An examination of American history’s most pressing questions….

When historians are developing inquiry, we will often ask, “What questions in this era were people trying to answer? and “What questions do we as historians have when we try to understand this era?” In this article, I strive to answer these questions in examining the timeline from the creation of the United States through the Civil War. Additionally worth noting, this essay was also written bearing in mind that I’m a history teacher and developing inquiry is important both as a historian and as an instructor.

What questions were the people in this era trying to answer?

In order to understand what questions were being asked, it first depends on who you ask. Historical slant or perspective shapes inquiry. Time and location will also impact the questions being asked. Surely, the questions of white plantation owners in Georgia wouldn’t be the same as their slaves. Even the questions of Northern slaves wouldn’t have been the same as their Southern counterparts. The questions of the Iroquois are not the same as those of the Apache. It’s important when analyzing U.S. history, that we are diligent about who specifically we are talking about when we say, “the people,” because oftentimes what we find in American classrooms, is the absence of inquiry of marginalized peoples voices; what questions were they asking. Things didn’t just happen to them, they didn’t just float along while rich, white men asked the deep, pressing questions.

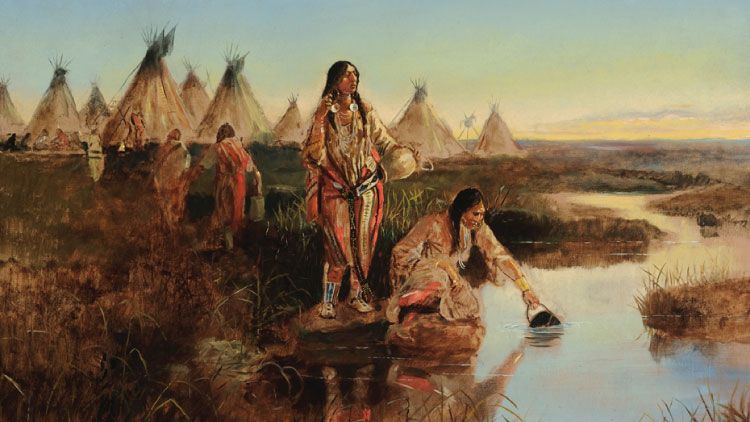

With that said, it seems like I couldn’t do Indigenous nations justice if I say what questions they were asking during these eras in one or two paragraphs. They’re not a homogeneous group, each one is more diverse than the next, with over two-hundred languages spoken among tribes. To suggest that they’re somehow this monolithic culture with common political and social commonalities, is to reinforce colonialism and cultural genocide. However, in the most general sense, it’s possible some questions that sprung up among nations may have included, What do we do with the white man? How should we retain our nations as we are pushed out of our homes? How do we deal with our people dying of disease? How do we resist enslavement and subjugation? How do we resist genocide?

Again, to be clear, depending on what colonizers the Indigenous nations were interacting with, would shape their questions. The question, what should we do with the white man, is a question that the Pawtuxet tribe may be asking in the Northeast, as Pilgrims were arriving on their coastline, ill-equipped to fend for themselves. It may have been asked by the Cheyenne and Sioux as whites pushed further and further west in the 19th century.

The question, how do we deal with our people dying of disease, is one that arguably continues in Native American society today. From the time of first contact, Indigenous people were not immune to European diseases, and millions died as a result. Today, Native Americans struggle with inadequate health care and have some of the highest rates of substance abuse and addiction.

The question, how do we resist enslavement and subjugation, would have been particularly relevant for tribes interacting with Spanish colonizers in the Southwest and California, forced to work under the encomienda system. Once it became clear that it was difficult to enslave Indigenous people, African chattel slavery became the solution.

Similarly, it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact questions enslaved people would have had during this era. They lived significantly different lives, depending on their geography and would have different needs and desires. With that said, some common questions could have been, How am I going to survive this? How do we retain our sense of personhood? How do we resist genocide? How do we carve out our freedom?

Carving out what freedom means, is inherently American. The Framers of the Constitution were asking the exact questions as their slaves. Their power, influences, methods and resistance tactics were drastically different, but the question seems to be the same. The movement of Transatlantic Enlightenment is the philosophy to which colonizers applied in North America to demand nationhood. According to Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, America was, “founded on ideals rather than hereditary claims made it both a participant in and a source of the dramatic shift in Western thought known as the Enlightenment.” Of course, ‘hereditary claims’ exemption only applied to landholding white men.

