An exploration of Scott Kurashige’s groundbreaking historical research on the history of Los Angeles.

Scott Kurashige explores the social and political dynamic between Black and Japanese residents in Los Angeles from the beginning to mid-20th century in The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles. Kurashige reveals how the oppression of one race harmed the broader community. He explores the solidarities and tensions between the groups and in this, uncovers the intersectionality between races and class. Racial oppression was linked to white supremacy and patriarchy. White patriarchy is “othered” because it is the system that holds the most power. Kurashige provides examples of how Black and Japanese Americans interacted with said power through residential living, labor, gender, and political organization and ideology.

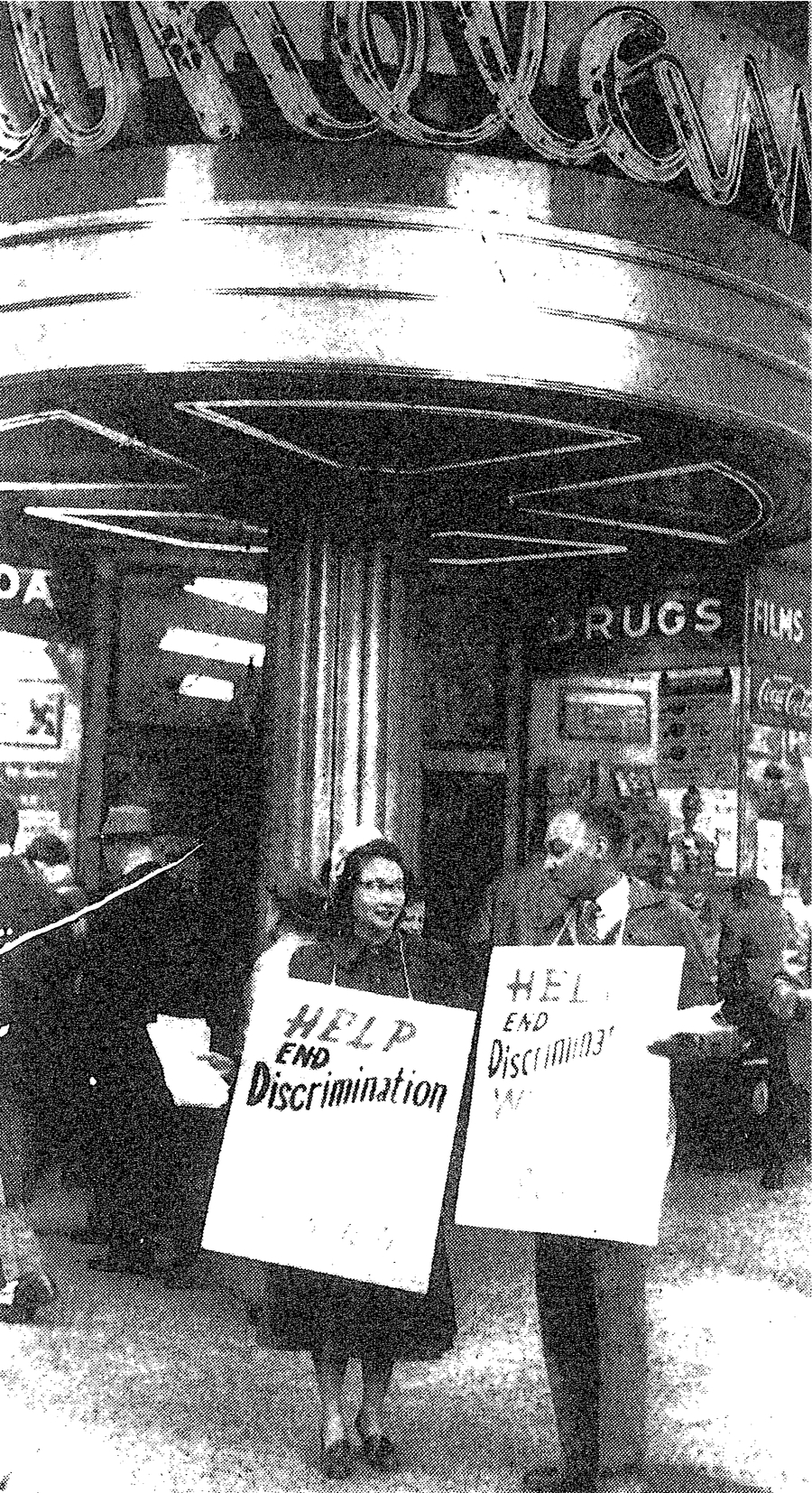

At the turn of the 20th century, Los Angeles was not the progressive cosmopolitan city it is today. In fact, the foundation of the city lies on racism. Films like Birth of a Nation, which was essentially white supremacist propaganda, paved the way for Hollywood to be a primary economic vehicle. This sentiment reflected the environment and geography of the area, pre-WWII. Black and Japanese Americans were confined to live in specific districts away from white families. “Racial restrictive covenants prohibiting nonwhites from inhabiting houses provided the crucial instrument to advance residential segregation during the interwar period…restrictive covenants, unlike racial zoning, were attached to specific privately owned properties and deemed to be the actions of individuals rather than the state.” As a result, Issei (Japanese immigrants), Nissei (first-generation Japanese-Americans) and Black residents were restricted to live on the eastside of L.A. This area would be known as Bronzeville or Little Tokyo, depending on who you were talking to. Congested and unsafe conditions made living among one another difficult. Despite that, Black and Japanese relations were generally not hostile as they saw one another in a similar boat. Both groups possessed an “entrepreneurial spirit,” and learned to rely on one another economically.

