“Great things must be silenced or talked about with grandeur, that is, with cynicism and innocence…I would claim as property and product of man all the beauty, nobility, which we have given to real or imaginary things…”– Frederic Nietzsche

Between 1935 and 1938, thousands of Connecticut residents were surveyed by a state task force commissioned by Governor Wilbur L. Cross, who appointed a board of researchers to identify individuals they deemed unfit for society. The four-part survey was released on October 1, 1938, directed and spearheaded by Harry H. Laughlin, a notorious eugenicist who worked with the Eugenics Office at Carnegie Institution of Washington of Cold Spring Harbor, New York. The Survey of the Human Resources of Connecticut examined 169 towns and asserted tens of thousands of people were categorized as unworthy for residence in the state or for procreation. Further, the survey closely examined preexisting Connecticut state laws to make recommendations for sterilizations, deportations, state-barred marriages, and in some cases, euthanization.[1] Their definitions of “socially inadequate” individuals included people with developmental disabilities, addictions and mental illness, experience blindness, deafness, people who commit crimes, and people in poverty “due primarily to constitutional lack of initiative, or of physical or mental energy.”[2]

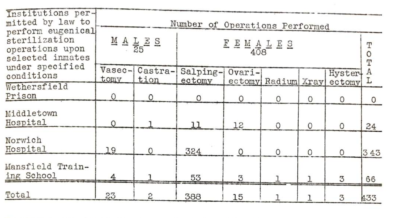

Simultaneously, the 1909 sterilization law was already in full effect; over four-hundred sterilizations were administered to individuals confined at the state mental hospitals and prisons by 1938.[3] Connecticut state legislators discussed euthanizing individuals with serious disabilities as far back as 1921.[4] Redlining and restrictive covenants in Connecticut barred individuals of specific races and religious descents from living in certain neighborhoods.[5] Deportations in the United States were also at an all-time high in the 1930s; over one million people of Mexican descent were deported, sixty percent of which were U.S. citizens.[6] While The Survey of Human Resources was never published and was swept under the rug of historical memory after Governor Cross lost his reelection in 1938, eugenics influenced many policy measures enacted in the state in the decades following.

Governor Cross was known as a New Deal Democrat who helped lift the state out of the Great Depression. There are buildings, a highway, and prestigious awards at Yale named after him in the state, and yet, he was an instrumental figure in one of the most insidious studies ever conducted on Connecticut residents. Why would Governor Cross commission a eugenics survey and how does this survey and Governor Cross’s life illustrate the ways eugenics was part of the domination of ideological and physical space, reflecting a larger white settler colonial project? This research will examine the Survey of Human Resources in depth, as well as the life of Governor Wilbur Cross as he describes it himself in his autobiography, to identify spatial dimensions of the eugenics movement and the generational process of the production of space in Connecticut.

This critical investigation will argue the protocols of the survey, its findings and its recommendations, illustrate early twentieth-century methods of surveillance and control of people occupying intellectual and environmental space. The autobiography of Cross is a crucial primary source where he connects himself to the ideas purported in the survey, and how he was intertwined with the eugenics movement. This source illustrates that despite his New Deal accomplishments, his legacy should be remembered as being a descendant of settler colonialism and the genocidal premise of dominating space, resources and people.

The survey was divided into four parts and each one provided significant assertions with little mentioned on methodology. Part one, “Family-Stock Betterment in Connecticut,” details why this survey was conducted in the first place and a summary of their recommendations and findings. Part two contains case studies of eight families residing in the state and asserts their findings are proof of genetic feeblemindedness and the necessity for state-enacted birth-control measures to prevent future disabilities and “degenerate racial stock.” Part three, an analysis of the laws in Connecticut and how they can be applied and expanded to enacting eugenics policies on the general populace. Finally, part four is a portfolio of fifteen charts concerning race betterment and feeblemindedness. This research will examine the first two parts of the survey as they provide crucial assertions about human society in Connecticut and eugenical proposals to spatially transform the region, permanently.

Henri Lefebvre’s spatial critical inquiry informs the topic of eugenics because it provides a framework for examining these connections between the philosophical and the actionable, between the abstract and the physical. He asserts that urban space is shaped and fashioned by the social activities and that organized space assigns the relations for reproduction. Space is a process shaped by contending forces like class, grassroots movements, experts, and policy. Eugenicists believed this process was biological and natural, but Lefebvre argues space is produced and reproduced through human interaction and intention.

