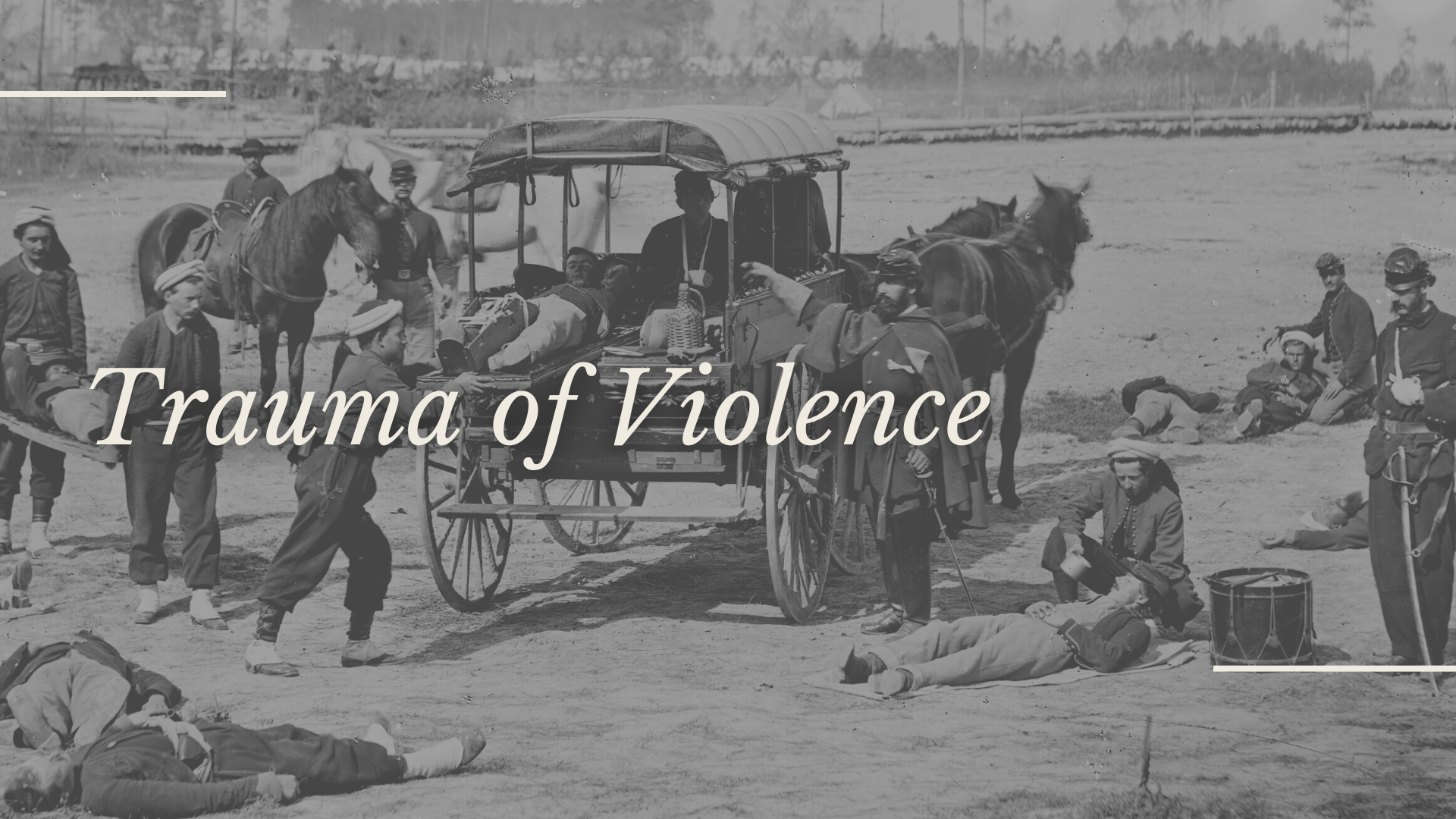

Union soldiers survived one of the most gruesome, violent events in documented history. What’s striking about their experience is the majority of men who served were completely average people, not trained combatants. For all intents and purposes, most Federal soldiers in the Civil War were temporary volunteers; young men who left their family farms or scholarly pursuits to join the Union cause. They had limited understanding of war and lacked the skills to carry out tactical discipline and combat. Some men enlisted to avoid legal or personal troubles at home but quickly regretted their decision once they witnessed the risks of war, firsthand. Regardless of their reasons to join, soldiers possessed a commonality: they were inexperienced.

They learned basic technicalities such as weapon handling and moving in and out of formations but received little to no instruction on actual combat skills. For the average soldier, they had no exposure to the realities of battlefield fighting until they were thrust into it directly. Everything they learned from training drills was deemed useless once the fighting actually started. The terrain of the South and displacement from home proved an additional challenge. Soldiers never learned how to deal with humidity and the rugged, heavily wooded country. The disruption of routines and abrupt transition into the abysmal structure of camp life, also meant the social boundaries of acceptable behavior dissipated.

Soldiers also faced disease, which turned out to be a bigger killer than Confederate enemy forces. According to historian Allen C. Guelzo, “For every soldier who died in battle, another two died of disease in camp.” Modern historians estimate more than ten percent of the Union army were killed from maladies. Men recruited into the war had to engage in domestic forms of self-care that would have been left to their wives or mothers’ responsibilities back home. Many soldiers were unable to make this adjustment and did not have proper clothing, hygiene or nutrition. Additionally, Northerners had a particularly difficult time adjusting to the south; the drastic ecological differences made them vulnerable to infection.

They went long periods of time without washing their clothes which made them susceptible to infestations of fleas, ticks, lice and other blood-sucking pests. Some disease was self-inflicted as soldiers contaminated their water sources with latrines and improper dumping of trash and waste. This practice attracted vermin and diseases like dysentery, cholera, and typhoid fever. Doctors, who often prescribed soldier’s alcohol and opium-based painkillers, exacerbated issues.

Widespread addiction and withdrawal symptoms such as mental illness and anxiety were exhibited by soldiers. Civil War medicine wasn’t equipped to deal with the wounds or trauma inflicted by the weaponry of the era and it wasn’t until after the turn of the century that surgery would evolve to properly treat gunshot wounds. At this time, the only solution was amputation, which horrified soldiers and doctors alike. Unable to withstand the conditions of war, more than 200,000 Union soldiers deserted the front.[1]

For those that remained, Union troops displaced from their homes did not have access to mental health treatment even if they wanted to seek it out. Thus, soldiers both relied on each other, and the letters written home to family and friends, to cope with the violence and trauma of the Civil War. Soldiers sent letters to their parents, siblings, children and wives to process the reality they faced. They connected to their networks of kinship as a means to cope with the trauma of violence, illness, and loneliness. Their letters took the unspeakable and put it to words. Applying a modern understanding of trauma and writing as a coping mechanism provides a more thorough analysis of Connecticut soldiers’ narratives and the effect the Civil War had on their physical and mental well-being.

