This article originally appeared on ConnecticutHistory.org, a program of Connecticut Humanities.

In the 20th century, there were monumental advancements in psychology and mental health research that coincided with unprecedented growth of LGBTQ+ visibility. The simultaneous development of accepted mental health practices and LGBTQ+ visibility over the decades offers a chance to examine how psychological research contributed to the discrimination of LGBTQ+ individuals and communities. Through examination, it becomes clear that there were ways in which mental health institutions and research both helped and hindered the health of LGBTQ+ people throughout the 20th century.

Early 20th Century: Eugenics in Mental Health

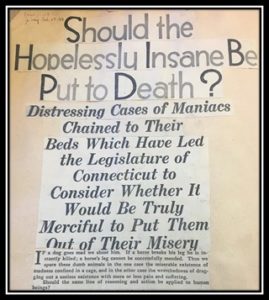

The eugenics movement emerged in the late 1800s and became a dominant scientific theory until the 1940s. A term coined by Sir Francis Galton in 1883, “eugenics” is the study of how to control and arrange reproduction to “breed” or “breed out” heritable characteristics of human genes that are deemed desirable or undesirable. Racist, classist, ableist, and homophobic ideologies of the early 20th century largely determined the desirability of specific traits.

In 1926, Yale economics professor Irving Fisher founded the American Eugenics Society and The Race Betterment Foundation. In addition to Fisher, Robert Yerkes was a professor in psychobiology and created mass aptitude testing. The tests claimed to measure cognitive capacity and moral standing. Policymakers, healthcare providers, academics, and others used the mass aptitude tests to justify forced sterilizations—to prevent those with undesirable cognitive abilities and moral standing to pass those traits on to their children. At the time, officials often characterized any sexual or gender identities that deviated from heterosexual or cis-gender as mental illnesses and therefore “undesirable.”

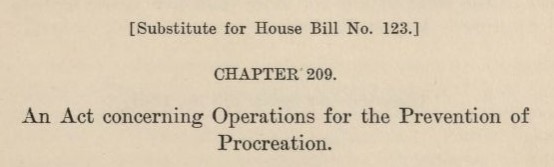

In 1909, the Connecticut General Assembly passed the law, An Act Concerning Operations for the Prevention of Procreation. It was one of the first sterilization laws in the country, second only to Indiana. It was not until the 1920s, however, that officials fully implemented the law. Between 1909 and 1963, Connecticut sterilized approximately 557 people—92 percent were women—with 74 percent identified as mentally ill and 26 percent considered “mentally deficient.” While much of the data in Connecticut is unclear, in Indiana, Dr. Harry Sharp recorded 1/3 of the sterilized men receiving their vasectomies due to “sodomy,” a common catch-all term at the time for same-sex interactions. In the 20th century, every state had sodomy laws, which outlawed a list of sex acts, but officials primarily used them to target homosexual people. Connecticut did not repeal its sodomy law until 1971.

After Nazi Germany’s use of eugenics helped lead to the Holocaust, the movement lost its popularity with much of the public. Many eugenic practices, however, did not disappear. While it is now rejected as an accepted theory in science, eugenics-based assumptions survived in anti-gay marriage rhetoric and continue to influence institutional policies when it comes to allowing LGBTQ+ people to adopt children.

Mid-20th Century: Pathologizing Gender and Sexual Identity

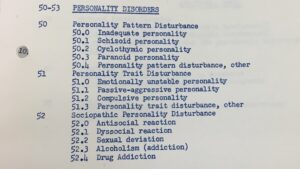

During the mid-20th century—using Freudian analysis and new therapies—scientists and doctors outlined new ways of defining sexual and gender identity as a personality disorder. The earliest publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance.

In 1951, Connecticut Department of Mental Health (DHMAS) classified “sexual deviation” in the same category of mental illness as antisocial behavior, drug addiction, and alcoholism. That same year, West Hartford community member Aaron G. Cohen gave recommendations to Governor John Lodge to create a separate department in the state’s mental hospitals for sex cases. He proposed specialized treatment to “absorb these unfortunates.”

Five years later, DHMAS went further, outlining the treatment of “sexual deviation” in children. They proposed 24-hour supervision in a controlled living situation for children exhibiting “sexual misbehavior,” which they defined as “children who strongly wish to be the opposite sex, a compulsion to masturbate or other symptoms related to fears or guilt about sexuality.” They focused on imposing outer controls to ensure the child assimilated into the community as a “normal individual.” Over 60 years later, in 2017, Connecticut finally banned all forms of conversion therapy for use on minors.

Late 20th Century: Compassionate Care and Empathy

Influenced by the civil rights movement, the Stonewall Riots in 1969 triggered a national push to bring LGBTQ+ visibility into the mainstream. Community members began to form networks of support in nonprofits, private organizations, and activist spaces to promote LGBTQ+ mental health.

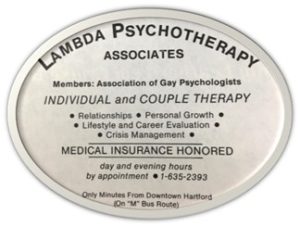

Starting in 1982, gay publications such as Metroline magazine provided Connecticut LGBTQ+ residents with a directory of mental health professionals that specialized in the community’s needs, including counseling and addiction treatment. The magazine also ran a column called “Balancing the Imbalances” written by counselor Rob Gould. It focused on addressing internalized homophobia, mental health awareness, and developments in the field of psychology that fostered empathy and acceptance.

In the 1990s, youth mentorship programs such as True Colors were founded to support young people in the state. In addition, hospitals such as The Institute of Living also implemented LGBTQ+ treatment programs to cater to the unique needs of the community.

While there have been revolutionary advances in the treatment of LGBTQ+ mental health in the last hundred years, gender identity and expression are still in the DSM-5 (the standard classification of mental disorders) and labeled as “gender dysphoria.” In addition, in modern psychological studies, transgender research is still severely lacking, as oftentimes trans identity is excluded from study samples or data because it is considered an outlier. The development of mental health treatments and the growth in social acceptability of LGBTQ+ identities resulted in drastically different approaches to treatment from the beginning of the 20th century to the end. Addressing discrimination and other shortcomings found in modern practices may very well help shape mental health research in the next hundred years.