In any case, the Framers of the Constitution had an endless amount of questions when they were creating their version of a Democratic Republic. Some included, How should a people be organized? What does freedom mean? Who receives freedom and who does not? Is freedom contingent on another’s lack of freedom? What should the government protect its citizens from? How will the people be protected from their government?

Eric Foner’s historical analysis of American freedom reveals that the actualization of freedom has evolved over time, served a different purpose for individuals. Religious freedom is a cornerstone of colonization, even freedom from desire as observed in the Temperance movement. The question of freedom carried into the Antebellum period with Westward expansion. During this time, the people in power were asking, Which states would be free and which would be enslaved?

During the early decades of the 19th century, there was also an influx of immigrants coming into ports of entry, mostly from Europe. For example, in the 1840s, the Irish famine brought hundreds of thousands of refugees escaping starvation. Their questions may have been, How will I make a living? Will this country protect my rights as man? How will I adjust to this new life? Their questions would have surely changed as the nation entered the Civil War. Particularly, Irish Democrats living in New York, would have asked How do I set myself apart from Blacks? How do I show my allegiance to this country? What will happen when the slaves are emancipated? Will they take my job?

The Civil War also brought many questions, and they evolved as the war progressed. Lincoln and his allies could have been asking in the beginning, How do we keep this country together? How do we all get what we want? Do we have to end slavery? How much division needs to happen, to create union? Later they would have been asking, What will end this war? What will we do with newly freed people? Average people living in Connecticut would be thinking What can I do to help the cause? How can I preserve my personal economic interests? A small, but strong minority would be asking, How can we abolish slavery and bring equity and justice to all Americans?

What questions do we as historians have when we try to understand this era?

As a U.S. History teacher, one needs to mention slavery from the very beginning of instruction. As Ira Berlin said, “slavery existed from the earliest history of human society.” For students to comprehend Why would anyone ever be held in bondage, Berlin asserts, “in world history, slavery is the rule, freedom the exception.” The Civil War should not be the first time a teacher mentions slavery, that is an injustice and is arguably erasure. While not only being historically accurate, weaving inquiry regarding slavery throughout the 16th-19th century curriculum, allows students to understand the magnitude it grew to, how pivotal it was to global economies, and that the North benefited as much as the South. Other questions that are relevant to us include, Did the slaves emancipate themselves? How did slaves resist their condition? How does slavery reveal the best and worst of humanity? How did slavery change over time?

With regards to understanding the Revolutionary War and the consequential creation of the nation, I’m particularly interested in contradictions and paradoxes. For example, How do we reconcile with people like Thomas Jefferson, Framer of the Constitution and slaveholder? What’s the difference between having the power to do something versus the power over something? Reconciling with our “problematic faves” as we say in pop culture today, is the first step to understanding the nuance of the time when Thomas Jefferson was alive. By observing the man, his contributions as well as his disgrace, it allows students to dismantle this binary pattern of thinking. One must be mindful, however, that we’re not falling into presentism. While we are looking at this from a 21st century lens, we are not applying the same rules of human moral conduct as we would with those that are living today. Rather, we get an understanding of the culture as it was at the time, what did it turn into, and where is it today. Surely, any single current event news article will tell you we don’t have it all figured out. By analyzing the complexity of the life of Thomas Jefferson we see not only a contradictory man, but the contradictory nation he helped found.

As we move into the early 19th century, there is an observed boom in industry, agriculture and expansion. With Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark expedition, the questions raised are, Why did Indigenous tribes help the Lewis and Clark group survive? How does American mythology present itself in historical interpretation and national memory? As populations grew, immigration increased and industry spread across Northern cities, our questions are, How did the cotton gin transform society? How did immigrants preserve their nationality in the U.S.? What work were women doing? What were work conditions like? How did economic shifts impact cultural shifts?

The questions surrounding the Civil War has filled up whole courses and volumes upon volumes of historical literature. But some questions include, Who really won the Civil War? Were the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments enforced properly? What changed after the Civil War? What did Connecticut do to help the cause? What were the varying beliefs among Republicans and Democrats? How did the justifications for the War, shift as time went on?