The ideas deployed in state institutions shaped Connecticut socially and politically, which targeted immigrants, people of color, people with disabilities and non-normative identities. Integrating Lefebvrian spatial theory in analyzing these primary sources, this research will identify Connecticut’s deep roots with the eugenics movement, and how one of its most venerated figures in state political history was instrumental in providing the blueprint for challenging human agency, autonomy, and the right to self-determination.

Harry Hamilton Laughlin

Harry H. Laughlin was one of the leaders of the eugenics movement in the United States throughout the early-mid 20th century. He was the superintendent and assistant director of the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, NY, along with Charles Davenport. In 1922, Laughlin published the book Eugenical Sterilization in the United States, which influenced policy and practice throughout the nation pertaining to reproductive control and compulsory sterilization. Harry Laughlin was born in Oskaloosa, Iowa on March 11, 1880, and was the eighth of ten children. While Laughlin’s four brothers became osteopathic doctors, Laughlin focused his studies on science education and biology and received his doctorate from Princeton. However, his doctoral thesis on mitotic states of onion root tip cells was scrutinized for putting in little experimental work.

According to Rachel Gur-Arie, “Laughlin was said to strategically put together data to support his claims throughout his career.”[7] In 1910, Charles Davenport asked him to become the superintendent and held that title until 1921, when he was promoted to assistant director until 1939. Laughlin was also a member of the American Eugenics Society, an organization led by members of Yale faculty in New Haven, from 1917 to 1939. His most prominent work was centered on widespread control of birthing in the populations of people he designated inferior through immigration restriction, sterilizations and ban on interracial marriage. These proposed policies most negatively harmed people living with disabilities and foreign-born people, even though he himself had epilepsy.

In 1920, Laughlin testified before the Congressional House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. He argued that immigration from southern and eastern Europe necessitated his desire to survey all mental institutions and charity organizations in the US. In his view, immigrants such as Italians and Jewish people were negatively affecting the genetic makeup of American Yankee stock. Following Laughlin’s testimony, he was appointed by committee chairman Albert Johnson, as the committee’s Expert Eugenics Agent. By 1924, the Immigration Restriction Act followed to control the movement of immigrants arriving to the United States. In addition to his writings influencing the passage of the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924, Laughlin also had an integral role to play in the 1927 Buck v. Bell case. This infamously corrupt case upheld the idea that compulsory sterilization did not violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, a ruling that still carries precedent to this day. Additionally, Laughlin’s work was recognized on the world stage. There is significant evidence that Hitler and the Nazi regime commended Laughlin on his theory of exclusion of whole races of people. “The 1933 Sterilization Laws of Nazi German were sculpted after theories Laughlin had explicated in Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. The University of Heidelberg…granted Laughlin an honorary master’s degree in 1936 for his work.”[8]

This in mind, it is highly unlikely that Governor Cross was not aware of at least a portion of Harry Laughlin’s role in eugenics. By the time Cross commissioned him as the director of the survey, Laughlin already had fifteen years of prominent exposure on the political stage as a purported expert. In the future of this research, there will be a more thorough fact-finding mission to locate any sources that exist pertaining to correspondences between the men and the inception of the survey. The survey was drafted in an office at the state capitol for three years and directed by one of the nation’s most shameful actors, Cross should bear some, if not all, responsibility for this injurious history. Tracing a direct line of communication between the two men would solidify this assertion.

Part I: “Family-Stock Betterment in Connecticut”

The first section of The Survey of Human Resources, outlines the commission’s goals and perceived issues with birth rates in Connecticut in the 1930s. The survey was concluded on October 1, 1938, and its intention was to explain the causes of “degeneracy” and reduce the number of people born with disabilities in the state. They believed it was the state’s responsibility to intervene with the birth rate of the human population and control the “race and inherent qualities of body, mind, and spirit.”[9] Conducting the survey in an office at the state capitol, the commission believed government resources should be reserved for its most physically and mentally capable citizens. They claimed there were foundational human characteristics physical, mental, and spiritual in nature that justified the prevention of residents from parenthood.

