In the early summer months of 2023, Janelle Monáe released her sixth album Age of Pleasure and for many including myself, it was the soundtrack of the season. Monáe is lauded for her Afrofuturist lyrics that speak truth to power- questioning political systems and ways of being, all layered under a catchy, danceable beat. In their most recent album, The Age of Pleasure, she departs from her ArchAndroid persona to create a world of pure joy and ecstasy. Monáe redefines post-2020 Pan-African sound by incorporating hip-hop, Afrobeat, jazz, reggae and Motown into their body of work and by doing so, she captures community and its sonic dimensions. Featuring Black matriarchs like Sister Nancy and Grace Jones and collaborating with Seun Kuti, the son of Nigerian revolutionary Fela Kuti, The Age of Pleasure is not only unapologetically Black and queer, it imagines what life would be like without white heteronormative patriarchy. This research positions Monáe’s latest work alongside Black feminist scholars who have imagined the possibilities of a world free from oppressive power structures and Black erotic creativity as a tool for transformation.

Monáe cultivates a post-Covid Pan-African sound and space to reimagine joy and pleasure as resistance, a response to an increasingly fascist reality. She imagines a world without white supremacy and hierarchy, a space that is beautiful, queer, femme and Black. Incorporating the writings of Audre Lorde, Jennifer Nash, and Saidiya Hartman, this analysis will illuminate the ways in which Monáe’s Age of Pleasure is part of a larger Black queer feminist philosophy of radical love and acceptance as a method of resistance. It works against a system designed to categorize and control bodies and the ways people express love and pleasure. Instead, Monáe imagines and creates for her listener, a more fluid, thriving world and asserts there is another way of being.

It is challenging to apply only one theoretical framework to The Age of Pleasure. Janelle Monáe draws upon so much inspiration in the short album that multiple theoretical analyses are necessary to fully capture the wisdom she is demonstrating in the most subtle, joyful ways. As a result, this research will analyze the tracks by incorporating Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: Erotic As Power;” Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality by Jennifer Nash; and Saidiya Hartman’s methodology in her book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, as frameworks of analysis. While every song in the fourteen-track album could be analyzed through a Black feminist lens, this research will only focus on the songs that were accompanied with a visual component. Janelle Monáe released three official music videos for songs “Float,” “Lipstick Lover,” and “Waterslide.” Each song will be examined through a Black feminist theoretical framework to identify how Age of Pleasure fits within a larger Black assertion of joy as resistance. In addition, delving into the imagery and themes Monáe explores, it illustrates the world-building she is sonically transferring into our consciousness; to remind us there is a more beautiful reality waiting for us if we choose to divest from the institutions that are no longer serving us.

Everyday People Collective and Monáe’s Inspiration

During the COVID-19 pandemic, much like many of us, Monáe was locked away in their home with very little to do but worry about present conditions. Her friends were involved with a group named the Everyday People Collective, an organization of Black and Brown people representing the entire African diaspora. They host events all over the world including Ghana, United States, Brazil, South Africa, Jamaica, and on and on. At these events, there is an emphasis on Pan-African joy and sound. According to their mission statement, Everyday People’s purpose “is to celebrate the creativity & diversity of black culture across the global diaspora.” Showcasing expressions of art, identity, thought, and community gathering, they endeavor to create respectful, joyful and proud spaces of belonging, inspiration and freedom.[1] A Los Angeles group was having difficulty securing a location to host their party because of the pandemic, so Monáe agreed to host the event at her home. As the party was occurring, Monáe observed the guests and realized they wanted to create music inspired by the collective. “I want to create music for these people, like this is Black joy, this is what we fight for.”[2] Exploring the fluidity of life, the album addresses trauma and experiencing joy as a healing modality. Janelle Monáe’s music is emblematic of navigating a world that was never designed for her, and in Age of Pleasure, she endeavors to build an alternative world that preserves community and free expression.

It is clear when one listens to Monáe’s music, that she is working with an archive despite asserting her own Afrofuturist spin and style. She draws on the musical inspiration of both men and women in her sound and imagery which includes Prince, Sun Ra, Fela Kuti, Jimi Hendrix, Grace Jones, David Bowie and Gladys Bentley. Creating a sacred place of fluidity was her mission and she devised a healing space for her listener, later bringing this energy on tour. Throughout the album she incorporates water imagery which will be examined more closely, but it is important to note the emergence of water as a common theme in Black women’s music today.

