The New York Draft Riots in 1863 almost destabilized the city and was one of the most violent events in the North during the Civil War.

It was 3 o’clock on July 15, 1863 in New York City. Mrs. Statts arrived two days prior from Philadelphia to visit her teenage son, William Henry Nichols. A mob of Irishmen gathered outside of Nichols’ residence and began to shout racial slurs, throwing stones and bricks at the building. A wave of panic washed over her as she glanced into the other room and looked at a bedridden woman, having just given birth three days prior. She broke her gaze from the woman when she heard the mob breaking down the front door. The door burst open and the men rushed to the bed where the woman was lying and ripped her clothes off. Statts grabbed her son and ran into the basement where she found ten other women and children from the building, huddled together in a corner, cowering in fear. Mrs. Statts looked outside the window facing the backyard and witnessed the mob hurl the three-day old infant out a window into the yard, killing them instantly.

Knowing they were hiding in the basement, the mob broke the water pipes with their axes and the room began to flood. Fearing they would drown if they stayed, Mrs. Statts grabbed her son’s hand and fled for their lives out to the back yard. She ran past the dead body of the infant, to hop a fence. Overwhelmed by her fear, Statts fainted and her son jumped down to retrieve her, but it was too late, the mob had caught up to them. Nichols pleaded for them to spare his mother as they snatched his arms and bashed his head with a crowbar, he died two days later in the hospital. After she learned her husband had fled to Rahway, was turned away at a police station, and beaten by yet another mob, she began to wander by foot back to Philadelphia. When she reached Jersey City, a man by the name of Arthur Lynch found her and took Statts back to his home, where he and his wife nursed her back to health for two weeks.

Mrs. Statts’ personal account of the horror and loss she witnessed is just one of hundreds of reports of Black citizens being brutalized by Irish laborers during the New York draft riots. The Conscription Act, the first wartime draft in American history, had a provision that allowed those who could pay $300 to avoid having to fight in the Civil War. On Monday July 13th, an estimate of anywhere between five to fifteen thousand Irish people flooded the streets of New York in resistance of the draft. The draft office was burned down and from there, the mob became uncontrollable and sustained its violence until late Thursday, July 16th. Black people were especially a target, nowhere in the city was safe to escape the mob. Homes were destroyed and people were driven into the streets to be beaten and lynched. While the draft was temporarily suspended in New York, order was restored by the military and the draft proceeded, by order of President Lincoln.

The Black community targeted in the riots had nothing to do with the issue of the draft, the mob’s brutality towards them, demands an answer to the question of their motivations. The answer lies in those who held the most power. The oppressive forces that discriminated against Irish and Black people made the conditions possible for such an event to occur. While the Irish experience of the United States is nothing like what Black people had ever faced, the intersections of Irish and Black oppression reinforced one another and resulted in the brutality of the riots. Systemic racism coupled with the control and influence of political parties, divided the labor class into racial hierarchies. According to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, intersectionality is “the idea that multiple oppressions reinforce each other to create new categories of suffering.” By applying intersectional theory as a form of critical inquiry to the draft riots, it enables us to understand the “life and behavior rooted in the experiences and struggles of disenfranchised people.”

My research does not go against prior research but rather reinforces it. Integrating intersectional theory with Civil War and labor history provides the key to understanding the source of the draft riots. It lies in the xenophobia and nativism the Irish were subjected to, compounded with racism towards Black people and the control and influence of the Democratic Party.

American Nativism in the 19th century

Ireland’s potato famine became a humanitarian crisis in the 1840s as two million Irish refugees desperately came to the United States. This influx of Irish immigrants in such a short span of time incited backlash from native-born Americans. German-Americans condemned the amalgamation of English and Germans with the Irish. They stressed the preservation of bloodline, asserting English and Germans were cousins and the Irish were of a different race. They used the draft riots as an example of why they needed to preserve their nationalities.

