An analysis of the devastation of the Spanish Flu on Eastern European immigrants in Connecticut.

The Spanish Flu has probably received more attention in the past month than it did in the last hundred years. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic currently killing thousands and halting the global economy, people are looking to the past to try to make sense of this nightmare. I remember coming across the Spanish Flu when I was doing my research on the typhus outbreak in El Paso in 1917. It seemed that El Paso officials overlooked the flu outbreak at Fort Bliss because they were so fixated on their quarantine stations at the U.S.-Mexico border. I hadn’t known much about it besides that it killed anywhere between 20-100 million people worldwide and 550,00 in the U.S.

Much like everyone else practicing physical distancing while the state is under lock down, I had to find new ways to exercise instead of going to the gym. So to alleviate that, I run through a nearby Catholic cemetery. There was one particular grave that caught my eye because the perimeter of it was surrounded by purple flowers, so I decided to take a closer look.

His name was Gaetano Fallo, the headstone was in Italian. He was born in 1882 and died October 14, 1918, he was 36 years old. I assumed based on the date of his death and his age that he likely died from the flu. I looked him up in the 1910 census data and it stated he immigrated to the U.S. in 1903, was married to Rosaria Fallo and had one child, Lucia Fallo. He worked as a silk weaver, could not read or write and lived with 15 other people in a boarding house.

Gaetano Fallo’s story is significant because according to Alan Kraut with the National Institute of Health, Southern and Eastern European immigrants were significantly affected by the H1N1 pandemic of 1918. In Kraut’s essay, “Immigration, Ethnicity and the Pandemic,” approximately 23.5 million people immigrated to the U.S. between 1880-1920s, mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe but also from China, Japan, Canada and Mexico. While immigration slowed during WWI, it remains as one of the largest waves of immigration in U.S. history. American nativists responded to this mass influx of immigration negatively.