The meanings of these songs range from sacred femininity, to unapologetic sexual agency, to female ejaculation. In Cardi B’s breakout single “Bodak Yellow,” she melodically asserted her pussy feels like a lake and her man wants to swim with his face.[3] Similarly, the fall 2023 hit, “Water” by Tyla, asks her male subject to make her sweat, make her lose her breath, make her water.[4] In Solange’s “Almeda,” she lists off all the qualities of Black excellence and remarks that none of these things can be washed away by that Florida Water.[5] In Hoodoo and Santeria, Florida Water is a fragrant perfume that is used as a sort of holy water and spiritual cleanser.

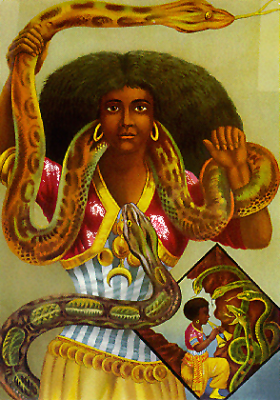

This convergence of sexuality and spirituality are also evoked in Monáe’s work. Age of Pleasure has a way of reminding the listener of the African deity Mami Wata, a venerated water spirit in West, Central and South Africa, as well as throughout the African-American diaspora. Sometimes male, sometimes female, Mami Wata allows her devotees to create their own reality, imagining themselves in their own visualization of her created world. In this imagined world, her devotees possess her sacred powers, satisfying their desires and manifestations in the physical world.[6]

While Monáe has not explicitly evoked Mami Wata in her explanation of the album, the parallels are evident to those familiar with the deity and Monáe’s nonbinary, pansexual identity. The use of water as a thematic image evokes a healing message, mending generational trauma associated with the element and with that, Monáe encourages us to embrace the flow and fluidity of life- much like the God(dess) Mami Wata themselves.

Historian Daphne Brooks situates Monáe’s “siren songs” alongside a larger Black diasporic tradition, “Monáe is the phonographic archive, the performing repository of her future, (post)-human self, the media(tor) who toggles between the discursive citationality of the notes and the multidimensional resonances of her embodied performances.”[7] Brooks argues that

Monáe captures Black history by the way of sound and lyrical genius. She catalogues and critiques the Black historical experience by way of sound. It’s reminiscent of the West African griot, relying on oral traditions to pass down information. In Monáe’s previous Afrofuturist albums, her alter-ego Cindi Mayweather returns from the future to lift humanity into higher consciousness. However, she contends with an authoritarian force that threatens her ability to express love, her agency, and ultimately her life. “We might think of her as situated in the midst of a long, complex, and heretofore unheralded history of Black women figuring themselves as records and recorders…who refuse the narrow sociocultural constructs assigned to Black women vocalists…”[8] Monáe challenges temporality in a way that blends Black history with the past and future. However, in Age of Pleasure, there is no time but the present.

In an interview with The Breakfast Club, Monáe explained to Charlemagne tha God, in her previous albums she was grappling with the world outside. Dirty Computer was a key example demonstrating her emotional response to political and social instability in the United States with the election of Donald Trump. Whereas, with Age of Pleasure, she is back from the future to have some fun. She’s too far ahead consciously and spiritually, so she waits for the rest of us to catch up. In the meantime, she is in a state of bliss and enjoying herself. In The Age of Pleasure, it is perpetually summer, there is a balance in all things and ego is abandoned. Like Lord Krishna and his Gopis, she multiplies her spiritual self to remind us there is an illusory nature to the barriers we put on ourselves.

“It’s the age of pleasure baby, it’s a movement, it’s not just me, you feel people wanting to, and I just gave myself permission. I just divested in certain systems and programming; and it’s like Why not? Why would I waste my Earth experience, scared to jump? Once you deal with that, you release your concerns and you give yourself permission; it’s a different world.” She informs her listeners that freedom is waiting for them and not to be scared, she will guide them, she comes in love and peace. Of course, she knows that there are “clickbait-able things” that will pull people in different directions but in this age of pleasure, there is an understanding that not everybody is not as evolved and we have to accept that, but Monáe reminds us not to get frustrated; “We have to give each other grace. It’s what I think about myself that determines my quality of life.”[9]

Float and Jennifer Nash’s “Love Politics”

According to Jennifer Nash in her book, Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality, Black feminism has a long history of engaging with love politics. Analyzing intersectional theory alongside love, Nash asserts the struggle for justice is a loving practice. Calling for mutual vulnerability and witnessing, she explains, “Black feminism pleas for love as a significant call for ordering the self and transcending the self and for moving beyond the limitations of selfhood.”[10] On the opening track of the album, “Float,” Monáe situates Age of Pleasure firmly in the Black feminist tradition of love politics. Refusing the boundaries between self and the other, she illuminates other possibilities for her listener.

