The eugenics movement emerged in the late 1880s and dominated the field of science until Nazi Germany exposed the ways in which the movement could be used to justify atrocities. As a result, eugenics began to lose its credibility with the masses and diminished its legitimacy as a science in the years leading up to World War II. Its remnants, however, prevailed throughout the twentieth century and consequently into the modern era of healthcare.

As a result, LGBTQ+ people in the mid-twentieth century remained especially vulnerable to oppressive tactics such as institutionalization, incarceration, forced medication, and sterilization. Major proponents of eugenics were concerned with regulating sexual behavior and gender identity towards normative practices defined by a white, cisgender hetero-patriarchy.[1] Breakthrough disruptive research like Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male permanently shifted the field of psychiatry in 1948, but homosexuality and transgender identity were still associated with personality disorders and maladjustment in the 1950s and 60s in the state of Connecticut.[2]

Despite that, LGBTQ+ people vigilantly challenged this dominant narrative of pathologization to create a visible, thriving community in the state. Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people were not merely compliant bystanders of early science; through their own research and activism, they shifted the definitions of “normal,” both intellectually and spatially which forged a path towards human rights. Traditional frameworks were challenged by newly adopted – and adapted – scientific methodology; counseling services, advocacy for homosexual and transgender dignity, and the act of claiming public space deconstructed social norms and defied oppressive ideologies.

Connecticut is an important site for this inquiry as it was both the location of early eugenics rhetoric as well as the site of strong anti-eugenics opposition in the form of LGBTQ+ movements throughout the mid-twentieth century. It is essential when examining the history of eugenics to document the communities of people whose very existence was in direct opposition to bigotry. Creation of a resistance culture is centered on celebrating people’s strengths, abilities and practices. Anti-eugenics demands the creation of a new space and cultivates an alternative set of values than those practiced by institutions. These contrasting spaces have an influence on pre-existing systems and encourage a larger transformation of policies and practice.

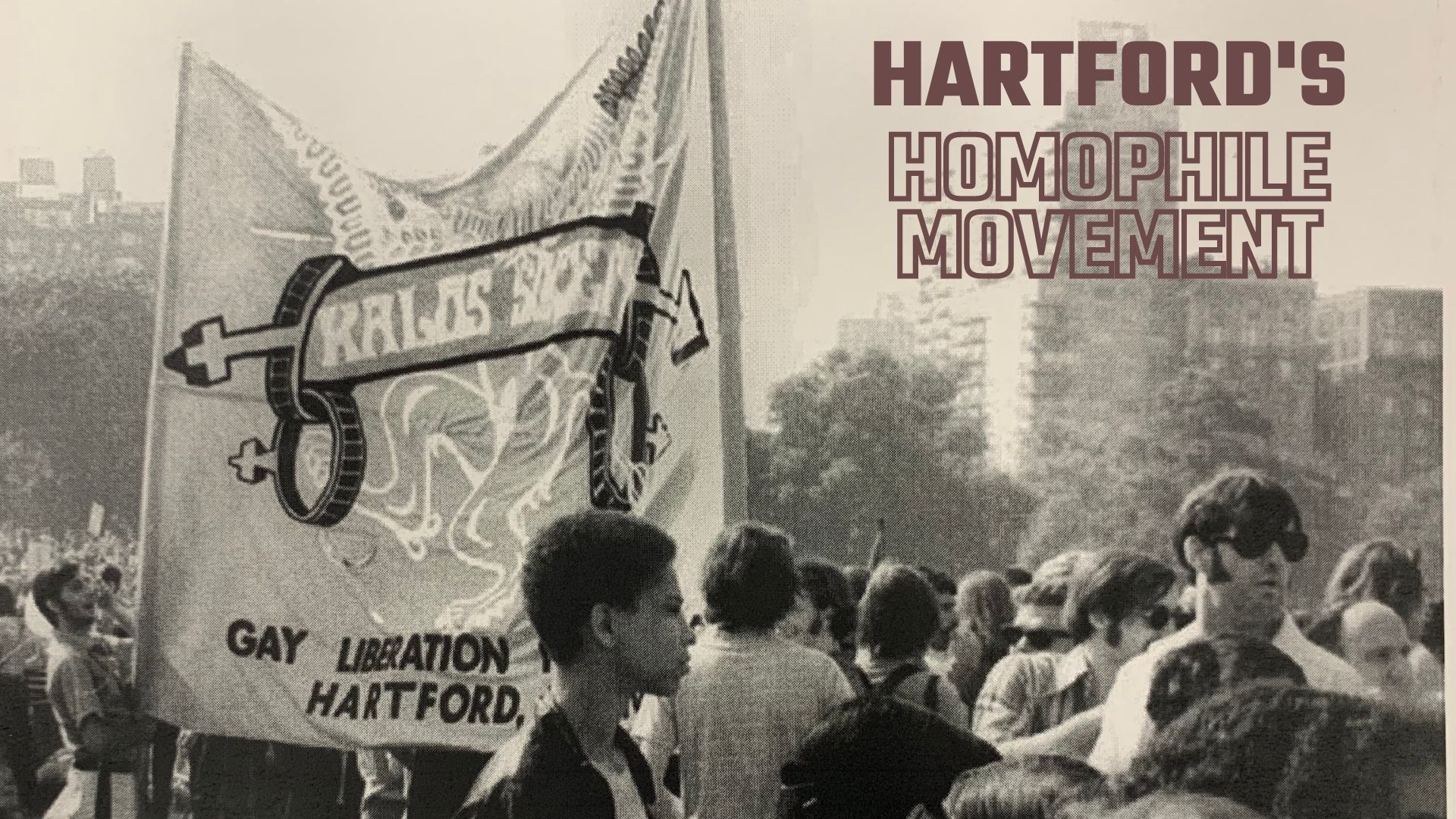

This research examines early pioneers of counseling and care like Canon Clinton Jones; psychologist and professor George Higgins; leaders of the homophile movement like Foster Gunnison Jr., who directly challenged eugenics-based treatment and planted the seeds for revolutionary action. Additionally, an inquiry of Connecticut-based organizations like The Kalos Society, Gay Spirit Radio, and Heartroots Feminist Therapy Collective, who used both physical and non-physical space as sites of transformation to formulate a visible queer community in the state. Through the analysis of stories told by gay and trans elders; archival research and oral history interviews, we may better understand the dominant forces that continue to undermine our very notions of self, community, and democracy.

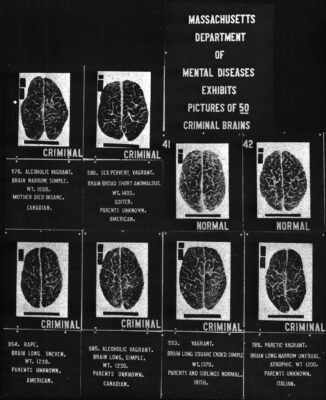

As early as 1890, physicians began to categorize and connect sexuality with race and criminality. A Chicago surgeon named G. Frank Lydstron once asserted that the causes of vice and crime were “defective physique and imperfectly developed intellect, hereditary or congenital.”[3] Throughout his career, he made the argument that racial and civil pestilence was causing America’s “social body” to ail. Like Lydstron, there was a dominant belief among scientists that aggressive hypersexuality was a common feature of the Black race. As rapid industrialization, migration and immigration transformed regions spatially and socially; scientists believed the physical body of white people was “undermined by racial and social contagions, America’s social body was ailing.” To combat this perceived social ailment, men like Lydstron traveled and lectured on various topics including sex education for children, the dangers of masturbation, venereal disease, immigration, sexual crime, lynching, miscegenation, homosexuality, and hermaphroditism.

By the turn of the century, white scientists bolstered their claims of racial difference and sexual hierarchy. They believed that the “lower races deviated from white norms of gender roles, reproductive anatomy and sexual behavior.” To them, homosexuality and “inversion” among whites threatened white manhood and the white race as a whole. Inversion was the term used at the time to describe transgender identity, with historians noting that the terminology used to describe gender and homosexuality were fundamentally racial categories from the start.