Additionally, examining the letters through this method attempts to provide a form of historical justice. Judith Herman asserted, “The systematic study of psychological trauma therefore depends on the support of a political movement… In the absence of strong political movements for human rights, the active process of bearing witness inevitably gives way to the active process of forgetting.”[2] It is necessary in this historical inquiry to approach the sources with empathy and remember the soldiers were young men, sacrificed for a political war. If they managed to survive, Civil War veterans never fully received the compassion and care they needed in the years following. Exploring trauma narratives of Connecticut Civil War soldiers unveils the intricacies of agony and the lines of communication used to grapple with it.

When documenting Union soldier’s experience of the Civil War, one question pervades, how did they cope with the psychological trauma they endured throughout the duration of the war? This research finds the answer lies in the words recorded by the soldiers themselves. Examining Connecticut soldiers’ letters and interpreting the language they used to describe the traumatic events they lived through, reveals the complex nature of war and the harmful psychological effects it has on generations of young men. Shedding light on their experiences in this manner identifies the historical features of trauma; the methods people deployed throughout time to process and cope with the reality of war.

Trauma is part of the human experience and in many ways, shaped and developed our species. It is the defense reaction that helps to warn and protect against danger, but it can also trigger longstanding emotional and physical responses. However, the recognition of trauma and its effects are a relatively recent development. Psychological methodology and treatment associated with trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) did not gain traction until the post-Vietnam War era. When one considers the limited support and resources available, there is a deeper understanding of the struggles of Civil War soldiers.

Throughout the Civil War, soldiers wrote letters for multiple purposes. For one, writing home was essential for requesting personal supplies like food, clothing, liquor and money. According to historian Kathryn Shively Meier, letter-writing was most valuable for supporting soldiers’ mental health. “Correspondence fostered bravery and steadfastness in the face of environmental adversity, as no soldier wished to appear a coward to his family, and served as continual links to love and family care they remembered from home…Letters were physical talismans that loved ones had touched, providing comfort for soldiers’ darkest moments alone in their tents.” For some, it was validating to write to their beloved, providing an indication of the challenges they were facing. The letters and other ephemera sent from home were some of the few things they could carry along with them as small physical reminders that they were supported and loved.[3]

While language falls short to fully express what a survivor experienced, the recorded testimony provides a space for witnessing the hollow strain. By having a listening audience in the recipient of the letter, the writer experiences catharsis and attempts to gain closure. Trauma can transmit itself through language and literary means. According to Cathy Caruth, to be traumatized is to be “possessed by an image or an event,” and that traumatized people “carry an impossible history within them, or they become themselves the symptom of a history that they cannot entirely possess.”[4] The person does not hold the memories of the past, rather, the memories hold them. Therefore, the act of letter-writing in this instance, was an attempt at exorcising oneself.

Timothy Richardson’s study on writing and trauma illuminates the connection between experiencing traumatic events and the human impulse to transcribe the memory. Richardson’s philosophical analysis provides a framework for examining Civil War letters. In his view, people communicate their trauma through writing constantly, other people read it and interpret it for meaning throughout history. However, Richardson clarifies, “…the analyst is less interested in what words are proffered by the analysand than in those spaces between the words.”[5] This is essential to remember when examining the letters sent by Connecticut soldiers because while identifying their experiences with trauma, the words they used were sometimes not as vital as the spaces between those descriptions.

Reading between the lines and tracing the contours of these gaps identifies what Richardson defines as, “not spoken but what is nonetheless spoken about.” Evidence of trauma is found within the soldiers’ erratic speech, hastened rhythm and run-on sentences, constant and abrupt subject changes and frenzied handwriting. Oftentimes, soldiers sandwiched graphic scenes of violence, starvation and harsh elements between conversational minutiae like the weather, requests for goods, Christian expressions of gratitude, and words of affection. Sometimes letters were six or seven pages long and delicately written, and other times the same soldier wrote hastily scribbled notes; the emotional and physical distress visibly apparent on the page. Sometimes soldiers abandoned syntax in their letters, they changed their usage of punctuation and defied grammatical rules to convey the depths of their anguish.

Additionally, while this analysis of trauma includes the physical violence of battle, it is not limited to such events. The letters sent by soldiers indicated that environmental dangers, disease, and isolation contributed to the complex nature of their psychological damage. Richardson also provides insight on approaching historical narratives with a trauma-informed praxis. “The point is that trauma qua cause is not the event itself, but something that is missing for which the event comes to function as a placeholder. Thus, a person may develop a symptom many years after an event has taken place.

History in such cases must be read as addressing the present, not the past.” [6] Connecticut soldiers rationalized their suffering with their written words, the events they recorded were placeholders for the relationships and memories that were ripped away from them as a result of war. Additionally, prior inquiry on trauma is typically centered on post-traumatic stress; the months or years following incident(s). This research specifically examines events during or shortly after soldiers experienced their trauma. Reorienting historical analysis to interpret events as they occurred, further exposes the profound and personal psychological ramifications of war.

While there is limited historiography on Connecticut Civil War trauma, one invaluable source includes Michael Sturges’ article, “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Civil War: Connecticut Casualties and a Look Into the Mind.” In his 2014 essay, Sturges argued the psychological trauma which resulted from the Civil War has always been with us as a nation as evidenced by Connecticut veterans’ lives in the years following the war. Examining 19th century perceptions of mental health and cases of post-traumatic stress, he illuminates the effects of the war on the human mind. Using census data, government records and now restricted patient records, Sturges’ findings exposed Connecticut’s Civil War veterans suffered from alcoholism, volatile behavior, domestic violence cases and institutionalization from 1868-1890.[7] This inquiry will build on Sturges’ prior work and reinforce his arguments; serving as a prequel, it will contextualize the soldiers’ trauma as they lived through it in real-time and their coping strategy of letter-writing.

Connecticut soldiers were not aware of the psychological benefits of writing, but now there is long-standing evidence that oral and written communication are effective methods of stress relief. In 1952, Alvina Treut Burrows highlighted the value of expressive writing as a therapeutic method. “Thus, it appears that stories, drama, verse are not only art forms. They offer opportunities for the projection of personal power to the sympathetic listener. The interaction of writer and audience is reciprocal, active, releasing.” Written expression serves an emotional need and has a stabilizing effect on the writer.[8]

More recently, researchers discovered writing helps develop the frontal lobe, which is involved with language production, voluntary movement and executive functioning.[9] For Connecticut soldiers, writing and receiving letters was a form of healing and catharsis, as indicated by 16th Infantry member, Cecil Barrett. He wrote to his wife, “Let me say again, that nothing does a soldier so much good as letters from friends. I am satisfied you do, all I can ask in that respect- only keep on so, and you will do more to help and encourage your husband in this toilsome, lonesome, fighting- away-from-home, soldier’s life,- than anything you can do besides.”[10]

There is a physical, biological response that our bodies experience when responding to danger. A perceived threat activates the sympathetic nervous system, a rush of adrenaline surges to our brain and we go into an elevated state. It focuses our attention on the threat and usually evokes intense emotions of alarm and rage. When a person feels threatened, their brains will engage in a fight, flight, or freeze response to dangerous stimuli. According to Judith Herman, “psychological trauma is an affliction of the powerless. At the moment of trauma, the victim is rendered helpless by overwhelming force. When the force is that of nature, we speak of disasters. When the force is that of other human beings, we speak of atrocities.” Long after the danger is averted, the body persists in an altered and amplified state. Traumatic events leave the person in a lasting state of hypervigilance and changes in emotion, memory and cognition.