Those who were deemed socially inadequate were labeled with the following categorizations: feeble-minded, mentally deficient, people with mental illness, people who commit crimes, drug addiction, people who are blind or those whose vision requires accommodations, people who are deaf or hard of hearing, people who have a speech impediment, physical disabilities, those who are dependent on others and do not have normal family connections, and people in poverty- “due primarily to constitutional lack of initiative, or of physical or mental energy.”[10]

It is essential to note, that at the heart of these arrangements of human bodies, was the determination of identifying which people were employable or unemployable. To eugenicists, there were biological traits of individuals that would cause them to be unemployable and it was up to scientists, doctors and policymakers to breed out these traits to create an industrious nation. “Applied eugenics must be looked to for the elimination of the inborn defects of future generations of the “unemployable” while social welfare and economic opportunity must remedy the environmental cause of normal, effective persons. In any case, those human qualities which underlie “unemployability” must be met by the state as problems in human biology.”[11]

According to Henri Lefebvre, state capitalism carefully organizes systems that benefit the privileged class. Creating competitive academic and scientific spaces, and the daily life of the working class is always under the threat of unemployment which invokes a general sense of terror in urban spaces. Industrialization and urbanization are not separate entities, rather, he invites us to imagine urbanization as the final project of industrialization. “It is essential to aim no longer for economic growth for its own sake, and economistic ideology which entails strategic objectives, namely, superprofit and capitalist overexploitation, the control of the economic (which fails precisely because of this) to the advantage of the State.”[12] As a result, these economic and social systems require structural maintenance in order to assure subordinate power structures.

This analysis of urban space is key to understanding why Laughlin and the commission were concerned with employability when inquiring about residents of the state. In order to maintain the steady stream of labor and labor production, the state asserted it was their responsibility to monitor and control the population to ensure long-term economic gains. The state government believed it was their imperative duty to control the population and movement of people into Connecticut; enforcing immigration policy, dictate who was allowed to marry, how to educate its children, and who could birth children.[13]

Part II: “Eight Handicapped Families of Connecticut in Each of Which Feeble-Mindedness is Common”

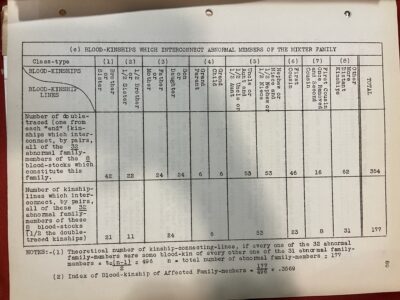

The second part of the survey was concerned with family history studies that were conducted at nearly every state institution. Beginning with one person incarcerated, field workers gathered facts associated with family history, “including the specific diagnoses and measurements and the records of kin and relationship, for each securable near-kin and relative.”[14] The field investigation implemented a data collecting technique designed by the Eugenic Records Office developed by Dr. Charles Davenport in 1910. Social workers at Mansfield State Training School and Hospital of the State of Connecticut began studying economic and family conditions, in an attempt to train and alter the behaviors of patients held at the institution. The survey identifies this study as a collaborative process between field workers, the families studied, and public officers and social organizations to trace kinship ties and marriage relations, medical histories and diagnoses of each individual on the family tree.

The researchers acknowledged there was no biological or concrete distinction between normal and abnormal. Individuals who were automatically categorized as abnormal were those identified as feeble-minded alcoholics, those diagnosed with psychopathy, and individuals with criminal records. Blood-kinship was emphasized as one of the most important types of evidence of feeble-mindedness. “If the casting of the given subject on one or the other side of the dividing line between normal and defective be questioned, there always remains…the subject’s case history with its specific diagnoses and measurements.”[15]

The eight families were not identified and a pseudonym was given in place of their real names. To provide an illusion of scientific authority, the pseudonyms were based on Greek root words. However, some of the Greek etymological translations provided in the study were inaccurate. Pamponer, stemming from the Greek word, Πονηρός (pon-ee-rós) was translated as “utterly depraved,” in actuality it means cunning. Oknos, Οκνός, was translated to “backward” which really means loitering, lazy and dumb. Next, Lagner, Λαγνος (lag-nos) was described as “lewd,” which actually means someone who is attractive or beautiful in a way that elicits a lustful response. Lastly, Xenos, Ξένος, was translated to “guest” but it means foreigner or stranger. The pseudonyms that were correctly translated were, Triakosoy (the three-hundred), Moros (foolish), Anuroy (the discovered), and Mikter (the mixed).[16]