According to Melissa N. Stein, Black homosexuality was categorized with vice and degeneracy. Whereas for whites, it was seen as a symptom of pathology or congenital disease, attributed to “over-civilization.” While medical scientists believed homosexuality could be observed in any race, they viewed homosexuality in Black men as emblematic of general hyper-sexuality and an expression of an overall debased racial category. According to Stein, “sexually and gender-variant whites on the other hand were acting contrary to the norms of their race as well as imperiling it, and sexologists were far more likely to categorize them with sexual terms-such as invert or homosexual- that set them aside for other whites.”[4]

As a result, scientists cared much more about homosexuality among whites because of its implications for white supremacy and Western civilization; essentially, they saw white homosexuality as race suicide. Homosexual women were also seen as a threat to middle-class manhood by “usurping male privileges of employment, social deportment, and sexual domination over women.” Scrutinizing their bodies, doctors and scientists would point to square jaws and broad foreheads as biological markers of female deviance.

Like criminality, poverty, insanity, and intellectual disabilities, homosexuality was seen as a “hereditary taint,” passed on from generation to generation. Eugenic sexologists speculated whether civilization had become too advanced; that modernization and industrialization were creating new disorders which weakened individuals morally and physically. They believed the advancement of modern society made men more effeminate and women more masculine, and for non-whites, it was indicative of degraded morality and vice, not disease.

They did not perceive homosexuality among Black people to be particularly noteworthy, nor did they think it was a category of behavior or pathology because medical scientists viewed Black sexuality in general as inherently degraded and aimless. “The same sexologists also rarely used the term homosexual or invert to describe them, instead referencing them by names- “complexion pervert,” for example- that emphasized their racial difference and proclivity for interracial sex, the true source of their classification as perverts.”[5] This may explain why there are limited examples of Black queer mental health services in Connecticut until the 1980s. LGBTQ+ people of color often fell victim to the carceral system, another form of social isolation and warehousing.

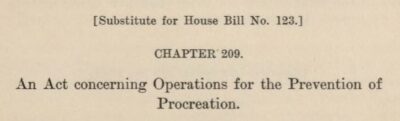

Yale University was an important site for providing intellectual validity for the eugenics movement, as it was home of The American Eugenics Society (AES). Established in 1926 and located at 185 Chapel Street in New Haven, AES was the brainchild of Madison Grant, Harry H. Laughlin, Henry F. Osborn, and Irving Fisher. Its goals were primarily to promote and codify eugenics and education programs to indoctrinate the U.S. public. AES described eugenics as “the study of improving the genetic composition of humans through controlled reproduction of different races and classes of people.”[6] In 1931, AES published a pamphlet entitled “Organized Eugenics.” The booklet promoted legislation in Connecticut relating to the “segregation of certain socially inadequate persons,” and eugenic sterilizations for people they designated “hopelessly unfit.”

People with hereditary mental illness, developmental disabilities, and epilepsy fell on that list. They also supported laws relating to marriage, contraceptive information, and federal immigration restriction. Using Biblical verses to justify their reasoning, they cite Matthew 7:18: “A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit.” Using people’s genealogical history against them, AES devised a system for measuring human social fitness by using race and ethnicity, IQ, citizenship status and family health history as metrics. They emphasized the purpose and mission of eugenics as being “concerned with the influences which affect the unborn, hereditary quality of the population.”[7]

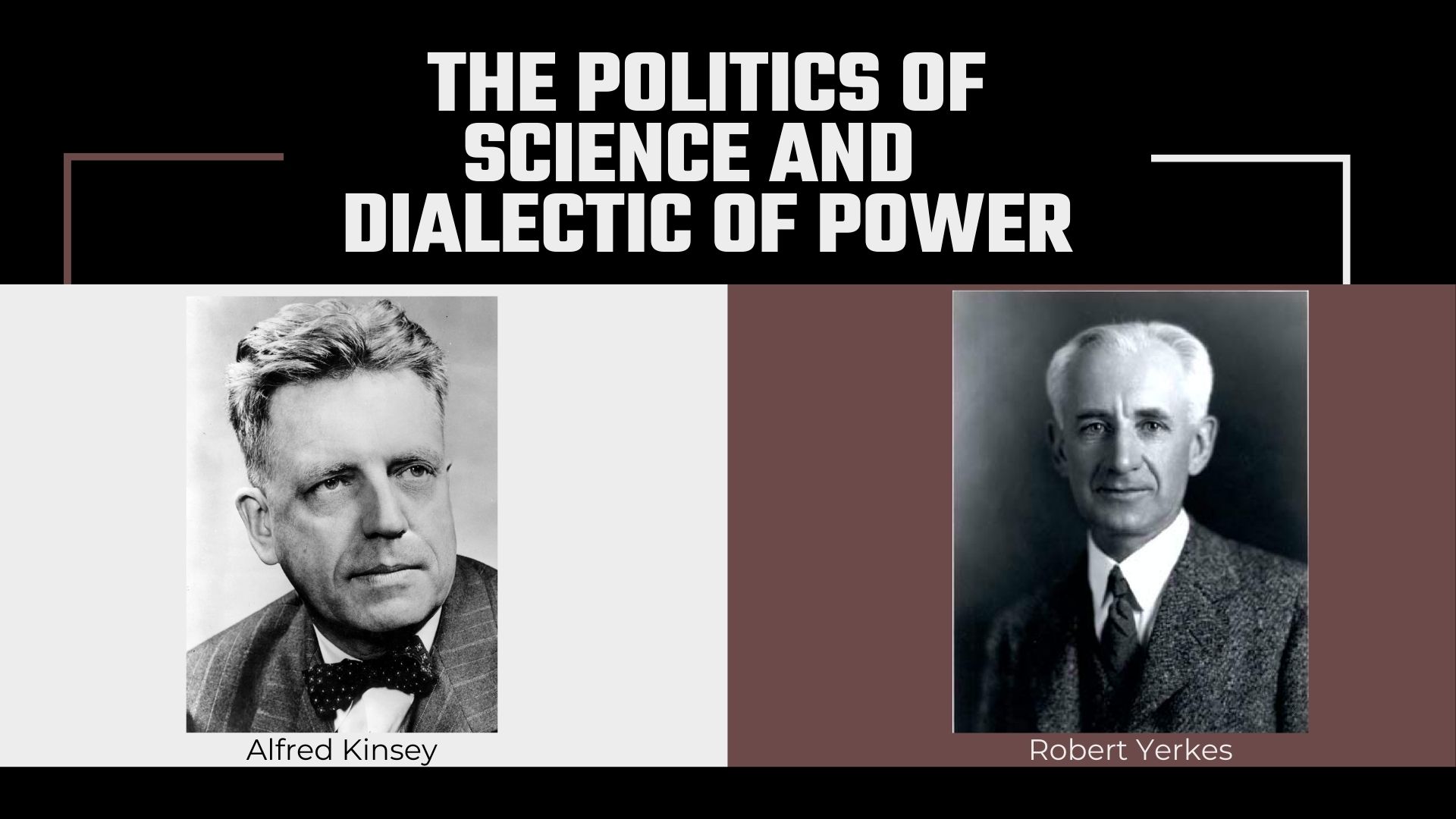

Robert Yerkes was a Yale professor who was a member of the American Eugenics Society and influential to the history of sexuality in a unique way. Yerkes was a professor in psychobiology, and credited for creating the first mass-aptitude testing. Known as The Army Intelligence Tests, they ventured to measure cognitive capacity and moral standing among soldiers during World War I. These mass tests were then deployed into schools, hospitals, and later used to justify forced sterilizations, controlling the flow of immigrants, as well as constrict college admissions in the form of standardized testing.[8]

In addition to his work at Yale and The American Eugenics Society, Yerkes was also the Chairman of The National Research Council, which funded scientific and medical research, advanced policy, and shaped public opinion.[9] This is significant because in partnership with The Rockefeller Foundation, The National Research Council funded Alfred Kinsey’s research. Kinsey was a biologist and sexologist, who founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University and gained notoriety for designing the Kinsey Scale. Also known as the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale, the Kinsey Scale was a visual model used to describe the range of a person’s sexuality at a certain time.[10]

Since 1940, the National Research Council and the Medical Division of the Rockefeller Foundation provided financial support as well as intellectual validity and political protection for Kinsey and his researchers. In 1940, the NRC only approved a grant for $1600, but by 1947, they received $46,000. Rockefeller and NRC’s endorsement of this research was critical. Each year, Kinsey received more and more funding. By 1948, Kinsey requested $40,000 of grant funding, which was over half of the total amount requested by all grant applicants.