Herman defines the three main categories of post-traumatic stress; hyperarousal, intrusion and constriction. In a state of hyperarousal, “the traumatized person startles easily, reacts irritably to small provocations, and sleeps poorly.” The survivor is in a constant expectation of danger. Long after the traumatic event, people will relive the event as if it is constantly reoccurring in the present. Intrusion is the imprint of the disturbance and “becomes encoded in an abnormal form of memory.” Constriction embodies the paralyzing response of capitulation. When a person feels powerless, their body can go into a complete state of surrender. The mind-body connection associated with self-defense shuts down entirely and the body will literally freeze. This is often expressed in the form of hypnotic states, psychological numbness and dissociation. Sometimes people who experience traumatic stress will oscillate between hyperarousal, constriction and intrusion to form a chaotic rhythm of helplessness[11].

Connecticut soldiers faced many violent threats as they traversed the South throughout the war. Losing comrades, mass death, and the tumult of battle constantly endangered their lives. Writing to their family back home was one of the few ways they could cope with feelings of hypervigilance, to process this mental and physical strain. James Elliot Ford, a member of the 15th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, wrote to his mother of his encounter at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 11, 1862. His infantry was called at four in the morning and were told to dress and get breakfast as soon as possible.

Chaos ensued as soldiers “flew around and got ready and had 3 days rations dealt out to us.” Firing commenced at six a.m., the rebels opened fire on their forces as they put down the pontoon bridge. Confederates got halfway across the river when they fired from there. “There was a steady fire kept up till 12 noon when it ceased…We fell in at 7:00 with our woolen + rubber blankets rolled and 60 rounds of cartridges we have to be in readiness to go to fight at any moment, send me 2 or 3 stamps.” Ford then resumed writing the next day, on Friday. He informed his mother firing had started up again and noted a large smoke coming from the direction of Fredericksburg and wondered if the city was on fire.

Unlike his writing from the day before, he did not bother to describe a play-by-play of events. He stated he knew the newspapers were likely going to give a better account of events than he could ever write. There was terror and exhaustion in his words and in his handwriting, as he could hear fighting resume from a distance. He scribbled, “I shall try to it with a brave heart and shall try to come out with a whole skin. If I fall, I hope that go to my last good home. Keep a brave heart mother until you hear from me again.” As he signed off the letter he told her, “Firing has begun again give my love to inquiring friends and tell them if you have a mind to that I have marched 100 miles with a heavy load, and had 3 drills now I feel like a lark.”[12]

At the beginning of Ford’s letter depicting the battle, he was clearly activated as he meticulously gave an hour-by-hour run-down of events. By the next day, his messages were shorter as he became more fearful for his life as he wrote down each moment he heard firing ensue in the distance. Writing gave him something to do as he likely felt powerless to the sounds of gunfire inching closer and closer to his position.

Corporal John Harpin Riggs of the 7th Regiment wrote to his parents throughout the war and recounted his assigned task at Fort Hilton, South Carolina. Riggs had to bury a mass grave for Confederate soldiers who were killed during a bombardment. During the assault, he recalled bullets flying past his head, going at least one-hundred miles an hour, by his estimation. Riggs did not know how many were killed in total, but he had to bury at least twenty soldiers. “The first dead man I saw had his head split with a piece of a shell his jaw was about 4 feet from his head he held a cannon swab in his hand he was a gunner I took the bread out of his haversack and eat some of it.”

Afterwards, Riggs buried a private that was shot in the back with a cannon ball, he set a plant at the foot of the grave to serve as a marker. He then abruptly changed the subject and wrote about the long hours on picket duty. While he found it tedious, he much preferred it to battling. By May of 1863, he counted himself part of eight battles but he never saw bullets come so fast as they had the day prior. Once they were ordered to retreat, he never saw such relief from his comrades. In September of that year, Riggs did not mince his words as he recounted the brutality he witnessed.

“I have seen some of the most horible wounds that man ever saw from shell but the most horable of all was in Fort Wagner when the rebels left they left their dead and wounded in the fort and I, being among the first to go in, saw them just as they were left there was four men piled up in one place which from all appearances had layed for two days in the sun and they wer very mutch swolen and full of magets and smelled sickning enough and there was a man who had been wounded 3 days without any aid from the doctors and he was all mortifyed and died as soon as we brought him out of the fort it was all baptized in blood and smelled very bad I wonder how they stayed as long as they did.”

Despite graphic depictions of bloodshed, Riggs never dwelled on these images too long in his letters. Either he did not want to disturb his parents, or he wanted to shift away from the subject, himself. Whatever his motivation, Riggs often unexpectedly changed the topic of violence to requests for goods or simply ended the letter. John Riggs’ letters also reveal deeper layers of the trauma of violence that reside at the heart of the Civil War: racialized violence. After the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, Riggs vocalized his racial animosity; making it clear he was defending the state, not the abolition of slavery. And he certainly did not want to fight alongside Black soldiers.

“I do not want to fight any longer when I enlisted I came to defend the flag and to keep the Union as it was but they have turned this war into a nigger war and I want to get out now as soon as posable… our military Govener had the black devils turned out an told them that they were all free men could do and act as they choused and that if they worked they could demand pay and all sutch things now you never not expect soldiers to like this mutch to have them black whelps lying around if they get in my way I shall poke the bayonet through them that is so. The thing is played out with me if ever one of them comes to get in on me I will send him back double quick.”

He knew his opinion of Black people was unpopular among his fellow Union troops and surmised if anyone knew what he thought they would tar and feather him. He quickly changed the subject to tell his mother he would send her a piece of cloth from the pants he wore so she could see the hole where he was wounded in battle. Before he ended the letter, he ruminated on the possibility that if anyone found out how he felt about emancipation, he might be taken as a prisoner and released on parole.[1] Based on his words, there is no denying Riggs was racist against Black people. Fighting a crusade he no longer believed in, left him feeling dejected and isolated from his fellow soldiers.

The rift between ideologies could prove to be dangerous on the war-front. In times of perilous danger, one wants to trust the people they’re fighting alongside. For Riggs, it was only in the letters to his parents that he felt a sense of intimate privacy to express the violent animus that lived in his heart. According to Judith Herman, soldiers are “invested in the small combat group. Clinging together under prolonged conditions of danger, the combat group develops a shared fantasy that their mutual loyalty and devotion can protect them from harm.”[2] Soldiers who felt detached and lost confidence in the Union cause after emancipation, were both dangerous and in danger. If allyship was essential for survival, anti-Black racism directly threatened the lives of both white and Black Federal soldiers.