After the bombing at Pearl Harbour, anti-Japanese racism was everywhere and the threat of internment was looking like a reality. Reactions from African American leaders had mixed responses to this. Some flat out blamed the war on white racism and condemned Japanese extraction, while others saw it as an opportunity. During Japanese internment, Black development of Bronzeville flourished. When it ended and families returned to rebuild a life in Los Angeles, it completely shifted the dynamic of how the groups related to one another. They each blamed the other for not being vocal enough. Black residents accused Japanese of not standing up enough for civil rights struggles and Nissei mark African American silence during internment.

This is really big in terms of the conversation surrounding intersectionality. We see two groups- Black and Japanese Americans- forced to live in the same neighborhood as a result of white racism. In this they have a commonality, their race makes them vulnerable to systemic violence. In the moments that they found solidarity and encouraged unity and growth, efforts were pushed in a positive direction. At the time of Japanese internment, Black residents may have benefited to some degree, but that was quickly dissolved after the war. This indicates that the oppression of Japanese families, directly impacted the Black community. While they have overlapping, they also have divergences. For example, while the Japanese had internment, Black families had segregation. Once internment ended and reparations were distributed, discrimination of Issei and Nissei cooled. Black families, however, still had segregation. This is crucial to understanding how white systemic aggression handles itself; centering whiteness in power dynamic.

At the center of intersectional rhetoric is the study of gender. According to Kimberle Crenshaw, both feminism without anti-racism and anti-racism without feminism, reinforces white supremacy and patriarchy. Without a commitment to feminism, it reinforces interracial sexism against women of color. “She argues that Black women are frequently absent from analyses of either gender oppression or racism, since the former focuses primarily on the experiences of white women and the latter on Black men.” This helps us understand the heart of intersectional theory- black women, facing multiple oppressions in race, class, and gender gives us the concept of “interlocking oppressions” or “double jeopardy,” making them a more vulnerable group than white women or black men. Kurashige gives us some insight into Black women’s resilience in the Negro victory movement. Led by Charlotta Bass, women protested the Negro Victory Committee to offer them defense industry training classes. Upon winning that fight, Clayton Russell, another leader in the movement declared, “The future of democracy in the world and for the American Negro depends to a great extent on the role of Negro women during these war years and the responsibilities which they will accept.” As far as Japanese women, admittedly Kurashige doesn’t go into with as much detail. However he does touch upon the film, Sayonara, depicting the trope of white men fetishizing Japanese women as exotic, erotic prizes. White paternalism reinforced gender stereotypes and gave way to the feminization of the “model minority.”

As a result of white workers having an antagonistic relationship with workers that were people of color, Black and Japanese labor organizers found common ground in Communism. It was seen as the political party for “oppressed nationalities,” viewing the Soviet Union as a model government. During the 1930s, people of color embraced the American Communist Party (CPUSA) as a vehicle to push equity in civil rights and labor reform. They viewed white supremacy and capitalism to be synonymous, and in this time we see independant, multiracial groups form such as the Market Workers Union. After WWII, Communist organizing was severely targeted, with the rise of McCarthyism and the American Red Scare. Unions were forced to sign anti-communist pledges and even still FBI and CIA surveillance made organizing next to impossible. L.A.’s Communist party membership dropped by 90% during this time and this affected civil rights advancement. Negro victory leaders were targets of investigation and many saw their credibility driven into the ground. Groups like the NAACP break their alliances with CPUSA stating, “world communism is equal to the destruction of civil liberties.” Civil rights efforts for both Black and Japanese, had become fractured. Whether organizations were actually Communist or not, was irrelevant. They had become racial targets under the guise of politics.

The links between intersectionality and Communism are far and few at the moment, but they do exist. Marxism can be the single movement that connects intersecting groups against power structures and capitalist exploitation. For Karl Marx, one of the great political theorists that expounds on Socialist and Communist rhetoric, race, class and gender were concrete groups that intersected in various ways- and they coalesced in a revolutionary fashion. In the Communist Manifesto he makes the argument that capitalism was founded on Black slave labor: “Direct slavery is as much the pivot upon which our present-day industrialism turns are as machinery, credit, etc. Without slavery there would be no cotton, without cotton there would be no modern industry.” In his manuscript entitled, Capital he argues that capitalism has an element of genocidal character to it, working Africans to death and talks of a “slave revolution.” What is to be said about Marx in regards to social progress and equality, is that his lifelong quest, was to create a working class solidarity across racial lines. Class-reductionists would argue that intersectionality gets in the way of Marxist politics; they believe the real issue is class struggle and identity only muddies the water. However, ignoring the nuance of disadvantages that exist for certain groups and not others, does not lead to a unified, equitable proletariat.

By observing the structures of power that controls people in specific sociopolitical formations, we understand the intersectional dynamic at any given place and time. When power is looked at from the top down to the bottom up, we can dismantle its structures that impose selective vulnerability upon people. Through Kurashige’s analysis of Los Angeles at the turn of the 20th century, those power structures are explored and its impact on Black and Japanese Americans is apparent. Their interaction with those oppressive forces connected and divided, and by understanding their narrative, it gives way to insight on how to dismantle those power structures that exist today. “In order for all people to resist domination, all groups must work to dismantle systems everywhere that serve to constitute oppression.”

Sources:

Kurashige, Scott. The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles. Princeton , NJ : Princeton University Press, 2008. 21-27, 59-104-105.

Cho, Sumi, Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, and Leslie McCall. “Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis.” Signs Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2013. Accessed October 12, 2017. www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/669608.

Kimberlé Crenshaw – On Intersectionality – keynote – WOW 2016 SouthbankCentre – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DW4HLgYPlA.

Anderson, Kevin B. “Karl Marx and Intersectionality.” Logos a journal of modern society and culture. Accessed October 12, 2017. logosjournal.com/2015/anderson-marx.