At the Committee Meeting for Research on Problems of Sex, Kinsey spoke to board members and stated, “It was inevitable that there should be persons who were so emotionally disturbed that they have reached with some violence against us.” Kinsey thanked the organizations for all their assistance, and wanted a member from NRC or Rockefeller named as one of the trustees of the Institute for Sex Research to serve as a front-facing role to the general public, but they declined. While they had no problem funding and supporting the Institute for Sex Research, they wanted to maintain an arm’s length to controversy.[11]

In 1948, intellectual space began to transform, marking it a crucial time in medical history. It was the year that Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male was published, and the year that Robert Yerkes stepped down as the Chairman of the National Research Council. Yerkes stepping down the same year that Kinsey’s research emerges can give the illusion that there was a changing of the guards within the field of psychology. However, that is not necessarily the case- Yerkes and Kinsey were, at the very least, professionally close. They maintained letter correspondences to each other for years, and even spent time getting to know one another personally.

When Yerkes and other members of the committee scheduled a visit in the fall of 1942 to the Institute at Indiana University, Kinsey invited Yerkes to his home to meet his family.[12] On Christmas Eve, Kinsey wrote to Yerkes, “Of course it encourages us tremendously to have your approval on what we have done… It was delightful to have become better acquainted with you personally. Mrs. Kinsey, the Martins, and the others join in this.”[13]

Kinsey even gave a special acknowledgement to Yerkes in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. He stated, “Special mention should be made of the cordial support given by Dr. Robert M. Yerkes, who has served as Chairman of the Research Council’s committee since its inception more than twenty-five years ago.”[14] Indeed, Yerkes assisted in more ways than one. Not only was he instrumental in approving the funding for research, Yerkes wrote letters to the Army Commission recommending draft deferment for three of Kinsey’s research assistants, Dr. Clyde E. Martin, Dr. Vincent Nowlis, and a Dr. Ramsey. As Yerkes told the Army Commission, “…the program of research concerning problems of human sexual behavior and social adjustments, for which Professor Kinsey is responsible and in which Dr. Nowlis is to assist him, is largely supported by the above Committee. In our opinion, the research is of very great practical importance for our public health and welfare.”[15]

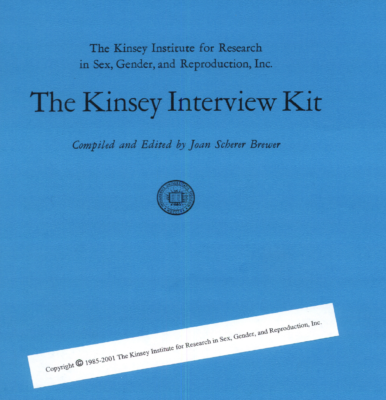

In examining The Kinsey Interview Kit, one sees the way in which the questionnaire categorized individuals onto a chart, removing any semblance of humanity or individuality from the process. From the researcher’s perspective, a person is a data-point among many. Kinsey’s study incorporated an interview process to gather his data, recruiting research assistants to conduct the work. Researchers started with more mundane questions, such as their age and marital status, then increased in sensitivity as the conversation progressed. Researchers covered a variety of topics which included social and economic data, psychological tests, as well as physiological, heterosexual, and homosexual data. As interviewees described their lives, interviewers filled out a chart with designated codes and symbols to categorize individuals and their behavior with classifications such as BD for “bull-dyke,” Z for “zoophilia”, and three check marks for “alcohol, excessive, or abuse.” Interviewers were instructed to speak clearly and frankly, advised that speaking in euphemisms denoted shame for the interviewee. For example, if someone stated, “we slept together,” interviewers were told to ask the follow-up question, “did you have intercourse?”

As the Interview Kit outlines, “to make the admission of behavior easier we placed the burden of denial on the respondent.” Instead of asking the person if they ever masturbated, they framed the question with an added assumption; how old were they when masturbation began. Reassuring and supportive language was periodically employed- not to encourage exaggeration or to reward “admissions of bizarre or extreme behavior,” but rather to add non-evaluative statements like, “It’s good you remember so accurately.” This was not done as a source of validation for the interviewee, the researcher was not holding space for their subject and providing support. It was instead to maintain “an elastic control of the interview.”

Researchers incorporated a conclusion phase after interviewees complained the process left them feeling exploited. They provided what they called a “cooling off” period, thanking them for their time and offering an opportunity for the interviewee to ask their own questions. Some people ended the experience remarkably upset as a result of recalling traumatic events. Thus, the researcher felt obligated to spend a little more time with the individual before moving on to the next person, according to the document.[16]

While the Kinsey Scale proved that sexuality is much more complex than previously known, the premise was still rooted in the assumption there was something fundamentally wrong or abnormal about one’s sexuality, and that the field of science would produce the answers to the “gay problem.” As Kinsey explained to Yerkes, “There are different racial stocks to compare. These comparisons are not only interesting, but very often provide an understanding of the phenomenon which can not be obtained from observation of it in a single group.”[17] This is striking as it echoes the racialized understanding of sexuality from early eugenicists and sexologists. At face value, it’s only logical that Kinsey would want a large, diverse research pool, and Kinsey’s research did challenge prevailing psychological theories, but factoring in Yerkes’ instrumental role in the eugenics movement, Kinsey’s statement is arresting.

Alfred Kinsey’s research is credited as revolutionizing our modern understanding of sexuality, but that is debatably a misnomer. The proximity to eugenicists should make us suspicious of attributing Kinsey with such a title relating to the field of LGBTQ+ mental health. Funding, approval of research methods, and intellectual support of Kinsey’s research was backed by the very institutions and individuals who propagated a pseudo-science of disdain. In fact, Paul Gebhard, Kinsey’s successor at the Institute for Sex Research, presented his study entitled, “Sexuality in the Post-Kinsey Era,” at The Eugenics Society in London in 1978.[18] This suggests that eugenics never escaped public consciousness, it only reproduced itself in advanced forms, with new research.

Applying Foucault’s theory of biopolitics and biopower to Kinsey’s research illuminates how the methodology fits neatly within the dialectic of the dominant class. Foucault states that biopower is essential in a capitalist system; people’s bodies are only viewed as a means of production and economic growth. If the body is not serving financial gains, then it no longer serves a function in society. By deconstructing the taboos and misconceptions surrounding sexuality, gay people could better assimilate into a capitalist society and consequently wouldn’t be a burden on the system and its institutions. Foucault describes the twentieth century as a rupture on the mechanisms of repression. Sexual taboos were now seen with relative tolerance; associating homosexuality with perversion diminished, and their condemnation by the law waned.