With slavery, racial hierarchy, and emancipation at the heart of the conflict, race was deeply rooted in Civil War trauma. Letters written by Connecticut’s Black soldiers provide evidence of their unique experience. Joseph Cross’ letters to his wife, Abby Jane, provide crucial examples. Cross was part of the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment and in October of 1864 near Richmond, he depicted how they nearly died fighting Confederates.

Union troops were overcome with exhaustion but on a dark and foggy morning, they fought rebel forces and managed to push them back four miles. The 8th and 9th Pennsylvania Regiments lost over three-hundred men as the 29th CT Regiment marched forward and onward. Bullets flew past their heads as they thought this was going to be their last day on earth, but eventually, the Confederates retreated. He depicted the aftermath of the battle to his wife, “some was shot in the face + eyes some in the arme + legs feat hands + some lay dead in the field + some Crawling on their hand + knees trying to get away.”

He quickly changed the topic and described the flora and fauna of the South and sent some cotton seeds along with the letter so she could see the plant for herself. In March 1865, Cross depicted an incident where one of his fellow soldiers disguised herself as a man to fight, but her identity was revealed when she had a baby. “Did you Ever hear of A Man having a child their is such a case in our regement + in Companey F She played man Ever since wee hav been ot the child was Born feb 28…”[15]

Little else is mentioned about the female soldier and her fate, but Cross’ account reveals the resilience and bravery of Connecticut’s 29th Regiment, despite the odds stacked against them. The conditions for Black soldiers were more dangerous than their white counterparts, in more ways than one. Disease and mortality were much higher; in the 29th Regiment, 152 enlisted men died from disease, versus forty-four who died in battle.[16] Despite that, they valiantly fought the most important battles in the final year of the war.

Cecil Barrett’s experience further illuminates the complexity of human suffering throughout the Civil War. Barrett was a member of the 16th Regiment and endured the battles at Antietam, Maryland, where he was wounded and captured. He was also present at Fredericksburg, Suffolk, Virginia, and for Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. In February of 1863, only six months into his service he wrote, “A man in the 15th CT (near us, in the same row of barracks) cut his throat from ear to ear so that he died very quick, -with the razor of one of his company; the other morning, when all but himself were out to ‘roll-call.’ Reason supposed to be, insanity. Don’t recollect his name or residence.”

It is likely the soldier Barrett described, suffered from the aftermath of traumatic events which led to his suicide. As combat veteran Tim O’Brien describes, war for the common soldier carries a spiritual texture “of a great ghostly fog, thick and permanent.” What is true and untrue blur together along with order and chaos, love and hate, law and anarchy. The survivor feels disoriented and overwhelmed by ambiguity. “In war, you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself.”[17] Survivors of traumatic events are often left with shame and guilt as they are forced to face the reality of their helplessness.

Throughout the war Barrett depicted his run-ins with human suffering. In a March 1863 letter to his wife, he described a day in which he met a group of formerly enslaved people and saved a Black infant from drowning in a large puddle. The child’s misfortune occupied Barrett’s mind. A deeply religious man, his faith in God assisted him in coping with these disturbing events. In April that year, at the Siege of Suffolk, Barrett wrote to his wife on a Sunday, which was not normal for him as he usually refrained from work on the Sabbath. However, he needed to inform her of “some excitement.” There were skirmishes and rumors that rebels were gathering a large force a few miles away from them. The men on picket duty were shot and wounded and the demonstrations were just the introduction to a longer attack. “And to add to the excitement and determination on our part- one of 8th CT, who was out on the picket- came in wounded…”

By Barrett’s estimation, Confederates were getting desperate because they were starving and felt they needed to do something soon or risk total collapse. He confirmed that it was true, the rebels were short for food and that three-hundred women in Richmond rioted and broke open the Government Store House for bread. “It certainly does look as if the rebellion now was “on its last legs.” God grant that it may be so, and that we may soon have a righteous peace.” He informed his wife that as long as they were threatened by the “rebs,” he would write to her at least twice a week to keep her updated. He then instructed her to “Keep this letter- it may be of service as a history of this affair…”

In February of 1865, Barrett was near Chaffin’s Farm in Virginia and wrote to his wife about his hopes that Confederate forces were weakened, despite the firefighting he witnessed. “There was yesterday, a very rapid and heavy cannonading on the other side of the James; – some thought it was as far as Petersburg, and there are rumors of a battle on that part of the line…” He saw rebel troops running over to the Union side, surrendering their weapons and deserting the cause in exchange for food rations. “…the ‘Southern Confederacy’ is gone up.” They may fight some hard fighting yet,- but it will be the fighting of desperation- not of hope, and we believe will be short.” On April 9, 1865, the same day as the battle of Appomattox Court House, Cecil Barrett was promoted to 1st Lieutenant for the 31st (Connecticut) United States Colored Infantry. The very next day, he penned a letter to his wife to tell her the news of Lee’s surrender and the events that transpired.

He called the battle the “final consummation,” as General Lee’s rebel army “laid down their arms and were surrendered by Gen. Lee himself to Lt. Gen. Grant. Let us praise the Lord and render unto Him the thanksgiving of grateful hearts!” Barrett thought the Confederate privates were just as relieved as he was that the fight was over but speculated whether some would engage in guerilla warfare but he hoped this was not the case, as in his view, it would harm Southern civilians more than Union troops. In his letter, he described the battle in great detail; the movement of soldiers and the strategy of Grant’s army which forced rebels to swim a large portion of the river as the Union fighters surrounded them.

He marched thirty-two miles in one day and when they finally met up with the rebels, they saw a sorry vision of an army. “His army weary, ragged + hungry. After about two hours of hot very heavy fighting… the “white flag” was raised- and “the day was ours.” Prisoners of war were then returned from each side. Confederates who were imprisoned by Federal troops were returned with 25,000 food rations. Union soldiers captured by Confederates were not given the same consideration. “They captured some 6 or 700 from us at different points since we left and kept them with them, and they did not receive anything to eat for three days except now and then an ear of corn.”

A month after the battle at Appomattox, Barrett was promoted to Captain, his courage and bravery was recognized. Despite that, Cecil Barrett never romanticized his experience of the war. All around him, he witnessed agony and suffering and now that the war was over, his relief reverberated on the paper. “And o how “sweet” indeed, will my dear home then be to me: “Sweet, sweet home,” with my country’s enemies all defeated, conquered- all peace and quiet!”[18] Soldiers like Barrett relied on their communities back home for restitution and restore a sense of meaning in the world. Their families and broader network were essential to rebuilding order and justice in the mind.[19]

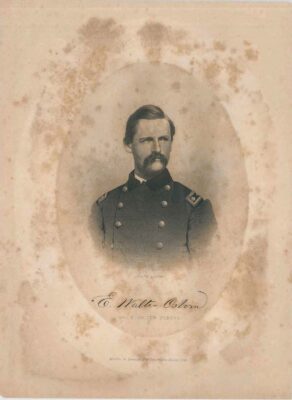

Connecticut soldiers encountered violence throughout the entirety of the Civil War. The constant risk of running into the enemy, battles and skirmishes, mass death and even the violent thoughts in their own minds, were daily struggles for them. Death was everywhere, enough to trigger feelings of depression and terror. One of the few coping mechanisms available, they turned to the act of writing it down and informed their support networks of their struggles. Connecticut soldiers through every rank and file grappled with their reality. Major Eli Osborn wrote to his brother and captured the tension between remembering and the desire to forget that traumatization ignited.

