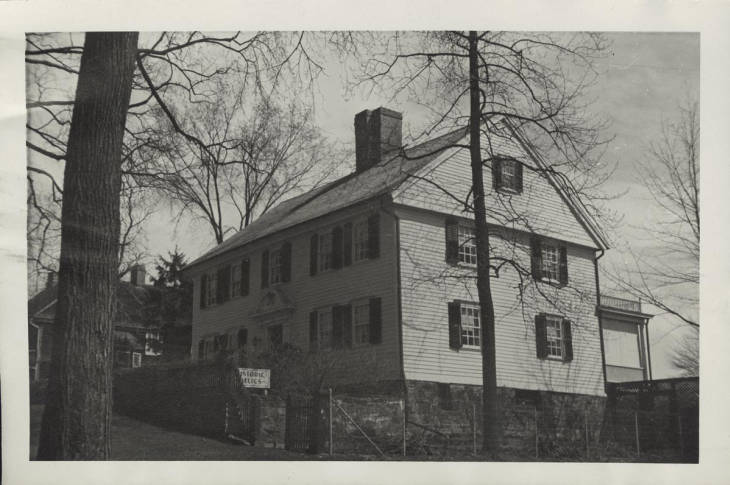

The earliest known case of a divorce involving African Americans in Connecticut is from March 1771, James v. Grace. The petition for divorce was filed by James, a slave of Abigail Hyde of Norwich, from Grace, a mixed race servant of Johnathan Trumbull of Lebanon, on the grounds of desertion. Jonathan Trumbull was a merchant and politician and one of Connecticut’s most famous governors. During the Revolutionary War, Trumbull was the only governor to side with the colonists. He was also the last governor of the Connecticut colony and the first governor of the state of Connecticut. Less is known about the slaveholder, Abigail Hyde, she was the widow of Captain Daniel Hyde and she died a year after the divorce proceedings.

Before I delve into the details of the divorce case, it’s important to note the conditions of slaves and servants in Connecticut. Again, because the climate and geography of Connecticut yielded a short growing season, there weren’t large plantations and no need for mass labor. This meant many enslaved people lived in isolation, housed in unheated attics and basements, outbuildings and barns. “They often slept on the floor, wrapped in coarse blankets. They lived under a harsh system of Black codes that controlled their movements, prohibited their education and limited their social contacts. The two defining assumptions of all the codes were that Blacks were dangerous in groups and that they were, at a basic human level, inferior.” In 1758, Jonathan Trumbull enforced these Black codes as evidenced when he sentenced three slaves, Cato, Newport and Adam, to be publicly whipped, charged them with ‘nightwalking’ after 9 pm, without an order from their masters.

James’ Petition:

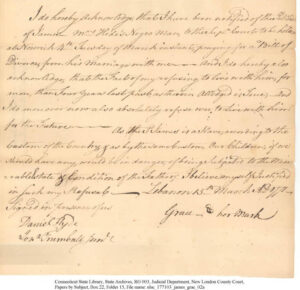

It’s clear after examining the signatures of both James and Grace, they did not write their statements. But according to the petition written on James’ behalf, he and Grace were married on November 14, 1760. The statement claims that around the month of February 1767, Grace left James and deserted the marriage. This means the petition for divorce was written four years after her purported desertion. “…being more than Four Years, Absent herself from Your Petitioner, & Willfully ___ & totally neglects her Duties, inncumbent [sic] on her, by her Covenants _____ And notwithstanding all proper arguments given _______, used by your Petitioner, to induce her to adhere to, & live in the discharge of her Duty she still doth absolutely Neglects and & Refuse a compliance thereinwith…” The petition claims Grace abandoned her duties as a wife and broke her vow. As a result, James asked for the court to dissolve the covenant.

Grace’s Deposition:

Grace’s deposition illuminates the heart of the issue and why she left him. She argues that because she’s a free woman and James is a slave, if she were to have children with him, they would be born slaves.

…the facts of my refusing to live with him, for more than four years last past, as therein alleged is True; and I do moreover now also absolutely refuse ever to Live with him for the Future- as the [sic] James is a slave, according to the Custom of the Country, of as by the same custom, our children, if we should have any, would be in danger, of being Subjected to the Mire= rabled [sic] fate of my condition of the Father; I believe myself Justified in Such my Refusal.”

This raises some questions. Did she become free after her marriage? If she was previously enslaved, when did she become free? If she was previously enslaved, how did she gain her freedom? Gradual emancipation, which stated that enslaved people became free after the age of 28, didn’t pass in Connecticut until 1784 (and people found ways to loophole that law, anyway). Jonathan Trumbull’s deposition fills in some gaps, but not all of them.

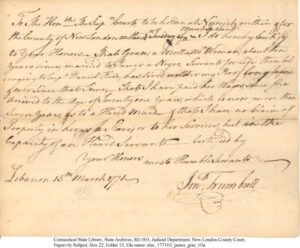

Jonathan Trumbull’s Deposition:

According to Trumbull, he certifies that Grace had been married to James for about 10 years or so and that she had lived under his roof the whole time. He also states that he payed her wages since she was 21, which was seven years prior. Lastly, he said that she’s a hired maid and has no claim of property in her as a slave or to her services, rather, she is a hired servant. This doesn’t say, with clarity, that she was enslaved prior to turning 21, but it does show that Grace was married to James when she was 17, separated when she was 24, at the time of the divorce proceedings, she was 28. This also raises the question whether James ever lived on Trumbull’s estate. If Grace has always lived on his property, and she left James in 1767, did James live there for the first seven years of their marriage? The answer to this question is unclear.

Conclusions:

While there are many holes in this story, there are some conclusions we can draw from these documents. While Grace and James were not forcefully separated at an auction, slavery still separated their marriage. Grace didn’t want to have children with James, only to see them sold to slavery. She was able to gain her freedom, while James did not. Did being mixed race play a part in her freedom? Was she ever a slave to begin with? As of now, I don’t know if any other documents exist regarding James or Grace to provide us clarity. What this does reveal, however, is that servants and enslaved people did get married in Connecticut. And if it wasn’t for slavery, it wouldn’t have forced Grace to make the difficult decision to leave James. It reveals how pervasive and oppressive slavery was for both the free and enslaved.

Sources:

Connecticut State Library. State Archives. RG 003. Judicial Department. New London County Court. Papers by Subject, Box 22, Folder 15. File name: nlsc_177103_james_grac_03a. http://cslib.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p128501coll7/id/74.

Parry, Tyler. “Enslaved People and Divorce in the African Diaspora.” Black Perspectives. African American Intellectual Historical Society, March 31, 2018. https://www.aaihs.org/enslaved-people-and-divorce-in-the-african-diaspora/.

White, Armani. “The History of Slavery in Middletown.” Omeka RSS. Wesleyan University . Accessed May 16, 2020. https://wesomeka.wesleyan.edu/runawayct/the-history-of-slavery-in-middletown#five.