Foucault clarifies, however, “If the politics of sex makes little use of the law of the taboo but brings into play an entire technical machinery, if what is involved is the production of sexuality rather than the repression of sex, then our emphasis has to be placed elsewhere.”[19] According to Foucault, the cycle of sexual repression coincides with economic fluctuations. In this way, Kinsey’s research can be understood as a “deployment of sexuality organized by power in its grip on bodies and their materiality, their forces, energies, sensations and pleasures.” Foucault advises society to break away from the “agency of sex” and encourages us to counterattack with an emphasis on bodies and pleasures.[20]

Mona Lilija and Stellan Vinthagen’s essay, “Sovereign Power, Disciplinary Power and Biopower: Resisting what Power with what Resistance,” provides insight on how Foucault’s theory of biopower can be understood as a methodology for resistance. According to Lilija and Vinthagen, resistance is defined as a reaction to power, the traits of a “power strategy/relation” impact the types of resistance movements that will ultimately prevail. If resistance is shaped by power, then it is essential to investigate the features of a resistance “that are linked to or emanate from what kinds of power.”[21] As stated by historian Henry L. Minton, homosexuals and transgender people were not passive prey to the scientific and medical field, but rather “active agents in utilizing scientific research as a vehicle for homosexual rights.”[22] Using methods of scientific knowledge production and enterprise to their advantage, they carved space within the community to validate their existence and challenge the status quo of tyranny.

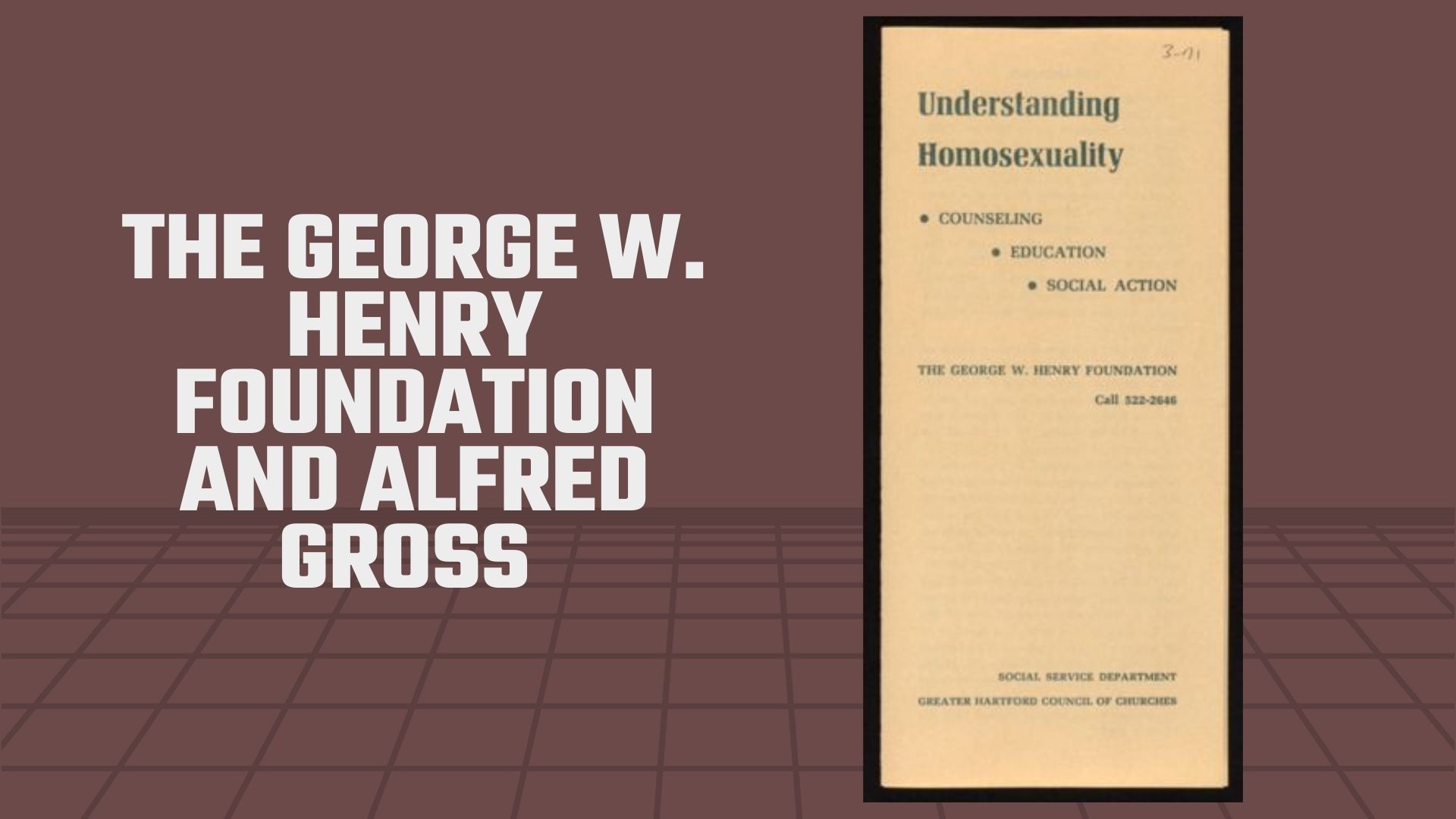

A prime example of homosexuals taking an active role in research, education, and community engagement was Alfred Gross and his collaboration with psychiatrist George W. Henry. They began working together in the 1930s until Henry’s death in 1964, studying and treating sex offenders. In 1948, inspired by Kinsey’s research, they established the George W. Henry Foundation in New York City; Gross became Henry’s right-hand man. Alfred Gross was a closeted gay man who was removed from his position as an Episcopal priest in 1937. Gross sought Henry out for psychiatric services; Henry was known as a specialist in homosexuality due to his involvement with a sex variants study.[23] Henry was not necessarily an ally in the traditional sense- a year after his passing it was stated in documents that “George W. Henry hated homosexuals and homosexuality with a passion but he thought they were getting a raw deal and needed help and so the Foundation was started.”[24]

Nevertheless, a group of Quakers approached Gross and Henry to establish a social agency devoted to helping young men who were arrested on charges pertaining to homosexuality. While Henry was appointed psychiatrist-in-chief, according to Harry Minton, it was Gross who really ran the day-to-day operations. As the organization grew, Henry provided the impression of authority and shield of respectability which was invaluable for assisting a marginalized population. Over time, Gross’ role expanded to include ghostwriting Henry’s official reports. “Using Henry as a front enabled Gross to carve out a career for himself as a social worker devoted to helping homosexual men in trouble with the law. Moreover, Gross was utilizing Henry’s attributed authorship to voice his own views and concerns.”[25]

Initially, the Foundation’s goal was to guide men to lead a more discreet lifestyle, as most of the men were of low-income and caught committing sex acts in public. Gross provided the client with probationary casework, and along with the help from clergy and physicians, they received religious and medical counseling, as well as psychotherapy. In the first few years of the Foundation’s inception, there was an emphasis to “adjust the homosexual to fit into society.”[26]

Indeed, the Henry Foundation emulated the rhetoric echoed by other early twentieth century sex researchers. In the 1950 Second Annual Report, Henry asserted that while homosexual people are not insane or mentally defective, “they do represent a serious social problem.” He called attention to flamboyant, exhibitionistic homosexuals as a source of public indignation and claimed more conservative men don’t have the power to “conduct housecleaning and police the more flagrant members of the group…as we have so often said, it is they who in the long run will have to suffer for the sins of the fairies.”[27] In the early days of the Foundation, there was a greater emphasis on restoring homosexual people back to their social usefulness. However, as the years progressed, Gross took on a more central role and became more vocal about the public resistance against discrimination of homosexuals.

While his goals and views somewhat aligned with the burgeoning homophile movement, Henry and Gross avoided any association with such groups.[28] In the early 1950s, homophile groups like the Mattachine Society, ONE, inc., and Daughters of Bilitis were some of the first activist organizations in the country to advocate for gay and lesbian human rights.[29] Homophile was a collective term that signified someone was a friend and advocate for homosexuals. According to Gross, the public perception of these homophile groups would have been the “kiss of death,” for their organization if they partnered early on.