Every family came from what the survey described as “native Yankee stock,” that is, individuals who had ancestry traced back to the first colonizing settlers of the Northeast. According to the survey, the racial groups were composed to reflect the commonwealth of the state. However, it only included two families of Indigenous and/or African descent and one immigrant family from Germany. Its conclusions were that the families studied “show not only trait-descent from foundation stock, but also the biological influence of mate selection among mates available for the marriageable members of the particular central family stock.”[17]

While each family examined provides ample evidence of harmful perspectives about disability, the most striking were the Moros family, Oknos family, and the Anuroy family. Two-hundred and forty-eight people in the Moros family were surveyed and field workers labeled seventy-five of them “inadequate.” Six generations were examined and identified a portion of the family tree that intermarried with people of Indigenous and African descent. The field workers (all white women) determined that the evidence of disabilities in the ancestral lineage was due to miscegenation. “In this case six mentally low-grade bloodlines mixed-by-marriage, and each contributed its own degenerate inheritance to the resulting family-group”[18]

The Oknos family was a smaller family surveyed with only sixty-two people examined. However, it found twenty-four exhibited behaviors described as, “feeble-minded, insane, criminalistic or immoral.” The survey explains the government completely separated members of the family from one another by warehousing them in various institutions throughout the state. One mother was on the waiting list for Mansfield State, her brother in the state prison in Wethersfield for incest, and of her six children, one girl was an inmate at the women’s prison in Niantic, one son at the prison in Cheshire, one girl at Long Lane Farm, one daughter at Mansfield State, one son at Hartford County home and her youngest daughter was in the custody of the state in child services.[19]

The Anuroy family study documented seven generations of a mixed-race family, primarily Anglo, French-Canadian and Indigenous American. The field worker argued that each generation was more degenerate than the next, and referred to the family group as a tribe when talking about members who were disabled. “This tribe (the three family stocks receiving mate-recruits of similar intellectual moral levels) still continues in the production of feeble-minded individuals.”[20] Described as prone to crime, poverty, alcoholism and insanity, the study concluded tracing this family history somehow proved that “family-stock degeneracy is inherent,” and that racial mixing caused degeneracy.[21]

According to Lefebvre, the control of the production of space necessitates the “requirement that the family be rejected as sole center or focus of social practice, for such a state of affairs would entail the dissolution of society; but at the same time that it be retained and maintained as the ‘basis’ of personal and direct relationships which are bound to nature, to the earth, to procreation, and thus to reproduction.”[22] The Survey of Human Resources is evidence that the state government in Connecticut asserted direct control over its residents with disabilities to intervene in the dynamics of family structures to monitor and control the movement and agency of individuals. They recognized the importance of families to maintain the rate of population growth, but believed they needed to intervene in order to conserve productivism and economic advancement. As urban space is produced and manipulated, the same ideology is extended to humans as a method of the “technical domination over nature.”[23]

Further, Lefebvre illuminates the ways urban planning is an ideology and formulates the problems of society and transposes it into spatial terms; this ideology is divisive and pathologized space. Instead of recognizing social illness as a symptom of an ailing society, it identified a distinction between healthy and diseased spaces. Politicians, scientists and physicians have the capacity to conceive of a “harmonious social space, normal and normalizing.” Thus, transforming topographical and ideological space with their dominant social realities.[24] This pathologization of space is evident in the survey, especially when examining the eight families and their ancestral lineage.

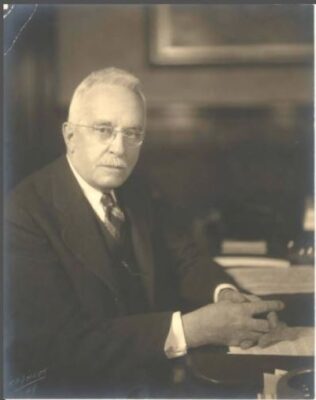

Governor Wilbur Lucius Cross

In 1943, Governor Wilbur Cross published his autobiography, Connecticut Yankee. His choice of the title is important because the definition of a Yankee is one that can either elicit pride or ridicule. In our present-day culture, the term is usually reserved for the baseball team, but in Cross’s time, a Yankee was someone who was a “descendent of colonial settlers who represent a strong connection to early national history. The Yankee is high-minded, humble, steady and inventive.”[25] According to Justin Zaremby, Cross believed a Yankee was both a mindset and a heritage and understanding what that philosophy entails, is the key to understanding Cross.