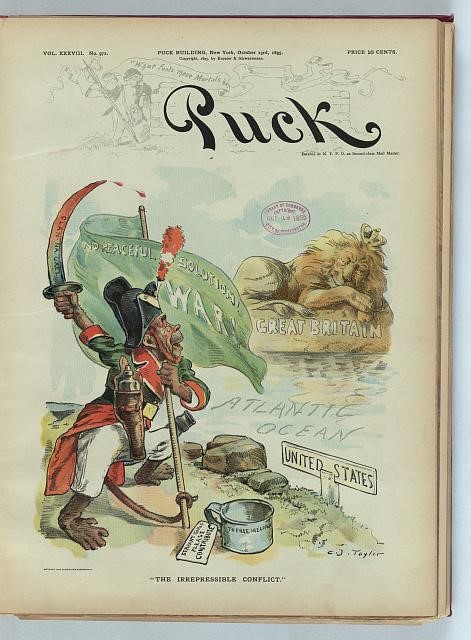

An image published by Puck magazine entitled “The Irrepressible Conflict,” displays a monkey in an Irish military uniform on the U.S shore looking at a lion labelled as “Great Britain.” At the monkey’s feet is a cup labelled “To Free Ireland” with a tag that says, “Servant Girls Please Contribute.” This depiction of the Irish as animals, primitive and begging for money from their female counterpart was meant to dehumanize and emasculate Irish men. It is also an example of how the Irish were compared to Black people, justifying that while they were white, they represented another race to the Anglo-Saxons.

The root of Irish discrimination was in racism towards Black people. Comparisons and insults of the Irish and African Americans were explicitly similar. Some suggested the Irish were a “dark race,” speculating if they were of African ancestry. A Whig aristocrat, George Templeton Strong once said, “to be called an ‘Irishman’ had come to be nearly as great an insult as to be called a ‘nigger.’” They were compared to one another because of environment and class. Both lived in the same neighborhoods such as the infamous Five Points, they worked the same jobs, and both had been wrenched from their homes. The key distinction, however, is Black people had no choice in the leaving of their home country; being kidnapped, subject to hundreds of years of brutality and chattel slavery. While the Irish famine was more of an attempted genocide as the British starved them out of their homes, they did ultimately have an opportunity to escape to the Americas. They were able to become naturalized citizens, participate in national politics, and move about the country without fear of being captured and put into slavery.