According to Harry Minton, “In part, this reflected their homophobic attitudes and distrust of homosexuals acting as a collective force.” In fact, Alfred Kinsey was possibly more sympathetic to homophile organizations and yet, he too avoided any official association with the groups and any known homosexuals, out of fear that his credibility would be compromised.[30] However, all of this shifted once George Henry died in 1964, and the organization was reconfigured. Gross became the executive director and board members were replaced with people who had direct homophile connections. Then in 1965, an Episcopal priest in Hartford, Connecticut named Canon Clinton Jones became interested in the work conducted by the George W. Henry Foundation. Once the Hartford chapter was established, the Foundation became permanently amiable with homophile organizations.[31]

Canon Clinton Jones was a remarkable individual who, like Gross, took an active role in the fight for gay and transgender rights as he spearheaded one of the first major LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations and mental health supports in the state. He transformed community care and support, inspiring generations to come. A Connecticut native and secretly a gay man himself, Jones took a special interest in homosexual research when he was appointed to the Rehabilitation Committee for the Greater Hartford Council of Churches.[32] The Committee examined a variety of issues including treating drug addiction and transitioned people from in-patient mental health institutions back into public life. The Rehabilitation Committee began studying issues related to homosexuality, but Jones decided another separate committee needed to be established. This inspired the formation of the group Project H.

In partnership with Trinity College Psychology professor Dr. George Higgins and attorney Donald Cantor, Jones formed Project H in 1963. As the first homophile group in the state, Project H provided legal, educational, and counseling services for gay men in the Christian community. The group met at the Hartford YMCA with social workers, psychologists, and clergy for services. The origins of the name derived from the need for secrecy; the YMCA administrators were concerned about the signs displayed throughout the building that read “homosexuality,” and asked for a more discreet name; hence, Project H. In 1966, Jones received complaints that the Connecticut Department of Corrections had established a “Cell Block G” to house all gay and transgender incarcerated people.

Canon Jones negotiated meetings in the prison to speak with the warden, wherein the warden claimed the separation was actually for the protection of the Block G inmates. Canon Jones discovered, however, that they were living in worse conditions than those in the general prison population. They had limited access to the outdoor yard and were forced to eat dinner at 3:30 in the afternoon to avoid interaction with other inmates. Canon Jones was not able to convince the prison to dismantle Cell Block G, but he was able to provide pro bono counseling to prisoners on a weekly basis, and was a practice he continued until his retirement in 1986.[33]

Canon Jones and Dr. Higgins also founded the Twenty Club in 1971, a support group for transgender people. This extensive group met for over thirty years at Christ Church Cathedral in Hartford, providing counseling and psychiatric services, which later evolved into gender-affirming surgery. The following year, Canon Jones and Higgins founded the Gender Identity Clinic of New England, a network of social workers and counselors who provided transgender people with mental health treatment, hormone therapy, and surgery.

According to Higgins, “we started out enthusiastically and stupidly,” and the doctors at Mount Sinai Hospital in Hartford eagerly provided them a space. Founded in 1923, Mount Sinai was established to provide a hospital for doctors of Jewish descent to work. Other hospitals discriminated against their religion and denied the doctors positions. After they created a new obgyn group, the team of doctors and administration were very interested in “making a splash,” as Higgins put it, and wanted to assist in chartering the first transgender medical care in the state.[34]

Consisting of a lawyer, a priest (Canon Jones), a social worker, two psychiatrists, a psychologist (Higgins), and an endocrinologist from the Veteran’s Hospital, this multidisciplinary group’s objective was to provide individualized care. Each month the Gender Identity Clinic team met to discuss patient care, policies, laws, and solutions to issues. In November 1973, they convened to discuss the costs associated with gender-affirming care, as well as legal problems associated with transgender people using public restrooms. They concluded that a transgender woman would have greater difficulty entering a men’s room, “perhaps many more difficulties than such a person using the woman’s [sic] restroom which are usually equipped with individual stalls.”

Additionally, they discussed the legal parameters of providing surgeries. They determined they would not perform a surgical procedure if the person was married and their spouse did not agree with the treatment plan. They also decided they would not provide medical treatment to minors. They did, however, avail themselves for consultatory services and psychological help in the case of minors with gender dysphoria.[35]

The cost of receiving care was vast and complicated, depending on the needs of the individual. Patients were required to pass multiple psychological tests and consultations which were between $45 and $50 each session. Hysterectomies were between $450 and $500, facial reconstruction surgery was approximately $1500, the team evaluation cost was $530, and vaginal surgery was $16,000. Some of these costs were required to be paid in-full by the patient prior to the procedure. If the financial barrier wasn’t enough, there was a long and arduous process of evaluations to qualify for care. If the person had a low-IQ, history of mental illness, severe obesity, or depression, there was a chance they were denied care.

If the physical, psychiatric and social evaluations determined the person was disabled due to gender dysphoria and unable to work because of their physical or mental impairment for at least one to two years, then they may qualify for financial assistance with their treatment. During this time, gender dysphoria was still categorized as a personality disorder that is “highly rehabilitative but incapacitating.”[36] Today, gender dysphoria remains in the DSM-5, taking the place of gender identity disorder in its classifications. According to the American Psychiatric Association, the categorization is intended to facilitate clinical care and access to insurance coverage. However, as useful diagnostic terms can be within the framework of capitalistic medicine, the nature of categorization carries a stigmatizing weight.[37]

Unquestionably, the path to receiving gender-affirming care was exhausting and full of obstacles. Once an individual was accepted into the gender identity program, they were required to complete pre- and post- operation evaluations. After their intake interview and psychological evaluations, depending on their treatment plan, they may be subjected to more scrutinization. Most procedures required a minimum of two additional evaluations, but operations such as breast reduction demanded a third appraisal. Six months into the program they needed to undergo yet another evaluation and a fourth or fifth was added within thirty days of a scheduled surgery. The intake questionnaire inquired patients on their income, highest education, race, ethnicity, and almost seventy questions related to the person’s religious background and their personal relationship to their faith. It also asked about their political beliefs, their desire for other physical anatomy, and how they related to gender binary norms.[38]

According to Higgins, they were not looking for symptoms and markers, but rather listened to the individual’s story, given their realities and circumstances. There wasn’t a one-size-fits-all approach; everyone was handled on a case-by-case basis. Higgins stressed the importance of individualistic care, asserting that modern psychiatry is far too quick to throw pills at a situation rather than listening to the person’s needs. He claimed that the psychological and IQ evaluations were only instilled as safeguards to screen out serious pathology or developmental disabilities. Ultimately, they wanted to ensure the person had the mental capacity to consent. If they had behavioral health issues, it didn’t necessarily mean they couldn’t go through with the transition process, but it did give doctors pause before proceeding; patients may not necessarily get the full breadth of care they were seeking.

However, Higgins also illuminated the policies that effectively supported the individual’s transition and ensured it would not negatively impact their livelihood. Canon Jones went to the patient’s place of employment and spoke with their employer about the “experimental work” they were conducting. Canon Jones arranged a meeting to sit down with staff or human resources and explained the person’s pronouns and bathroom accommodations to assure the transition was well-received. Trying to avoid backlash and wrongful termination, they were more worried about the patient being accepted than anything else. They didn’t want the patient’s quality-of-life to suffer from receiving treatment. Higgins remembers employers, by and large, receiving this information positively and were very accommodating. When the first state employee underwent transition at the Clinic, Canon Jones met with an official from the state’s Human Resources. They expressed to Canon Jones that it was of great importance to the state to “set the tone and do this right.”[39]