Featuring Seun Kuti and Egypt 80, the son and musical band of the late godfather of Afrobeat, Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti, the album begins softly and slowly as the melody pulls the listener in. Janelle immediately asserts that this is going to be a different kind of album; “No, I’m not the same, uh-I think I done changed, yeah,” which cues the brasses and woodwinds to come forth and take us on a ride. Integrating hip hop beats, jazz, and Nigerian roots, Monáe and Kuti sonically define a Pan-African space. Monáe’s choice to feature Seun Kuti and Egypt 80 on the first (and longest) track of the album is deeply intentional to understanding Monáe’s love politics.

The son of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a famous women’s rights activist in Nigeria, Fela Kuti was a composer, musician, activist and Pan-Africanist in the twentieth century. Fela was the pioneer for Afrobeat, a fusion of sounds that capture the tenor of the African diaspora and the struggle for global anti-racism and human rights. His son Seun, is therefore part of an ancestral lineage rooted in radical anti-colonial politics. Seun Kuti was the youngest of Fela’s seven children and he expressed an interest in his father’s music at the age of nine. He performed with his father and his band until Fela’s unfortunate death in 1997. At the age of fourteen, Seun assumed the role as the leader of the Egypt 80 band and was given the radical political torch. Using sound to reflect the struggles and cultures of the West African region, Kuti and Egypt 80 bring political songwriting into the twenty-first century.[11]

Float’s radical love politics challenges binary thinking about love as well as the denunciation of self-loathing. “I used to walk into the room head down, I don’t walk, now I float,” Monáe illustrates her spiritual awakening and her surrender to a feeling of groundlessness. Demanding a radical reorientation to what is possible, Monáe describes polyamorous, pansexual love as an integral part of her love politics. “They said I was bi, yeah, baby I’m by a whole ‘nother coast. She stay in the hills, he stay in Atlanta, I paid for them both.”[12] According to Nash, collectivity is central to Black feminist love, transforming the personal into a struggle for justice and visibility. Refusing the boundaries between herself and her love politics, Monáe demands the listener reckon with the past and present. At the end of the track, the song fades to a toast:

“To the lives we lead (To the lives we lead)

To the dreams we chase (To the dreams we chase)

To the moments that we make (To the moments that we make)

And the fucked-up shit we can’t erase (And the fucked-up shit we can’t erase, woo!)”

The words of the toast echo a similar framework found in the Combahee River Collective statement, “A healthy love for ourselves, our sisters, and our community.”[13] The listener becomes privy to this moment of mutual vulnerability and witnessing the importance of love in this struggle for justice. This is made further evident in the official music video that was released for “Float.” Janelle Monáe does not appear in the video, instead, it features a collection of professional dancers moving in and out of the frame in a variety of urban settings, incorporating an array of dance styles found in the African diaspora. By visualizing the deep political nature of counter-culture performance, this music video exemplifies the love politics found in “Float.”

Waterslide and Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic”

In Audre Lorde’s The Erotic as Power she says, “There are many kinds of power, used and unused, acknowledged or otherwise. The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling.” In a patriarchal world, the erotic is seen as pornographic, suspicious, a threat to order, and is suppressed out of fear. In many ways, the erotic should be interpreted as dangerous; it is the power that incites transformation in the fight against oppression. It is through this resilience of the erotic, “the personification of love in all its aspects,”[14] that Monáe explores in “Waterslide.” Exploring self-love and radical rest, “Waterslide” uses the erotic to describe her relationship with her body to enact change.