The Irish Democrats

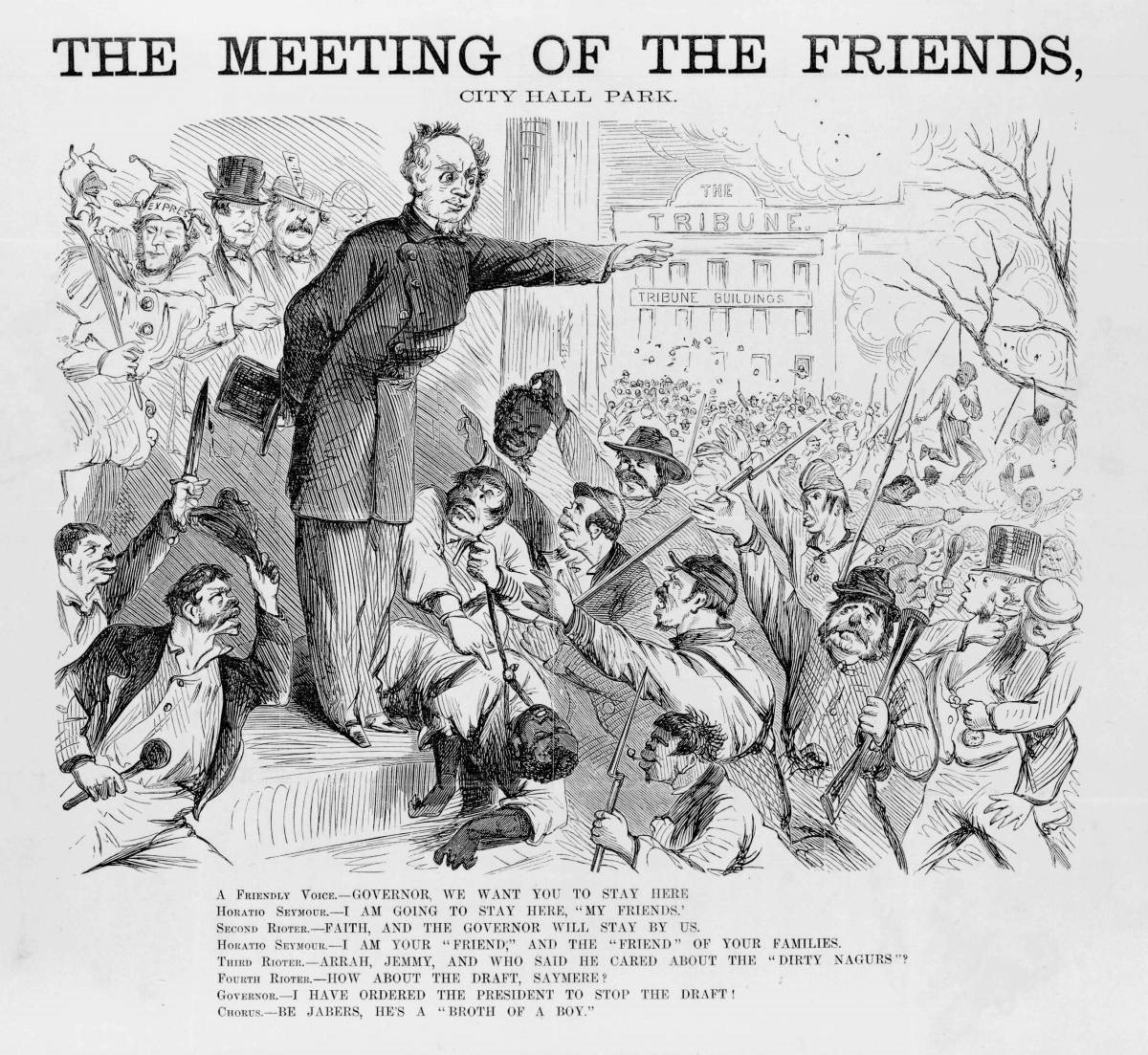

The Irish were keenly aware of this privilege, capitalized on their whiteness and became very involved in the political process. There were two groups that would not question their race, the Catholic Church and the Democratic Party. They associated nativism with the Republican Party and backed the Northern Democratic candidate Stephen Douglas in the 1860 presidential election. However, they also joined the Union forces to claim American identity and have a place within the republic. Despite their enlistment in the Union army, Republicans had growing anxieties of the Irish at the ballot and labelled them as part of the Copperhead Democrats, named as such because they were seen as venomous snakes. The Copperheads presented themselves as a peaceful, anti-war, diplomatic faction of the Democratic Party. Abolitionists rightly viewed the Copperhead Democrats and ‘radical Democrats’ of the South to be one in the same. Evidence of this assertion is seen with Democratic New York Governor, Horatio Seymour who had condemned the draft two days prior to the riots, instigating Irish Democrats.

The Irish used the Democratic Party to rise to power, Thomas Kinsella being a prime example. Kinsella was an Irish immigrant, U.S. Representative from New York and an editor of The Brooklyn Eagle and Daily Eagle newspapers. He used his newspapers to further the Democratic agenda and labelled the draft riots, “The Anti-Negro Riots.” He acknowledged the riots were “lawless attacks,” and showed some sympathy towards the Black community saying there is no manhood in the white man attacking defenseless Black people on the street. However, he also added, “The real friend of the colored man never would have placed him in a position where he would come in immediate antagonism with the white and superior race.” He urged Democrats to fight at the ballot box, spreading a message of nonviolence and simultaneous subordination of Black people; classic Copperhead rhetoric.

While nine-tenths of the rioters were Irish Catholic, not all Irish Catholics were Democrats. Irish Republicans blamed the riots on Democratic propaganda and the ability to recruit people “from the lowest and most degraded social class.” The Democratic Party’s unabashed racism and platform of white supremacy pandered to the Irish in the Northeast; it alleviated the stress of their poverty, promising upward mobility and using their whiteness to get it.