Even by today’s standards, The New England Gender Identity Clinic was one of the most progressive organizations. However, they were not without their own biases and prejudices. In April 1978, a patient named Rafael Ayala was dismissed from the Clinic’s program. According to the dismissal letter, Ms. Ayala forged a prescription requesting two thousand Premarin and one thousand Provera tablets. In addition to her therapy and treatment termination, the State Department of Welfare was also informed. The letter informed Ayala, “you will have to go elsewhere for your hormonal treatment and/or any other treatment regarding your gender problem.”[40] There was nowhere for her to go as an alternative. According to Higgins, there was a group of Puerto Rican sex workers in Hartford who were not seeking care from the Clinic. He stated they were “Puerto Rican men who cross-dressed and would get into people’s cars and prostitute.” In Higgins’ account, Ayala was attempting to distribute estrogen to the sex workers and claimed they were not trans women, but rather men who presented as women to “boost sales.”[41]

Without speaking to Ayala herself, there would be no way of confirming Higgins’ account of the events. However, given the high cost of gender-affirming care and the exhausting amount of psychological evaluations, it is more likely they were trans women who did not want to jump through hoops and barriers to receive prescription treatment. This incident reveals that even in spaces that are challenging the status quo of therapeutic and medical care, these spaces are not immune to harmful, ableist, racist, sexist, or classist treatment of marginalized peoples. This matter regarding Ms. Ayala may also provide an explanation as to why the majority of patients receiving care at the clinic were white. There were certainly transgender people of color, but white patients outnumbered Black and Latino cases. Exorbitant costs and assessments by white doctors who carried their own discriminations may explain why there is limited evidence regarding gender-affirming care for people of color during this time period.

Despite this reality, Canon Jones’ efforts were some of the first of its kind to advocate for psychological, legal and spiritual support for homosexual and transgender folk. Canon Jones was initially inspired by the work of George W. Henry Foundation, but over time his efforts actually transformed the role of the organization and galvanized the gay and transgender communities in Connecticut to coalesce to form additional cooperatives, some of which are still active to this day.

In fact, according to Connecticut “ourstorian” Richard Nelson, the only substantial counseling services to emerge from the George W. Foundation was orchestrated by Canon Jones exclusively.[42] While Jones is certainly a vital figure in our understanding of anti-eugenics and the creation of new pathways for queer wellness, none of this work was possible without a man named Foster Gunnison Jr. and the homophile movement. Gunnison maintained a steady correspondence with both Alfred Gross and Canon Jones, and urged them to incorporate the philosophy of the homophiles to ensure individuals and communities were provided with quality, compassionate care.

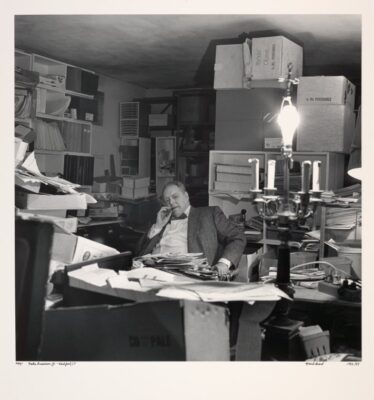

Foster Gunnison Jr. was an avid LGBTQ+ rights activist in Hartford and collected a substantial archive which is now housed at the University of Connecticut archives. After earning his Masters in psychology and philosophy at Trinity College, Gunnison remained in Hartford and founded his own organization entitled The Institute for Social Ethics which he described as a “libertarian-oriented research facility and think tank for controversial social issues.” Operating out of an apartment next to his home residence at Bushnell Towers, Gunnison published the pamphlet “An Introduction to the Homophile Movement” in 1967. He provided the reader with extensive critique of the field of psychiatry as well as the philosophy of the homophile.

Gunnison recognized that despite Kinsey’s research, the dominant perceptions of gay and transgender people were that they were mentally ill or “emotionally handicapped.” He inquired that if that was the case, he didn’t know of any other group that was collectively classified as sick; “have ever sought to rise in a body and demand their right to be sick, or demand that their sickness be accepted by society as a valid mode of human self-expression?” Gunnison invalidated the use of rehabilitation for homosexuality, he stated there is no cure and because psychiatry stigmatizes non-normative sexuality and as a result, LGBTQ+ people do not go to therapy, even if they might benefit from it.

They were taught that psychiatry is the enemy of homosexuals and that the theories are reminiscent of Victorian pseudo-science, taking the place of the church as the dominant authority of morality. Mental illness became a euphemism for sin and deviancy; normalcy was law. “In this view, psychiatrists and their theories are held to be mere servants to a prevailing morality and ethical status quo, and a threat to individuality, diversity, and growth.” Gunnison identified a chasm between the organized homophile movement and the field of psychiatry; those who would benefit the most from receiving mental health treatment were deterred from seeking care.[43]

He called for a multifaceted solution which included the visibility of LGBTQ+ individuals in public life, film and media, and advertisements. Gunnison advocated for “T.V. programming featuring open and constructive treatment of homosexual themes.” He also advocated for creating spaces: “the continual opening of new bars, restaurants, lounges, shops, and private or open clubs catering to homosexuals.” Lastly, he encouraged what he called outer-directed work which sought to combat myths and distortions associated with queer identity. Protests and public demonstrations fit under this outer-directed work umbrella, as well as ongoing dialogues with institutions.[44] Truly, outer-directed work became essential for LGBTQ+ people to define intellectual and physical space for themselves in Connecticut. The contributions of Gunnison and Jones were precursors to a wave of activism and a metamorphosis of public space throughout the state.

Along with Foster Gunnison’s efforts, the larger homophile movement in Hartford was aligned with the theory of space as argued by Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre. Don Mitchell’s inquiry of Lefebvre offers insight and analysis in the fight for public space. Mitchell illustrates how social action such as protests, lawsuits, and the active taking of space in a city, can serve as a lodestar for a more equitable society. As stated by Mitchell, Lefebvre described the homogeneity of rural life and its contrast with cities; the city is the site of “where difference lives.”

Urban sites are also where difference resides in a state of active tension- a struggle with one another to obtain access to space. According to Lefebvre, “the right to the city manifests itself as a superior form of rights: right to freedom, to individualization in socialization, to habitat and to inhabit. The right to the oeuvre, to participation, and appropriation, are implied in the right to the city.”[45] The oeuvre is the city; the site where all citizens are engaged, where people converge with one another to combine “the past, the present, and the possible.”[46] While proponents of eugenics were concerned with the regulation of access to space, queer liberation demanded admittance by participating in the public sphere, unapologetically. As a result, Hartford became the site for monumental changes towards LGBTQ+ rights. A large movement grew throughout the 1960s and 70s, as organizations emerged out of the need to secure safe, therapeutic space for LGBTQ+ communities.

In 1968, the Kalos Society (derives from the Greek word, καλώς (kalós) meaning “good or noble man”) started as a support group for the counselees of Project H, but later evolved into an advocacy, psychological support, and social organization. While the Kalos Society preceded the Stonewall Riots, the events in New York City inspired the organization to mobilize and become more radical. Keith Brown, Harry Williams, and Ken Laughlin were the three original founders and according to them, the goal of the organization was to “learn to like ourselves and then we could become political.”

The organization served several purposes: a social organization and meeting place for people outside of the bar scene and a group therapy space for gay men. Later, the inclusion of members Ken Bland and Ron Melvin helped politically galvanize the group. The goal of their political activism was to obtain equal rights and fair treatment by educating the public. According to Keith Brown, both Bland and Melvin “worked very hard to make sure our voices were also being heard in the Hartford political arena.” Unfortunately, both men died of AIDS and did not get to witness the results of their tireless efforts.[47]

The Kalos Society was involved in organizing several social events and political protests throughout the state in the early 1970s. They also began publishing a newsletter called The Griffin, promoting events and legislative news. In 1971, Kalos Society attempted to host a picnic at Goodwin Park in the South end of Hartford. Locals protested the picnic with 400 residents signing a petition to prohibit the group from gathering at the park. The petition stated that “we feel that this group prohibits the natural law set down by God. We therefore request that the City of Hartford be enjoined from issuing a permit for the park for this group.”