Monáe opens the song boldly exclaiming, “If I could fuck me right here right now, I would do that (do that).” Once again incorporating the theme of water and swimming, Monáe explores masturbation, pansexuality, and unrepentant self-love. According to Lorde, dominant power attempts to distort the culture of the oppressed. In order to avoid change the oppressive systems corrupt our connection to the erotic. The stigma associated with masturbation and free love has long been associated by the dominant power as sexually deviant behavior. Instead, Monáe allows us to see that there is no shame in these practices of the erotic. This approach to life and its pleasures is liberating for many listeners, especially when there are very few songs devoted to Black self-love. The only one that comes to mind is Tweet’s 2002 one-hit wonder, “Oops oh my,” but nothing has come close since then. It seems trivial to assert that a playful song about masturbation could manifest in long-term systematic change. However, Lorde explains that the erotic empowers us and provides a framework to examining life in all its aspects. White heteronormative patriarchy has taught us to fear our desires, Monáe reminds us it doesn’t have to be this way. “My level of freedom, Our level of freedom will always trigger somebody who has not decided that they are ready to get free.”[15]

Lipstick Lover and Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives

Saidiya Hartman’s creative and scholarly writing is particularly relevant to the images and themes explored in Janelle Monáe’s music. In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Hartman provides a theoretical framework for the struggle to create beautiful autonomous lives. In her work she explores the “radical imagination and wayward practices”[16] of women creating their own narratives. The effort to recover open rebellion in the archive, Hartman examines the lives of women who would have been described as criminal, deviant and wayward. Similarly, Monáe imagines a utopian paradise in “Lipstick Lover,” where there is open intimacy outside of marriage, lesbian love and Black joy.

The downtempo reggae track is represented at a pool party in the music video, not terribly different from the aesthetic observed in “Waterslide.” However, the pool party occasionally cuts to a dark room where Monáe alternates between being in a bathtub with her love interest to smoking a blunt with an older woman. In these moments we observe Monáe in subversive space, in the shadows she explores her passions and curiosities. Much like Hartman’s writings, Monáe captures the intimate chronicle of Black feminist radicalism. While on its surface it seems ordinary, it is a narrative that has long been overlooked. By capturing it sonically, Monáe personifies queer waywardness in all its beauty. Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments focuses on the lives of women from 1890 to 1935, but this only exemplifies the timelessness of the themes addressed. Black queer love has existed for as long as people have been homo sapiens. The white, cisgender, patriarchal systems that attempt to render it invisible are no match for Hartman and Monáe’s imagination; threading the needle between the abstract and physical realities.

Age of Pleasure Live Performances

When asked why the album is so short, Janelle Monáe explained she wanted to give her listeners just enough of a taste that they’d want to play it again and again.[17] That very well may be true, but the reality is that many songs have gotten shorter in duration to be usable on the social media platform, TikTok.[18] Any song over 3:15, is not the best format for app users and for Age of Pleasure, the only song that’s over three minutes is “Float,” clocking in at 3:59. As mentioned previously, Monáe only released three music videos for Age of Pleasure; a large difference compared to the forty-eight minute Emotion Picture she released for Dirty Computer. I believe the reason for this is because Monáe for Age of Pleasure, she had focused her energy on the nationwide live tour. The North American tour ran from August 30, to October 18, 2023. While I did not have the honor of attending her Age of Pleasure tour, I was able to live vicariously through the endless posts on Instagram that chronicled the journey. As concert-goers arrived into venues, they were immersed in a space that was akin to a spiritual temple. On stage, verbal messages were written to remind people why they were there. “One day we all woke up and realized that we are even more than what the world told us we are,” and “Pleasure is safe, pleasure is affirmation, pleasure is consent, pleasure is an abundant resource.”[19] She wowed her audiences with a variety of costume changes, and dance numbers, performing tracks throughout her discography. In some cities, she even invited members of the crowd to join her onstage to dance and twerk; the world-building she set for her album did not simply live in the abstract, she actualized this vision throughout the United States.

Further, her performance at BET’s Soul Train Awards was one to remember. In addition to winning the Spirit of Soul award, Monáe performed a few tracks from the album including “Float” and “Champagne Shit.” At the end of her performance of “Float,” she told the audience to raise their glasses and she made a toast, much like how the song on the album ends in a call-and-response. However, she slightly tweaked the words of the toast to situate it very much in the present. She said, “to the lives we lead, to the dreams we chase, to the moments we gon’ make, and to the people they can’t erase! They can’t erase us, they cannot!”[20] Donned head to toe in a flower crown and dress, a possible nod to the 2019 folk horror film Midsommar, Monáe asks us to smile through the pain, share beauty with our communities, and assert Black queer visibility because it is a divine right. We may not be able to erase the pain of our ancestors, the epigenetic trauma, but we can find joy in the smallest of moments. A shared meal, a steady beat that calms your heart, and the sacred love that exists within. A love that is beyond the binary illusion that exists in cisgender white patriarchal systems.