The Southern political strategy was to uphold states’ rights, clinging to their anti-Federalist rhetoric of limited government. They defended the ability to hold slaves was written directly into the Constitution, emancipation was an infringement of their civil rights and abolitionism was the true cause of the war. To them, the Constitution and nation only belonged to those who were white. In the Democratic Anti-Abolition State Rights Association of the City of New York’s constitution, they made the case for upholding Jeffersonian democracy and white supremacy. They explicitly stated that the U.S. “…was made on the white basis, by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever, and that wherever the black and white races come in contact, the natural or normal condition of the former is a state of subordination and servitude.” That’s not to say the Republican Party was abolitionist; the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 reflected military considerations and the party’s stand for free labor as opposed to slave labor. In their own economic self-interests, the Irish vehemently opposed emancipation, fearing freed Black people would flood the labor market, depriving them of jobs. This was obviously a myth, the Irish had more labor competition with German workers than African Americans but they focused their animosity towards them because Black people were less likely to strike back, either politically or through direct action.

Anti-Blackness in New York

The draft riots themselves were a prime example of the racism in New York, a physical manifestation of anti-Black sentiment. Without cause or provocation, Black people were brutalized and driven out of the city. Following the riots, forty percent of the Black population fled New York, an estimated five-thousand men, women and children were refugees. Some went to Brooklyn and Long Island, others retreated to swamps along the Jersey shore. The Black population declined by twenty percent two years after the riots to below 10,000, compared to 12,500 in 1860. The draft riots commenced an exodus of African Americans leaving the City and it lasted nearly a decade.

The most notable accounts of violence during the riots included the murder of Abraham Franklin, a man who was beaten unconscious, had his throat slit and then hung on a lamppost for hours. Another important account was the burning of The Colored Orphan Asylum. On Monday July 13th, four hundred men stormed into the orphanage, looting and destroying furniture and ultimately burning down the building. At the same time the mob was storming through the front door, the Matron and Superintendent were quietly evacuating the children out the back of the building and guiding them to the nearby police station. The children remained at the station house until Thursday, 230 children between the ages of 4 and 12.

Weeks and months after the draft riots also posed a serious issue for those who chose to remain in the city. Landlords evicted Black people from their tenements after the riots out of fear the mob would eventually return. Employers also terminated Black laborers to appease to their white workers and prevent further conflict. The Common Council had set aside millions of dollars to pay for conscripts to allow poor whites to avoid the draft, but nothing was given to African Americans by the government to repay for damages. As a result, efforts were made to restore order and provide financial relief to the New York Black community by private donors. The Merchants Committee for the Relief of Colored People Suffering from the Riots in the City of New York allocated a total of $40,779 to provide relief to those who lost family members, suffered from insanity resulting from the riots homelessness or job loss. Publications like The Anglo-African encouraged Black residents to return to their communities. Despite fervent condemnation of the riots and efforts to provide relief, Merchants Committee Chairman John McKenzie revealed his perception of the Black community being helpless. In his address to Black leaders who had organized a spontaneous meeting to thank the Committee for their work, McKenzie’s response reinforces the notion that Black people were never seen as equals, even to the whites that were supposedly “on their side.” This is most evident when McKenzie says, “Go where we may the black man does not escape us…what shall be done with the Negro?” Zion’s Herald and Wesleyan Journal, a Progressive Christian magazine, argued that there was no “Negro Problem” besides keeping them in bondage. They denounced colonization in Liberia as a solution and advocated for giving African Americans access to education and the opportunity to vote, defending that there was no greater patriot to walk American soil. Conversely, they also made the assertion that the Irish were extremely problematic; disloyal, aggressive and drunkards. The publication argued that Blacks were more deserving of a vote than Irish immigrants. While the publication claimed a platform of social justice for oppressed and disenfranchised groups, they alienated Irish people, most likely because of Catholicism being counter to their evangelical agenda.

Conclusions

Intersectionality reveals how white supremacy’s power was diffused through the overlapping and diverging identities of the Irish and African Americans. Both populations were subjected to low-wages, labor-intensive jobs and varying degrees of discrimination. By stoking racial animus within the Irish community towards Blacks, it facilitated the brutality that occurred. It also affirms the social hierarchies that existed within these subjugated groups. Addressing Civil War politics in this way sheds light on how institutional structures selectively ordained vulnerability upon certain identities. It is important to observe the significance of politics shaping the way people in a specific time and geographic space are organized. Intersectionality speaks to contemporary issues traditionally, but by applying it to a historical context such as the draft riots, it illuminates how intersectionality is embedded in American society and evolves over time.