Entrenched in nostalgia, Cross romanticizes the days of old as simpler times; “as Cross matured into adulthood, the homogenous society in which he was raised was changing. New immigrant groups were beginning to replace the original settlers of English and Scottish descent, and Connecticut’s march to the twentieth century brought new economic and political challenges.”[26] While Cross never mentions The Survey of Human Resources in his book, it is evident that he consigned to the racial animus rampant in the study.

He recognized the value of surveying one’s family history, but in his case, it was to trace the evidence of his haughty excellence. In the first part of the book, Cross weaves literary analysis into the study of his family ancestral history, tracing his roots back to the first colonial settlers of Connecticut. His ancestor, William Cross, came to the Connecticut River Colony in 1637, and settled in what is now Wethersfield. In the spring of his arrival, some members of the Pequot nation conducted a surprise attack and killed a few members of the colony which led to a declaration of war. “On May 11, William Cross, with other men of Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor, enlisted in the war under Capt. John Mason and thus had a share in that terrible massacre of the Pequots in their fort at Mystic.”[27] When he was Governor, Cross gave a public apology to the Pequot tribe for the genocide of their ancestors. However, it wasn’t received well- they laughed in his face and gave him their war whoop in response.

Another descendant, Peter Cross, was a soldier in King Philip’s War and seized land along the Rhode Island border now known as Voluntown. Eventually, Peter Cross and his wife’s family eventually ended up settling in what is now known as Mansfield. “For protection against wandering bands of Indians he built a stockage on a site near the Natchaug River which afforded a clear view up and down the stream and across the meadows.”[28] Eventually, the Cross family settled and built their home in Gurleyville, a village in Mansfield. Gurleyville was named after Wilbur Cross’s ancestor (the great-grandfather of his great-grandfather) Ephraim Gurley.

His maternal lineage was also connected to the Storrs family and they gifted the state the parcel of land that the University of Connecticut now stands on. This family tree is significant to understanding the roots of settler colonialism and its reproductions that created modern society. While Cross and his ancestral lineage have departed from this life, their occupation of stolen lands and the ways in which they transformed space all along the Connecticut River are still visible in the state today.

Sentimentalizing the past, Cross described his early years in Gurleyville as simple and quaint. Townspeople congregated at the two stores on the main road which Cross called “House of Commons” because average, uneducated men congregated and discussed their unfiltered political opinions. However, these days were long gone by the time Cross was in his old age, and he watched the transformation towards urban space with a tinge of resentment despite being an instrumental figure in signaling this change, himself. “The earth now appears to be well-nigh lost for the majority of men and women who live upon it despite the conquest of land, sea, and air since my boyhood.”[29]

When he was in high school, his father passed away and his grief almost led to a mental breakdown. Doctors informed him he was in decline which led him to obsess over disease and sickness, reading every patent medication advertisement he saw. “I attended now and then in Willimantic a spiritualistic seance, open to the public, in which departed spirits tried to converse through professional mediums with their friends in the audience.”[30] It is possible this health scare early in Cross’s life explains his thoughts about health and mental fitness, especially once a teacher of his told him to either “brace up or quit.” After that exchange, Cross vaguely mentions he got control of himself after that conversation and finished high school at the top of his class. In his later years, he briefly mentions the moments in his life when two of his children and wife passed away due to poor health and barely devoted a few sentences describing his grief. It is likely the death of his father was more impactful on Cross’s psyche than he was aware of and deeply shaped his relationship health and wellness.