“Still, it must be expected of a soldier; death is always near him. And yet not particularly the soldier; it is as near the citizen as he who faces the cannon’s mouth. I do not moralize very often, for I do not like to think of these things much, they are so apt to give me the blues.”[20] A 2005 Stanford University psychological study demonstrated that those with depression typically respond to negative life events with pessimism and rumination. Intentionally forgetting a memory becomes a powerful, maladaptive coping strategy for the victim. “With guided and repeated attempts to forget negative material, depressed persons could reduce elaborative processing and, consequently, negative recall.”[21] Recording a disturbing event in a letter and then deliberately forgetting about the memory possibly developed into an emotional management schema for soldiers.

For almost the entirety of the war, soldiers labored outside in extremely difficult environmental conditions with almost no protection from the elements. There was a common belief that nature was a “significant and sometimes definitive force in shaping their physical and mental health.” While germ theory was in its infancy stages during the Civil War, nineteenth century perceptions of physical health displayed an intricate awareness of the mutuality of the mind, body and environment. Soldiers who experienced frequent physical illness often felt bouts of depression and melancholy. If they fell ill back home, they relied on women in their families to nurse them back to health.

During the war, they were forced to rely on doctors and surgeons who had little understanding of disease. Camping provided adequate shelters for soldiers, but there were disadvantages to living among thousands of other men. Contaminated water, lice, and heat stroke are just a few examples of what contributed to a culture of low morale. According to Kathryn Meier, twenty-two percent of men frequently complained of low morale, and an additional twelve percent recorded “periodic plunges in their spirits.”[22] For many soldiers, the natural environment was a source of psychological disturbance.

Far from home, Connecticut soldiers struggled to adapt as they fought Confederates in battles and skirmishes in their home territory. New Haven native, Sargent William Eldridge Bishop wrote to his cousin Nellie in March of 1862 and described his experience in the battle at Fort Donelson in Tennessee. “…we fired the first shot at 11’/a the rebel Boat had now pressed by the obstructions that been placed by them from Fort Barlow to the main land our boat with several others opened fire on them and the remainder of the fleet attacked the forts for upwards of 7 hours the shot and shell fell around us and at a terrible rate but as luck would have it, none hit our Band although they struck within 6 feet of us.”

Once fighting ceased on the ship, Bishop described transporting the challenges of the environment as they transported artillery. For nearly the entire night they cleared the weapons through a swamp, water and mud went up to their waists as they walked to the rendezvous point. Exhausted and impossible to dry off, Bishop did what he could to resist hypothermia. “And I shudder now to think how I suffered during that Long, Long night, wet through and through and so tired from the fighting of the preceding day as to be severely able to sleep but we could not lay down. I was so Cold that I eventually took off my shoes and rubbed my feet to keep them warm…”[23] Wet, freezing conditions coupled with the exhaustion and excitement from battle, were sources of Bishop’s agony.

James Elliot Ford wrote to his mother about his challenges with the natural environment as he dealt with chronic illness and hand tremors. In November of 1862, he wrote, “For the past week it has been foggy and rainy every day until yesterday where it cleared off and the wind commenced to blow and at 7 o’clock it blowed a perfect hurricane and I thought it would blow the tent over. These Virginia winds are not like old Connett [sic] winds…” Ford hated picket duty, especially when it was raining. After the rain, the mud was ankle-deep and made completing duties particularly tedious.

In June of 1863, he was stationed near the White House where the rain went on nearly two weeks. “Oh what weather! Rain! Rain!! Rain!!! When will it stop. We left Portsmouth 11 days ago and it has rained every day since.”[24] Indeed, precipitation added stress to troops stationed throughout the South. Rain was the most frequently recorded threat to health, according to Kathryn Meier. “Precipitation was the most commonly cited cause of disease in 1862, and official Union medical records confirm the spike in wet, cold weather in the Shenandoah Valley corresponded to increased rates of sickness.”[25] Rain was more than a nuisance when one spent most of their time outdoors, it dampened their spirits as much as their clothing and made them susceptible to disease and psychological stress.

Corporal John Riggs also faced challenges with his natural environment as he recounted his return to South Carolina. “You will see by the heading that we have got back to the old place of misery and starvation and flea bites there is only five companies of us to do the guard which took a whole regiment 1,500 strong to do before we came here…” In November 1863, his regiment went ten days without bathing or changing their clothes. The lack of hygiene was just as much of a threat to his life as a rebel attack. “I shall be lucky and you shall hear is I come out alive and if I am killed, killed I am in the right and not in the wrong to be sure.”[26]

Connecticut soldiers documented their experience with spatial trauma. Traveling through foreign lands, exposed to the elements, soldiers were threatened with the adverse effects of the southern climate. According to soldiers’ accounts, the weather, climate and the local terrain contributed to their demoralization.[27] The words used to describe their surroundings expressed as much stress and grief as their depictions of fighting Confederates. In their minds, where there was bad weather, there was sickness and possible death.

James Ford often documented his sickness and while it is unknown what his diagnosis was, through his letters, it is clear from his frequency of documentation he was dealing with a chronic illness. In September of 1862, he wrote, “I am, have been sick for a week but are getting better now. I am pretty weak…” Days later, he was worried they weren’t getting any of his letters, as he scribbled about the rain and how everyone around him caught colds. Two months later, he was stationed at Camp Casey and reported his difficulty in penning letters. “I have not had any shakes in a week but I do not know how long it will be before that I shall have them again, I hope not never, I hope that I have my health hereafter and help to fill up the company. There are a great many sick.”

In addition to reporting his bouts of sickness, Ford also frequently wrote about the meals he ate. The letters contained vivid explanations, especially when it was a full meal. It is possible as he adjusted to the reality of periods of starvation, he felt compelled to record the moments he experienced nourishment; the times in which he ate a proper meal was memorable enough to write about. He might have also wanted to assure a worrying mother that he was, in fact, eating. Prior to the Battle at Fredericksburg, Ford was not feeling well, but they had marching orders to travel fifty miles south. By March of 1863, he needed to write in pencil because his hand tremors made it too difficult to write in pen.[28]

Soldiers often wrote to their families after they recovered from an illness. It’s possible they were too sick to muster the energy to pen a letter. It’s also feasible in some cases, they did not want their family members to worry. If they wrote to them after they were in a state of recovery, it would ease their anxiety. Feeling trapped within a hospital, letters served as a sort of medicine. Though, it is true that grimly ill soldiers did not have the fortitude to write home and receive the reciprocal benefits.[29] Both Cecil Barrett and John Riggs wrote to their families after they’d recovered. In Newport News in February 1863, Barrett assured his wife not to fret, “I am in good health except a little cold. I have had a very bad cold, accompanied with a hard cough, & a stuffed & sore throat. I never had a worse cold. Got it last week in the rain. But it is about well now,- so need not worry any, feel very well now.”[30]

For John Riggs, his illness resulted in hospitalization and was the first time he’d ever been in a hospital. While he was recovering, financial insecurity was adding to his stress. The army hadn’t paid him and asked his parents to send him greenbacks. If he was allowed to leave the hospital and return to his regiment, he would be able to inquire on the payment, but they wouldn’t let him. “I shall go, go to my regiment as soon as possible for I can get better care in my company if they would let me go but they will not yet. Never mind we shall all be around again if we live. I had a fever but it has left me now but I am awful weak…do not worry about me now, I am most well now.”