In the wake of this controversy, local authorities issued an ordinance that required a special permit for public speeches in Hartford parks.[48] Despite the opposition, the Kalos Society helped organize the Connecticut Liberation Festival, the state’s first Pride festival, in 1971. While the members felt it did not live up to their expectations- citing disorganization and a low turnout- the gay community remembered it as the first major effort in a communal festival, celebrating and taking up space in public, in an outdoor setting.[49]

Later that year, the American School for the Deaf in West Hartford suspended teacher Ken Bland without pay for appearing on local television representing the Kalos Society. The school administration defended their actions by stating they were simply responding to concerns from parents. They offered Bland an alternative position as a custodian, but he turned down the demotion. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) got involved and the events inspired the Kalos Society to advocate for the first gay rights legislation in the state.[50] The Gay Rights bill did not make it to a vote and did not pass until 1991. However, the efforts of the Kalos Society were foundational seeds of LGBTQ+ justice in the state of Connecticut.

In early 1973, members of the Kalos Society reached out to the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) in Boston and inquired about establishing a congregation in Hartford. The denomination was part of a larger network of churches for gay Christians that was established in California in 1968.[51] Originally located on Amity Street, MCC’s primary mission was to communicate to LGBTQ+ people that God loves them. All of the Kalos Society’s funding and resources, a total of $800 dollars, went to start MCC, and thereby disbanded the group. By 1974, the congregation grew and moved to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The space was used for worship services, dinners, events, and rap sessions. MCC was then accepted into the Greater Hartford Council of Churches and operated the Gay Switchboard, which functioned as a source of information and referral.

Reverend Jay Deacon was the first pastor of the Hartford church, and was a constant advocate for social justice. He and other congregation members organized protests and sit-ins to speak out against economic injustice and for fair housing practices. However, MCC did face backlash for their visibility and outspokenness. In 1978, Reverend Deacon’s car was set on fire in Hartford. After the incident he spoke out, “We do not need these institutions and churches that cannot and will not affirm our rights and our humanity. We must build communities and institutions of our own.” Reverend Deacon remained at MCC for another year until he became the pastor of Good Shepherd MCC in Chicago. On July 14, 1978, Mayor George Athanson proclaimed it Jay Deacon Day in honor of his contributions to the city of Hartford.[52]

The church also published a newsletter entitled MCC News, but in 1982, a man named John Crowley wanted the publication to reach a wider readership. It was then that MCC News became Metroline, Connecticut’s gay community magazine. Metroline was a free, biweekly publication and could be found in bars and gay-friendly spaces throughout Connecticut and western Massachusetts.[53]

For decades, however, Metroline was a cornerstone for gay cultural life in the region. It advertised local businesses and events, informed on relevant political legislation, and offered advice columns. Additionally, they provided a comprehensive health directory for residents to find queer-friendly doctors and therapeutic services. Despite Metroline ending in early 2010, a victim of the technological revolution, Metropolitan Community Church’s Hartford congregation continues to gather for worship to this day and is now located in the same building as The Church of the Good Shepherd.[54]

Kalos founding member, Keith Brown, decided to take his activism to the airwaves on Thanksgiving night of 1980, and he’s been broadcasting ever since. Gay Spirit Radio on WWUH 91.3 was another branch of this movement and is the oldest, longest-running LGBTQ+ radio program in the country. Due to its longevity, Brown’s meticulous attention to detail, and the help from consultant Ira Revels, Gay Spirit Radio functions as an oral history archive in its own right. Covering local and national gay and transgender news, reporting important events and political legislation, and interviewing local activists, Brown has never been a “crowd pleaser.” He often used his radio program as a voice of dissent, even to groups like Connecticut Pride organizing committees.[55]

Brown was always a fearless provocateur- in high school he cut out and pinned a red “H” to his shirt to signify “homosexual.”[56] In the time of his youth this was a daring act, as Brown described himself as “old enough to remember when gay men danced together and only behind closed doors (or darkened windows).”[57] Broadcasting queer-specific news was also considered a revolutionary act at the time, but that never stopped him. Over the years, Keith Brown interviewed a multitude of activists and artists including Alan Ginsberg, Anthony Rapp, Anne Stanback, and local trans- advocate Diana Lombardi.[58]

Brown’s Gay Spirit Radio reveals how LGBTQ+ people can occupy public space in a unique way. Spending most of his life fighting for LGBTQ+ rights on the streets, he transported gay life into sonic space; transmitting and transmuting the airways with talks of justice. Brown began his career working alongside Canon Jones to create therapeutic space and over time, he realized that the struggle was deeply political. More broadly, Hartford’s LGBTQ+ activism illuminates the intersection between politics and mental health, the dire urgency to heal and laying claim to do so.

Another crucial example of grassroots LGBTQ+ therapeutic space was the Heartroots Feminist Therapy Collective. Working out of the living rooms in their homes, former Hartford Hospital therapists decided to establish Heartroots to integrate the burgeoning feminist movement into the field of psychology. Their main focus was on the individual functioning within the political, social, and community framework, healing by building community and teaching cooperation. The task was to take a holistic view and ecofeminist approach that explored the sexual, social, and political environment of an individual. Moving beyond the sterile hospital setting and bringing therapy away from the asylum model and back into local communities, Heartroots provided a safe setting for women and queer people to support one another.

According to founder Loretta Wrobel, she gravitated to studying sociology and psychology, primarily to save herself. When she attended graduate school in New York City, she witnessed the height of the women’s rights movement. After she came back to Hartford and saw nothing was really going on in the way of women’s advocacy, and noticed a lot of rage and anger amongst her women clients, she and her coworkers at Hartford Hospital decided a separate women’s therapy organization was necessary.

Departing from traditional therapeutic methods, they sought to help women with their sexuality to navigate life and relationships. In a time before license qualifications and regulations, the therapists at the collective attended training workshops and then practiced on themselves before applying a methodology to their clients. Additionally, there was a socialization component to Heartroots; camping weekends, a feminist library, and coffee hours were incorporated. There was an emphasis on becoming an integrated person, providing support and community. In addition, organizations like the YWCA and the Trinity College Women’s Center were very supportive in hosting events on behalf of the Feminist Therapy Collective.

Wrobel recognized that a comprehensive understanding of race and class were essential to providing adequate services. Coming from a working-class background herself, she interacted with a wide range of people in her community. When she worked at Hartford Hospital, it was obvious to her that there were inequitable treatment plans for people of color from Hartford versus a white person from Farmington. More than once, she received patient referrals from doctors and there was no prognosis listed besides the patient’s race; doctors did not want to provide care for women of color and simply passed them off to someone else.

Outraged by this, Wrobel worked closely with Black and Latina women through the Hartford Interval House. By providing services in the women’s shelter, she learned that when women reported incidents of domestic violence, they were subjected to cruel treatment by police, which put them in more danger. As a result, she maintained the position that everyone deserves access to care and implemented a sliding scale for payment.[59]

Despite the dominant narrative of eugenics that pervaded modern society, queer identities converged spatially, both in physical and intellectual space. The transformation of the field of mental health and cultural life cannot and should not be attributed solely to men like Alfred Kinsey. Instead, the efforts of early activists, researchers, philosophers, and clergy uncover the true dimensions of radical change. Outside and inside churches, prisons, hospitals, out into the street; through media publications and airwaves, reaching all the way to their homes being used as therapeutic space. The act of claiming space for themselves is what transformed the dominant narrative towards LGBTQ+ people in the twentieth century. Intellectual space was claimed through the philosophy of the homophile movement as documented by Gunnison.

Organizations like Heartroots and the Gender Identity Clinic offered individualized, gender identity-centered mental health care, and demanding access to public space through visibility, and protest, were part of the process that de-pathologized and decriminalized their bodies. The scientific community did not liberate queer identity from the margins, average citizens did it for themselves. It was not perfect; there were still many barriers and prejudices that negatively affected queer people of color. That said, Hartford was the site of some of the earliest gay and transgender freedom movements. Through the courageous efforts of LGBTQ+ residents in the twentieth century, who carved out their own spaces and communities in Connecticut, they did not wait for institutional legitimacy for their liberties. Not only did they demand for their right to exist, they claimed their right to public space, and their right to their bodies.