After Wilbur Cross graduated high school and attended Yale University for his undergraduate and graduate studies, he departed from Gurleyville like many of the young men in his generation, to seek wealth and experience in the city of New Haven. However, there was sorrow in his words when remarking on the move to urban space; realizing that by leaving Gurleyville, it transformed the demographics of the village completely. “As soon as the old folks at home died, the Yankee families met their doom. At first their farmsteads were acquired here and there by Irish and German immigrants; and then in the ‘eighties and ‘nineties of the last century came an invasion of Russian Jews who took up much of the land, not usually for mixed farming, but for the chicken industry. In turn they and their children have largely disappeared, like the Yankees before them, by death and migration to the cities.”[31]

He lamented that a Polish family was cultivating the soil that his grandfather once claimed as his own and the neighbors he knew from his boyhood were now replaced with German and eastern European immigrants. Lefebvre explores this tension and fusion between urban and rural space. “The ‘urbanity-rurality’ opposition is accentuated rather than dissipated, while the town and country opposition is lessened. There is a shifting of opposition and conflict.”[32] The social division of labor becomes dispersed across space but as that process unfolds a contradiction lies in its place. As individuals who called themselves Yankees flocked to the city to shape ideological and economic space, they left their ancestral colonized land, leaving it available for migrants and immigrants to have access to this production of space. In doing so, the line between urban and rural becomes less defined, yet the tensions between the two spaces become contested physically and ideologically.

After graduating and teaching at a number of institutions, he eventually returned to Yale as a professor of English and eventually became the Dean of Graduate Studies. In his capacity as Dean, he was sent to Hawaii because Yale was celebrating the centennial anniversary of the first missionaries, two or three of which were men from the college. Cross recalled his father and uncle had once visited the islands while conducting whaling expeditions. Upon arriving in Hawaii, Cross observed the racial differences compared to life in Connecticut. “Racial antagonism appeared to be nonexistent everywhere we went. Interracial marriages were so common that they seemed at first sight to be the rule.”[33] He explored the garden of the Royal Palace to meet with a women’s group and remarked on the leader of the organization’s physical beauty in a fetishistic manner. “She was part white and part Hawaiian, with perhaps a tincture of Chinese blood. At any rate, she had inherited the best characteristics of the races to which she belonged.”[34] He remarked that the Native Hawaiians of the older generation “in whom not much other blood was infused” he attended one of their outdoor feasts, and observed their stature, “…rotundity seemed to be cultivated by women as a mark of beauty.”[35]

After he feasted on delicacies of the region, he took a tour of a sugar mill. For twenty years he owned stocks in different sugar plantations, after taking the tour of a modern industrialized mill, he decided to buy a few more. The Mayor of San Francisco was supposed to give an address at a luncheon to honor the Admiral and other officers of the Pacific fleet, but he had to decline attendance because he wasn’t feeling well. They asked Cross to deliver the address on Americanization, instead. “ It seemed strange that anybody should be asked to give an address on Americanism while standing by the most conspicuous racial melting pot in these modern times…”

He reminded the audience that their ancestral missionaries learned “that the only way to Americanize an alien race is through the slow process of child and adult education…And so I concluded we still needed good teachers with a notion of what ‘American ideals’ really were.”[36] The Yale trip to Hawaii also had another goal, to establish a partnership with the Bishop Museum of Natural History in Honolulu. Yale was to conduct joint scientific investigations in the Pacific area and Cross coordinated this cooperative research agreement between Bishop Museum and Yale to “research on scientific problems covering Polynesia.”[37] Yale acquired this outpost in the Pacific for scientific research in association with similar institutions in Japan, China, Australia, and New Zealand. In this way, Cross was an instrumental figure in facilitating Yale’s process of globalization and industrialization; expanding the influence of urban space and blurring the lines between nations and people.

When Wilbur Cross became the editor of The Yale Review, he made some changes to the publication to capture a wider audience appeal. He reached out to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes as a contributor and was met with some success. Cross first met Justice Holmes when he was eighteen in Marion, Massachusetts where Holmes had a summer home. As Cross recalls, “I stood by while he and my uncle Franklin Cross greeted each other at the beginning of the season.”[38] Justice Holmes authored the majority opinion for the Buck v. Bell sterilization case where he remarked, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”[39] In the capacity as editor, Cross reached out to Holmes to write an article for the Review. Cross asked him to review a source by William M. Evarts, who defended President Andrew Johnson through his impeachment proceedings, but Holmes declined. “I at once discovered in correspondence with him that he could not write on a subject which, though not at the time controversial, might be regarded as controversial in his historical implications.”[40]