Riggs’ experience in the hospital left an imprint on his mind. In future letters, he often wrote about other soldiers getting sick, reported how he was physically feeling, and vocalized his anxieties about falling ill again. Near Wilmington in June 1865, he told his parents, “I am feeling first rate now and think I shall stand this climate good but they say it is a great place for yellow fever here perhaps we may miss it… I hope so for it is an awful disease, it is worse than the smallpox.”[31] Aware that he occupied a foreign territory ripe with epidemics left him horror-stricken.

Eli Osborn too, felt terrified of developing illness and often wrote to his sister about his concerns with contracted disease. In his February 1864 letter, there was a malaria outbreak at camp. “We are all well so far out here in this barbarous country, but I expect every day when we shall have men down with the ague. I have been free from any disease yet, but do not hope to escape this. Almost every man who has been on duty here has had it sooner or later. I do not fear it, but it is decidedly unpleasant.” While he claimed he did not fear falling ill in this instance, a year later his perspective changed as he stated disease was more fearsome than fighting. “I may be peculiar in this respect, but I had rather run risk of stopping a bullet than of the yellow fever.”

Unfortunately, it was not disease that made Major Eli Osborn a casualty of war; at the age of thirty-one, he was killed at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6th, 1865. For Connecticut soldiers, bullets and germs were equally fearsome and just as deadly as the other. They were surrounded by hardship, filth, disease, and dying. Their families unable to nurse them back to health brought a loss of security and reinforced the fear of environment during the war. In this way the traumatic events they endured became placeholders for the love and care they missed.

Homesickness may not seem like a traumatic event on the surface, but for many Connecticut soldiers, the Civil War was the first time they were so far away from home. Soldiers experienced loneliness and periods of depression as they witnessed horrors, displaced from their social networks. Throughout their letters, they expressed a yearning to be with their families. Especially when family members back home fell ill, soldiers felt helpless as they were hundreds of miles away, unable to help. Before they departed for the South, Barrett was distracted by his daughter’s illness and hashed out the logistics of coming home temporarily.

He was stationed at Camp Williams in Hartford in 1862, and as he brainstormed the possibilities, he knew it was not probable. “I would not care so much about going home if Sissy was well… if I only knew you were all well, I could be contented, but I can’t help worrying about Sissy.” Further in the letter, as he anticipated the long road ahead of them, Barrett asked his wife to send him doughnuts to remind him of the comforts of home. “I don’t expect to have any other opportunity for a long long time to get any such luxuries.” A religious man, he was relieved that other Christian soldiers in his regiment agreed to host prayer and worship in their tent. “They have all consented too, in our tent to have “family worship” every day aint you glad of that, it will seem most like home of anything… Remember the dough nuts.”

For some soldiers, religious faith was an anchor to a sense of community among the ranks and solidified their connection to their lines of kinship. Months later as he was marching near Harper’s Ferry, he asked his wife to write to him at least once a week, “You can’t think what a comfort and solace it will be.” He spoke often about God, and how blessed he was to have a family, speaking about his children often. He would also write messages periodically to his children, instructing his wife to read it aloud to them. For example, to his son Horace he wrote, ““Imagine I am at home, every night almost, no need of telling me. Well Horace, you sly cunning “papa’s baby,” if I could only get hold of you, I’d hug you + kiss you. You may have this letter when mama has done reading it, and sleep on it if you want too.” Like other soldiers, Barrett often wrote to his wife unprompted and when he had free time, he took the pen to paper to record a few words.

In September of 1863, he was anxious when she wouldn’t write regularly and requested a routine so he would know when to anticipate her letters. “I would rather you mail me a letter every Monday if you can, and I will try to give you one every Saturday night, it will be much pleasanter to be regular and know when to expect letters both sides.” He didn’t want to burden her with his problems so he hesitated to describe his woes but wanted to hear all about her struggles, hoping he could provide some support, despite the distance. “…God will take care of me: But you may tell me all about your trials,-yes tell me all and I will help you all I can, dear wife.” Catherine clearly did not keep up with the letter-writing routine because a week later, Barrett begged her to keep with the schedule. “When I do not get a letter the regular day for it, I cannot help feeling some anxiety for fear you may be sick; or something the matter of you or the children.” He expressed his homesickness, sending his love to his wife and children.

While Cecil Barrett struggled throughout the war with heartsickness, he recounted a moment he witnessed of family reunification that impacted him. He met a Black soldier in the 31st Regt. who was sold five years ago from his family in Kentucky, to work at a cotton plantation in Mississippi. He never thought he was going to see his family again, “till a day or two ago he met his own brother in another Regt. of this divn [sic]- who had enlisted from KY.” The man told Barrett, “wasn’t we right happy to see each other.”[32]

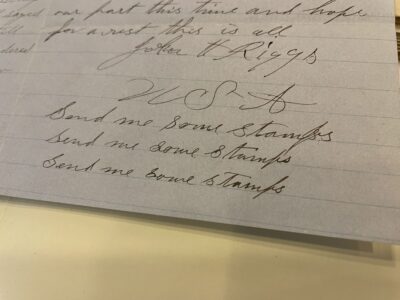

John Riggs also wrote to his family often, unprompted. In many of his letters he mentioned that while he hadn’t heard from them in some time, he wanted to update them on his whereabouts. More than any other soldier examined, Riggs was constantly asking his parents to send him goods, clothing and money. He signed off one letter, “Send me stamps. Send me stamps. Send me stamps.” In a following letter to his sister, he thanked her for sending him postage, otherwise he wouldn’t be able to write to them. Riggs’ letters indicated immense boredom with service at times and a longing to be home. “It is very warm day and I do not know what to do so I will write a short letter to let you know where I am…” As the war progressed, however, his letters took on a more vengeful air. When he learned about his uncle’s death he wrote,

…”tell them I have an uncle to avenge yet and if the war last 10 or 15 years I shall be a soldier in the union and for the flag and if I ever I get home and one of my friends speak against the union I will shoot him as quick as any dog he is no better. Good bye for this time give my best respects to all tell them my name is union jack

For ever

J.H. Riggs”

As the war progressed, Riggs expressed a desire to be home as he became demoralized. “I never was so homesick as I was when I got back first that was last Sunday…” Riggs was out of his element in the South, fighting alongside his fellow Union troops. He could not confide to them about his anti-emancipation sentiments nor did he enjoy the culture of North Carolina. As he was stationed in Wilmington in 1865, he documented his disgust with sex workers residing in-town. “I think besides many other things that are most prominent there is the most prostitutes and bad women I ever saw in any place the most filthy and slovenly the world ever saw.” Riggs felt culturally displaced and unlike Barrett, did not manage to establish a sense of community within the regiment and it is evident from his letters that over time, it wore him down.