Footnotes:

[1] Minna Stern, Alexandra, “Sexuality,” Pathways: Eugenics Archive, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, April 29, 2014, accessed November 22, 2022. http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/tree/535eee2d7095aa0000000258.

[2] Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Connecticut Child Study and Treatment Home, September 25, 1956, Joint Board of Mental Health, 1948-1951, Connecticut State Library.

[3] Stein, Melissa N., Measuring Manhood: Race and the Science of Masculinity, 1830-1934, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), pg.169.

[4] Stein, Melissa N., Measuring Manhood, pg.169-177.

[5] Stein, Melissa, Measuring Manhood, pg.178-201.

[6] Gur-Arie, Rachel, “American Eugenics Society (1926-1972),” Embryo Project Encyclopedia, November 22, 2014, accessed February 5, 2023, http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8241.

[7] American Eugenics Society, Organized Eugenics, (New Haven: American Eugenics Society, 1931).

[8] Minna Stern, Alexandra, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in America, (Oakland: University of California, 2016), pg. 11.

[9] “Articles of Organization of The National Research Council,” The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, May 19, 2016, accessed April 15, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20160519172226/http://www.nationalacademies.org/nrc/na_070358.html.

[10] Kendall, Emily, “Kinsey Scale,” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 6, 2022, accessed May 6, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/sexual-orientation/additional-info#history.

[11] NRC: Committee for Research on Problems of Sex Agenda for Meeting of April 29, 1948, Folder 1458, Robert Yerkes Papers,(Series 2, Box 80), Yale University Archives and Manuscripts.

[12] Kinsey, Alfred, Alfred Kinsey to Robert Yerkes, June 4, 1942, Bloomington, Indiana, Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey Era Correspondence, Kinsey Institute Library & Archives.

[13] Kinsey, Alfred, Alfred Kinsey to Robert Yerkes, December 24, 1942, Bloomington, Indiana, Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey Era Correspondence, Kinsey Institute Library & Archives.

[14] Kinsey, Alfred, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1948), vii.

[15] Yerkes, Robert, Robert Yerkes to the Army Draft Commission, February 23, 1944, New Haven, Connecticut, Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey Era Correspondence, Kinsey Institute Library & Archives.

[16] The Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, The Kinsey Interview Kit, compiled by Joan Scherer Brewer, (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1985).

[17] Kinsey, Alfred, Alfred Kinsey to Robert Yerkes, January 14, 1941, Bloomington, Indiana, Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey Era Correspondence, Kinsey Institute Library & Archives.

[18] Gebhard, Paul H., Sexuality in the Post-Kinsey Era, Dr Paul H. Gebhard Era Correspondence Collections at the Kinsey Institute Library & Archives, (Bloomington, Indiana, 1978).

[19] Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction, (New York: Vintage

Press, 1990,) pg. 114-115.

[20] Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality, 152-157.

[21] Lilija, Mona and Stellan Vinthagen, “Sovereign Power, Disciplinary Power and Biopower: Resisting what Power with what Resistance,” Journal of Political Power, Vol. 7, No. 1, (2014).

[22] Minton, Henry L, Departing from Deviance: A History of Homosexual Rights and Emancipatory Science in America, (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2001) pg. 88-93.

[23] Minton, Henry L., Departing from Deviance, pg. 94-95.

[24] Project H Committee Notes, October 21, 1965, George Henry Foundation, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 1, Folder 3, GLBTQ Archives, Central Connecticut State University.

[25] Minton, Henry L., Departing from Deviance, pg. 102-103.

[26] Ibid, pg. 103.

[27] Henry, George W., “George W. Henry Foundation Second Annual Reports,” Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 3, Folder 12, GLBTQ Archives, Central Connecticut State University.

[28] Minton, Harry L., Departing from Deviance, pg.109.

[29] “Before Stonewall: The Homophile Movement, LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide,” Resource Guides, Library of Congress, accessed April 25, 2023, https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/before-stonewall.

[30] Minton, Harry L., Departing from Deviance, pg. 109.

[31] Ibid, pg. 110.

[32] Gifford, Emily. “An Early Advocate for Connecticut’s Gay Community.” Connecticut Explored, Summer 2014, https://www.ctexplored.org/an-early-advocate-for-connecticuts-gay-community/.

[33] George Henry Foundation, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 1, GLBTQ Archives, Special Collections, Central Connecticut State University.

[34] Higgins, George, Personal Interview, Interview by Eve Galanis, March 31, 2023.

[35] Gender Identity Clinic Meeting Minutes, November 13, 1973, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 9, Folder 5, GLBTQ Archives, Special Collections, Central Connecticut State University.

[36] Ibid, Folder 5.

[37] American Psychiatric Association, “Gender Dysphoria,” 2013, accessed April 29, 2023, https://www.psychiatry.org/file%20library/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/apa_dsm-5-gender-dysphoria.pdf.

[38] Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 9, Folder 27, GLBTQ Archives, Special Collections, Central Connecticut State University.

[39] Higgins, George, Personal Interview, Interview by Eve Galanis, March 31, 2023.

[40] New England Gender Identity Clinic to Rafael Ayala, April 17, 1978, Hartford, Connecticut, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 9, Folder 5, GLBTQ Archives, Central Connecticut State University.

[41] Higgins, George, Personal Interview, Interview by Eve Galanis, March 31, 2023.

[42] Nelson, Richard, Personal Interview, Interview by Eve Galanis, February 27, 2023.

[43] Gunnison, Foster Jr., “An Introduction to the Homophile Movement,” George Henry Foundation, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 3, GLBTQ Archives, Central Connecticut State University.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Mitchell, Don, The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space, (New York: The Guilford Press, 2003), pg.10-18.

[46] Lefebvre H. 1967, “The Right to the City” and “Theses on the City, the Urban and Planning”, in Kofman E. and Lebas E., Writing On Cities-Henri Lefebvre, (Oxford: Blackwell; 1996), pp. 147–159, 177–181.

[47] Brown, Keith, Personal Interview, Interview by Eve Galanis, March 24, 2022.

[48] Kalos Society Folder, George Henry Foundation, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 6, GLBTQ Archives, Central Connecticut State University.

[49] The Kalos Society-Gay Liberation Front, The Griffin: News of Gay Liberation, November 1971, Roz Payne Sixties Archive, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, https://rozsixties.unl.edu/items/show/587.

[50] Kalos Society Folder, Central Connecticut State University.

[51] Mann, William, “A Brief History of Connecticut Gay Media,” Connecticut Explored, Winter 2020-2021, accessed April 3, 2023, https://www.ctexplored.org/a-brief-history-of-connecticut-gay-media/.

[52] Nelson, Richard, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer + Tour 2 Stop 8,” Furbirdsqueerly, March 2, 2023, https://furbirdsqueerly.wordpress.com/2023/03/02/lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender-queer-tour-2-stop-8/.

[53] Mann, William, “A Brief History of Connecticut Gay Media.”

[54] Metroline, 1982-2010, GLBTQ Archives, Special Collections, Central Connecticut State University.

[55] Brown, Keith, Interview by Roxanne Gomes, Video, October 29, 2002. GLBTQ Archives, Special Collections, Central Connecticut State University.

[56] Nelson, Richard, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer + Tour 2 Stop 8.

[57] Johnson, Phillip D., “Recording the Moments of Our Lives,” Newsweekly, Vol 6., No. 32, 1997, Canon Clinton Jones Archives, Box 2, Folder 17, GLBTQ Archives, Special Collections, Central Connecticut State University.

[58] Revels, Ira and Keith Brown, Gay Spirit Radio Archive Project, 2022, accessed April 29, 2023, https://gayspiritradio.com/.

[59] Wrobel, Loretta, Personal Interview, Interview by Eve Galanis, February 27, 2023.