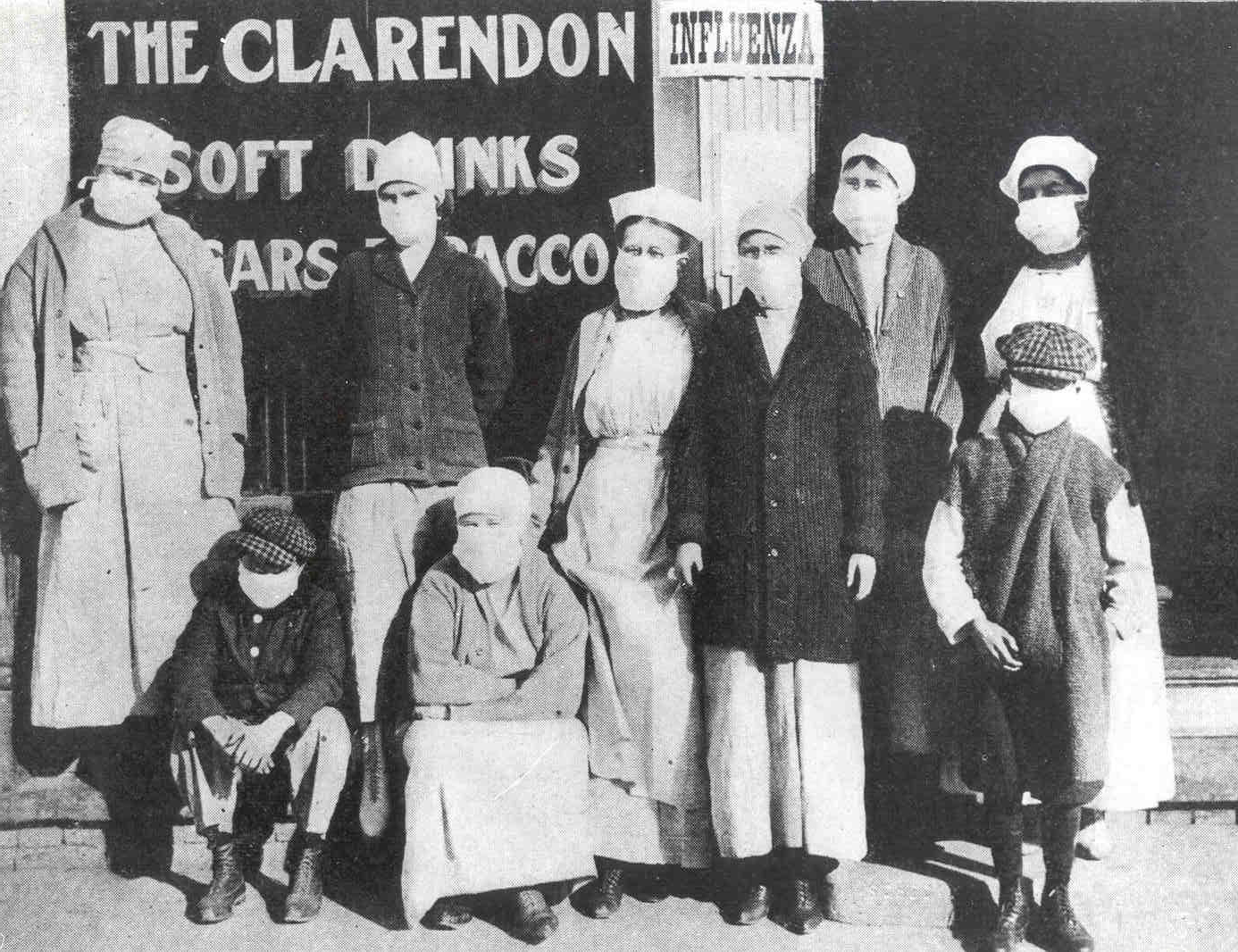

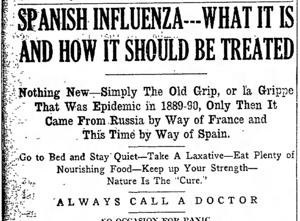

Americans were fearful of the disease and their view that “the grip” came from abroad, justified their rationale for exacerbating their preexisting prejudice. People speculated the epidemic was spread by Italians as they have a custom of kissing the dead as an expression of grief and respect for the departed. One public health official stated, “The foreign element gives us much trouble when an epidemic occurs. They pay no attention to the rules or orders issued by the health department in its efforts to check the disease.”

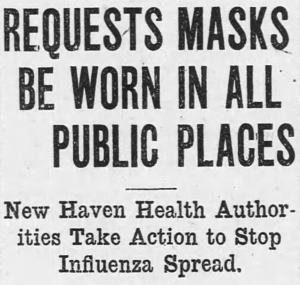

It was true there was a challenge of communication for public health and government personnel to give health and safety guidelines and regulations. They turned to foreign-born physicians, community leaders like churches and foreign-language press as mediators. Italian newspapers discouraged kissing as a common greeting.

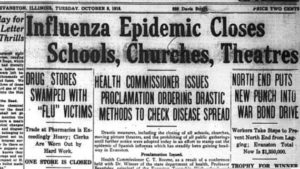

Because influenza was not classified as a reportable disease by the U.S. Public Health Service in 1918, the data tracking the rate of infection was spotty (sound familiar?). Connecticut was hit particularly hard so they tracked the rate of infection very well compared to the rest of the country. An estimated 8,500 people died in Connecticut from the Spanish flu. A study done in Hartford concluded that Southern and Eastern European immigrants from Italy, Greece and Poland were major carriers of disease. The data showed new immigrants had a notably higher death rate than native-born Americans. So while Americans blamed Italians for the spread of the disease, they were in fact, the most vulnerable to infection.

There were some possible reasons for Southern and Eastern European immigrants having a higher rate of infection. Most came from agricultural communities in small, remote villages where the chances of exposure to influenza earlier in their lives would have been small so they didn’t develop any sort of immunity. There was also the poverty of immigrant life; they worked long hours, had congested living conditions in tenements and experienced malnutrition.

While American nativists blamed Southern and Eastern European immigrants, the primary way the disease entered the state was at the New London Navy base as WWI hastened the rate of infection. The first reported case was September 11, the same week Babe Ruth came to Hartford to pitch at a baseball game. Thousands poured into the stadium to catch a glimpse of the famous player. A month later, tens of thousands would fall ill and thousands would perish. Click on the graphs below for more information.

Again, I’m writing this in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. There are many clear parallels between the two outbreaks; the most vulnerable populations continue to be most susceptible to disease. Today, Black and Latinx people, homeless populations, incarcerated people in prisons and ICE detention camps, immunocompromised, elderly and essential workers are the most susceptible to infection. As of now, in Connecticut, there are 27,700 confirmed COVID cases and 2,257 dead. I’m sure as you read this, the numbers will be different. I’m also sure that the number of actual cases is probably 10 times higher than recorded. While we have significant advancement in medical technology, medicine, protective equipment and sanitizers (shout out to Lupe Hernández, a Latina nurse who invented hand sanitizer in 1966), we find ourselves just as little equipped to deal with a public health emergency as we were in 1918. We could blame our ineffectual leadership, a patchwork response, the President downplaying the disease for months until it was too late and then later encouraging people to go back to work… there will be plenty of time to blame as we hope for a solution. What is clear, however, is our nation’s imbalance; systemic health and wealth disparities are exacerbated in a public health emergency.

Sources:

Amore, Dom, “In 1918, as a pandemic ripped through Hartford, Babe Ruth drew big crowds at the worst possible time,” Hartford Courant, April 9, 2020, https://www.courant.com/sports/baseball/hc-sp-baseball-babe-ruth-spanish-flu-20200409-20200409-uz3ee3epyrem7nm5rth7st5p3q-story.html.

Arcari, Ralph D., and Hudson Birden. “The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in Connecticut.” Connecticut History Review 38, no. 1 (1997): 28-43. Accessed April 30, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/44369461.

Year: 1910; Census Place: Middletown, Middlesex, Connecticut; Roll: T624_136; Page: 13B; Enumeration District: 0307; FHL microfilm: 1374149.

Kraut, Alan M. “Immigration, ethnicity, and the pandemic.” Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974) vol. 125 Suppl 3,Suppl 3 (2010): 123-33. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S315.