Eli Osborn often wrote to his sister about his relationship with depression and indicated that letter-writing helped alleviate his stress. He often asked her about women they knew back home, as a single man in his early 30s, he was hoping to court one of them if he survived. He asked his sister to write him as much as she pleased, her letters were a great source of joy for him. In October 1863, he said he had “the blues,” which was a common way people expressed feeling emotions associated with depression.

The regiment was away and he was lonely at camp, “To be sure I have my guard with me, but they are no companions, and even if there be intelligent men among them it would not do for me to associate too freely with them. Therefore, I am quite desolate, and feel like asking to be relieved and sent to my regiment.” He lamented that he had to decline a wedding invitation he received, upset that he had to miss events back home. “I received the aforementioned wedding cards, and should rather like to attend, but I hardly think I shall.” A year later in November 1864, he was stationed at Roanoke Island and once again, experienced a bought of depression. He was tired of being surrounded by all the sickness and disease. He wrote to his sister in hopes it would serve “to drive away the blues.”[33]

Near Chaffin’s Farm, Joseph Cross did not know when he was going to be paid next, but as soon as he was, he promised his wife Abby, he would send it to her at once. He feared she was skipping meals and he wanted her to promise him she would try to eat as much as she could. Two months later, he rejoiced after receiving a photo from home. “My Dear wife I received your kind + welcom letter + I was happy to receive it + the Picture you Cant imagin how it made me feal + to think that I have been away from home + have been deprived of your happiness but still the Good Lord has spaired me to Behold your likeness on A Card.” Only two weeks later, however, he felt helpless as Abby was dealing with sickness back home. Cross tried to apply for a furlough to return home and care for her.

“now Abby I am trying to get a furloh to come home I sent a letter to alexander H Lester to have him right to the colonel that my family is sick + kneed me at home + have the Doctor sign it + note I want you to try and see what you Can do for me please to ask the Doctor if he wont speak a good word for me + if you tell them that you are in sufering Condition I think the doctor will do it if I was at home I could manage Buisness…”

Despite his attempts, Cross was unsuccessful in getting furloughed, and simply had to hope Abby would be well enough to endure without him. In another letter, Cross spoke of his brother Horace, who was sick himself, felt anxiety that he could not be home with his ailing wife. “Horace was very much Grieved at his wife picture for she Looked so poor in the face + for all of that he kissed the picture.” [34] Leaving their families unprotected was a source of alarm and powerlessness for soldiers.

While Lyman Bradley did not have documented letters in the archive, his diary reveals his run-in with violence and long periods of isolation. On February 20, 1864, he was wounded at the Battle of Olustee in Florida. He was shot in the right thigh and was transferred to a hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina, three days later. He remained at the hospital for three months and every single day he wrote, “In the hospital.” Sometimes he commented on the weather, other times he simply said, “In the same place.” Bradley was not a man of many words, but it is in the absence of his words that indicates his deep isolation. For three months of his life, time stood still. He was discharged from the hospital on May 11th and returned to his regiment. Only three days later, on May 14th, Bradley was hurled into battle once again and fighting sustained until May 16th. “The Right came to camp all played out the loss of the Right in all one hundred and eighty-seven in killed wounded and missing.”[35]

After Lyman Bradley returned home from the war, his child, Hattie, practiced her handwriting and doodled throughout the pages of the diary. In this way, one observes the networks of kinship on the pages. The function of the object served as both a diary and then later, as scrap paper for his child. In the late winter and spring of 1864, the diary of Lyman Bradley served to document intense barbarity and extreme seclusion. Once he was reunited with his family, the pages served a more innocent pursuit. This isn’t to say that once the war ended, soldiers returned to their normal lives. For many, the trauma they endured from the Civil War had lasting, negative effects.