New Realities, Futures, and Possibilities

The Age of Pleasure certainly is a departure from Janelle Monáe’s usual Afrofuturist, speculative fiction style. She places the temporality of pleasure in the here and now, building a bridge between possible futures and what is within our reach. The entirety of the album engages in world-building and imagines a space where all of our wildest dreams can come true, if we’re ready to surrender to the tide. Jennifer Nash’s love politics helps us understand the collaboration between Seun Kuti and Egypt 80 as more than a feature. Kuti and Monáe are part of a larger ancestral tradition of Black radical politics and they encapsulate self and community love in all its splendor. Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic” situates “Waterslide” in the powerful erotic, reveling in indulgent self-touch; spending the day loving oneself and the transformation that results from the time well-spent. Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments interweaves the narratives of sexually free women to illustrate the revolutionary struggle of radical sovereignty. This is a similar framework Monáe models throughout the entirety of the album, but particularly noteworthy in “Lipstick Lover.” Exploring her nonbinary, polyamorous identity and observing her work alongside the contributions of Black men and women, Janelle Monáe’s 2023 album is a Pan-African love note and a sonic tool for self-determination.

[1] “About Us,” Everyday People Collective, 2023, accessed November 22, 2023, https://www.everydayppl.nyc/about#:~:text=Our%20mission%20is%20to%20celebrate,freedom%2C%20connection%2C%20and%20belonging.

[2] Monáe, Janelle, “How Janelle Monae Created ‘Float,’” Muso AI, YouTube, accessed October 23, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/shorts/JG4_emawaj0.

[3] Cardi B, “Bodak Yellow [Official Music Video],” YouTube, June 24, 2017, accessed December 9, 2023, https://youtu.be/PEGccV-NOm8?si=5XpSiR0mR7mW5S-z.

[4] Tyla, “Water [Official Music Video], YouTube, October 6, 2023, accessed December 9, 2023, https://youtu.be/XoiOOiuH8iI?si=u8G47TkCMTRZvFOP.

[5] Knowles, Solange, “Almeda (Official Video),” YouTube, March 7, 2019, accessed December 9, 2023, https://youtu.be/6giKIu5jUvA?si=otYajPyJlRDmddlb.

[6] Drewal, Henry John, “Performing the Other: Mami Wata Worship in Africa,”TDR, 1988, Vol. 32, No. 2: pg. 160–185.

[7] Brooks, Daphne, Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021), 118.

[8] Brooks, Daphne, 122.

[9] “Janelle Monáe On Bodily Autonomy, Non-Binary Identity, The Age Of Pleasure + More,” Breakfast Club Power 105.1, YouTube, June 9, 2023, accessed October 5, 2023, https://youtu.be/gf5jrx78gF8?si=jOd3HsUTniv7MnGx.

[10] Nash, Jennifer, Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality, (United Kingdom: Duke University Press, 2018.), 111-131.

[11] Kuti, Seun, “About Seun Kuti,” Personal website, 2022, accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.seunkuti.net/about.

[12] Monáe, Janelle, Seun Kuti and Egypt 80, “Float,” Track 1, The Age of Pleasure, WondaLand Records, 2023, digital.

[13] The Combahee River Collective Statement, United States, 2015, Web Archive, https://www.loc.gov/item/lcwaN0028151/.

[14] Lorde, Audre, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” reprinted in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde, (Pennsylvania: Crossing Press,1984), 1.

[15] Breakfast Club Power 105.1, YouTube, June 9, 2023, https://youtu.be/gf5jrx78gF8?si=jOd3HsUTniv7MnGx.

[16] Hartman, Saidiya, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019), 1-2.

[17] Breakfast Club Power 105.1, YouTube, June 9, 2023, https://youtu.be/gf5jrx78gF8?si=jOd3HsUTniv7MnGx.

[18] Wright, Danny, “Pop Songs Really Are Shorter Than Ever Now,” Vice, April 13, 2023, accessed December 9, 2023, https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjv8pq/pop-songs-shorter-than-ever.

[19] Blotevogel, Kimberly, (@bitchburgerbibliophile) September 14, 2023, Instagram.

[20] “Keke Palmer Shakes Her Hips To Janelle Monáe’s Energetic Performance | Soul Train Awards ‘23,” BETNetworks, November 26, 2023, accessed November 27, 2023, https://youtu.be/saHkEH1MxJI?si=3-MXcsxqVDjyure6.