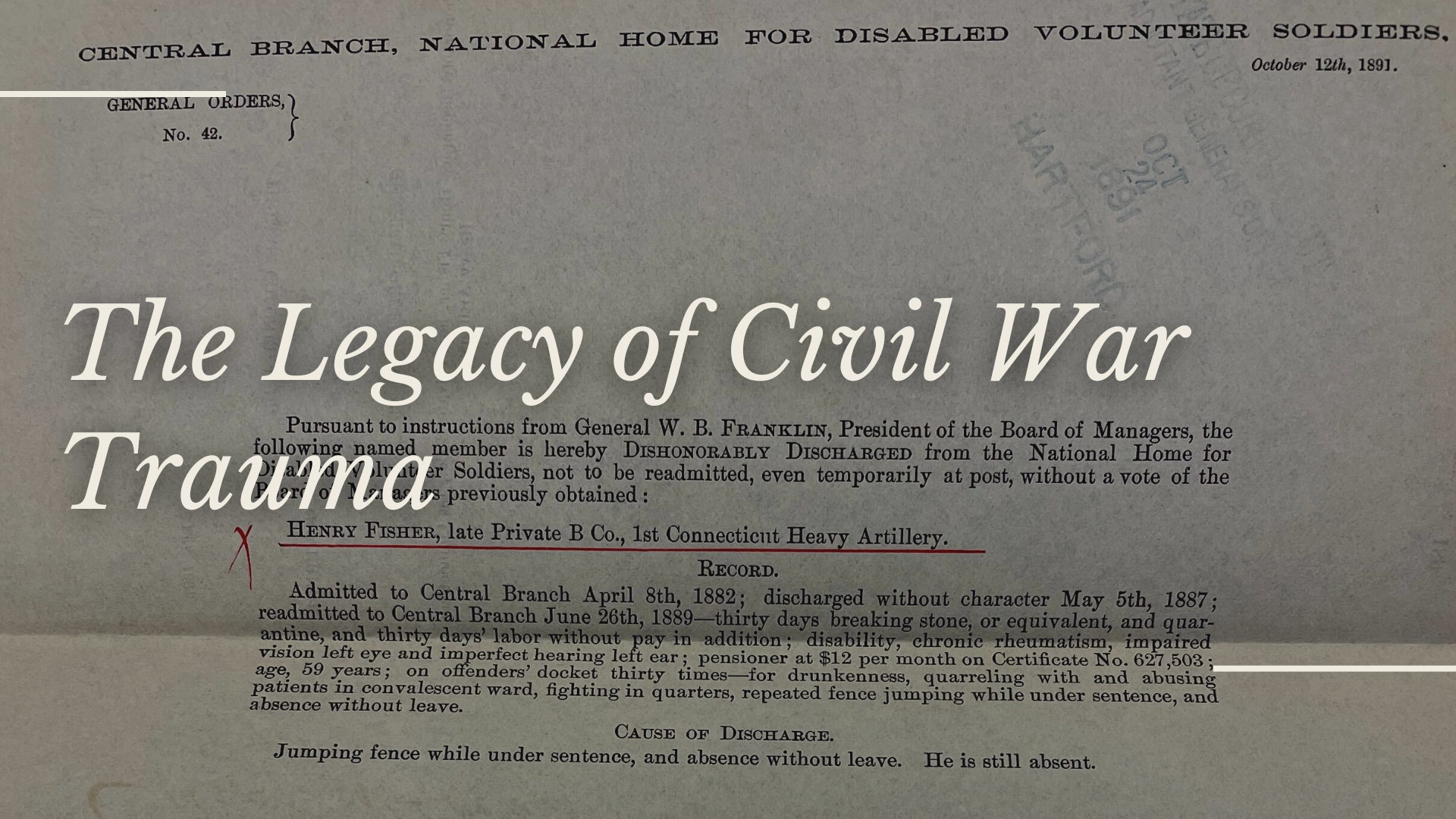

In the years following the war, many Civil War veterans struggled to return to civilian life. While the state invested in developing mental health infrastructure like the Connecticut General Hospital for the Insane in 1868, there was little understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder, as mentioned. The first veteran’s hospital in Connecticut was also constructed in Darien, Fitch’s Home for Soldiers and Orphans. However, it was through that institution that many found themselves dishonorably discharged for symptoms we now know are related to PTSD, such as alcoholism and erratic behavior.[36]

The 1880 Census survey entitled “Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes,” indicated veterans like Orlando Platt from Newtown, experienced houselessness along with his five children. His “heart affection” made him unable to work as Platt waited to receive his pension and back-pay from the U.S. government.[37] Men like Colonel John H. Burman, ex-postmaster of Hartford and colonel of the 16th Connecticut Volunteers, passed away at forty-seven at the state hospital for the insane. The years of stress and anxiety wore on him and by 1880, it was apparent to his family and friends that he was in mental decline.[38]

There are countless examples of Civil War veterans in Connecticut that struggled physically, mentally and financially in the decades following. They were not the only ones, this suffering reverberated throughout the state. The wives, children, friends, and extended family of fallen soldiers felt the debilitating effects of grief and loss. Premature death, involuntary hospitalization, and domestic violence afflicted veterans and their family members. Connecticut veterans’ trauma reshaped the foundation of community and familial bonds in the state and had multigenerational outcomes.

While this research does not focus on the decades following the war, the mounted evidence of PTSD in Civil War veterans only further supports the debilitating effects of war on both direct survivors and future descendants. The exploration of soldiers’ letters and recorded ephemera reveals the ways in which soldiers processed their trauma in real-time and the language they used to communicate that pain to their family and friends. We recognize their networks of kinship and gain a greater understanding for the ties that bound people to one another, either by blood or marriage.

Historians also get a glimpse into Connecticut soldiers’ relationship with the war, their opinions on preserving the union, slavery, and their relationship with Black Americans. The letters uncover violence, brutality and a fear of both bullets and infection. Food and economic scarcity lowered morale among the ranks and the southern climate adding another layer of oppressive exhaustion. Extreme loneliness prompted soldiers to send letters to pass the time and distract from the conditions of camp. Their correspondences with loved ones illuminated their open emotional wounds and their attempts to suture the traumatic effects of the Civil War.

Reference Footnotes:

[1] Guelzo, Allen C., Fateful Lightning: A New History of Civil War and Reconstruction, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 232-278.

[2] Herman, Judith, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 9.

[3] Meier, Kathryn Shively, Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2013), 120.

[4] Latiri, Ines, “I don’t know about you, but it all goes through my skin”: War Trauma Writing by Lawrence Joseph,” American Studies Journal, no. 64 (2018).

[5] Richardson, Timothy, “Writing (and Doing) Trauma Study,” JAC, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2004): 491-507.

[6] Richardson, Timothy, pg. 493.

[7] Sturges, Michael, “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Civil War: Connecticut Casualties and a Look Into the Mind,” in Inside Connecticut and the Civil War: Essays on One State’s Struggles, ed. Matthew Warshauer, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2014), 159-180.

[8] Burrows, Alvina Treut, “Writing as Therapy,” Elementary English, Vol. 29, No. 3 (1952): 138.

[9] Andres, Zoe. “Psychologically Speaking: Your Brain on Writing.” Writing and Communication Centre. University of Waterloo, August 4, 2022. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/blog/psychologically-speaking-your-brainwriting#:~:text=in%20the%20writing%20process%20once,hall%20into%20a%20written%20description. (accessed November 2, 2022).

[10] Letters from Cecil Barrett to Catherine, Barrett Family Papers, Ms. 98718, (Box 1, Folder 5), Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.

[11] Herman, pg. 31-47.

[12] James Elliott Ford letters, Civil War Collection, MSS. 77, (Box 8, Folder A), Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[13] John Harpin Riggs letters, Civil War Collection, MSS. 77, (Box 3, Folder E), Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[14] Herman, pg. 62.

[15] Letters of Joseph O. Cross, 1864-1865, Digital Manuscript Collection, Connecticut Historical Society, https://digitalcatalog.chs.org/islandora/object/40002%3ACross. (accessed November 1, 2022).

[16] National Park Service, 29th Regiment Connecticut Infantry (Colored), February 26, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/rich/learn/historyculture/29th-conn.htm. (accessed November 3, 2022).

[17] Herman, pg. 53.

[18] Letters from Cecil Barrett to Catherine, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut

[19] Herman, pg. 70.

[20] Major Eli Walter Osborn folder, Civil War Collection, MSS. 77, (Box 2, Folder A), Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[21] Joormann, Jutta, and Paula T. Hertel, “Remembering the Good, Forgetting the Bad: Intentional Forgetting of Emotional Material in Depression,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Vol. 114, No. 4, (2005): 640-648.

[22] Meier, pg. 1-13.

[23] William Eldridge Bishop letters, Civil War Collection, MSS. 77, (Box 1, Folder E), Whitney Library, New

Haven Museum.

[24] James Elliot Ford letters, Civil War Collection, MSS. 77, (Box 8, Folder A), Whitney Library, New

Haven Museum.

[25] Meier, pg. 46-47.

[26] John Riggs letters, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[27] Meier, pg. 49-50.

[28] James Elliott Ford letters, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[29] Meier, Kathryn Shively, pg. 120-121.

[30] Letters from Cecil Barrett to Catherine, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.

[31] John Harpin Riggs letters, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[32] Letters from Cecil Barrett to Catherine, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.

[33] Major Eli Walter Osborn folder, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[34] Letters of Joseph O. Cross, 1864-1865, Digital Manuscript Collection, Connecticut Historical Society.

[35] Lyman Bradley folder, Civil War Collection, (Box 1, Folder H), MSS. 77, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

[36] Fitch’s Soldiers Home and Veterans Home and Hospital Discharge Files, State Archives, RG73, Box 174, Connecticut State Library.

[37] State of Connecticut, “Census: Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes,” (Hartford, 1880), Connecticut State Library.

[38] “Obituary: Death of Colonel John H. Burman,” Hartford Daily Courant, April 11, 1883, https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/historical-newspapers/obituary/docview/554179781/se-2. (accessed October 25, 2022).