Cross revered the seat of the Governor for as long as he could remember, likening the position to being close to God and angels. During his first campaign as Governor of Connecticut, Cross implemented a slogan whose message reverberates into the modern era, “Back to Normalcy.” When speaking with his associate Nod Osborn about securing the vote of Ku Klux Klan members, Cross said, “What is to be our attitude… towards the Ku Klux Klan, who were then, it was said, burning their fiery crosses on hillside pastures. “Don’t worry, Cross, about Ku Kluxers in the State…I will say nothing for or against them publicly. All I have to do is tell their leaders privately that they have nothing to fear from Cross if he is elected. They will understand. They will line up for you.” Giving the impression he was a protectionist without explicitly saying so was his campaign strategy, and for four terms, this approach worked.[41]

In Cross’s acceptance speech he alluded to eugenics ideology as part of his plan for addressing the economic volatility of the Great Depression. “Action is imperative if the people of the United States are to be kept from degenerating into a nation of gin drinkers with all those biologic, social, and economic disasters which are certain to come in the wake.”[42] In the wake of the 1936 flood, which destroyed parts of the Connecticut River valley, this prompted public works plans such as diverting the Bushnell Park River through an underground tunnel to prevent Hartford from future flooding. Cross also commissioned the construction of the Merritt Parkway, now named after him, in the state. He was keenly aware of the legacy he wanted to leave behind saying, “I liked the idea of going down in history as the Governor of the State who altered the course of Connecticut.”[43]

Herein lies the paradoxical nature of Governor Cross’s life but within this contradiction we see the very reason why he would commission The Survey of Human Resources. In an act to preserve the past, he helped to permanently transform the physical and social geography of the region. Reflecting on the colonial ideological remnants that faded away in Cross’s boyhood because of industrialization, he endeavored to control urban space through a number of methods.

By doing so, he attempted to manifest a mythical past in the urbanized present. He observed the Indigenous land his colonial ancestors seized was now occupied by European immigrants and as a result, the social and political makeup of the state was reshaped. Even though he never mentioned commissioning Harry Laughlin to direct the survey, throughout his autobiography he confirmed social and political values which directly reflect his complicity in the survey’s construction and deployment. Therefore, any attempts to distance Cross from the eugenics movement is historical solecism.

Conclusions:

Governor Wilbur Cross commissioned The Survey of Human Resources because he subscribed to the principles of racial hierarchy found in eugenics ideology. He believed he came from ancestral greatness and the nostalgic past of his youth were the glory days of Connecticut. He longed for a time where pastoral homogeneity reigned, and people of other races were subordinate and assimilated. He attempted to merge this increasingly industrialized world with this mythic perception of bygone days, to assert control over the populations of people in Connecticut living with disabilities. In his capacity as governor, he appointed one of the most infamous eugenicists men of the twentieth century to survey and surveil his citizens, at the same time Hitler was implementing his own genocidal policy. October 1st, the day the survey was drafted, was the day German troops began to occupy the Sudetenland.[44] Like Governor Cross himself, eugenics is a reproduction of a white settler colonial process of spatial production. Categorizing and pathologizing, asserting racial hierarchy and institutional dogma, Cross may have temporarily succeeded in keeping the more controversial parts of his legacy veiled in the shadows. This research, however, makes explicit his connection to both the eugenics movement and the ancestral legacy of settler colonial terror.

[1] Commission Appointed by Governor Wilbur L. Cross, Harry H. Laughlin, Parts I-IV, State of Connecticut: October 1, 1938, Yale University Law Library, The Survey of the Human Resources of Connecticut, Parts I-IV, (New York: Eugenics Record Office, Carnegie Institution of Washington,1938), accessed October 5, 2023.

[2] Laughlin, Harry Hamilton, Part 1, The Survey of the Human Resources of Connecticut, pg.14-15.

[3] Kaelber, Lutz, University of Vermont, Connecticut Eugenics, 2012. https://www.uvm.edu/~lkaelber/eugenics/CT/CT.html.

[4] “Should the Hopelessly Insane Be Put to Death?” Hartford Times, February 27, 1921, CVH Scrapbooks: Departments of Mental Health CSHI/CVH Records, A. Superintendents Scrapbooks Ca. 1867-1896, Accession #90-018, Box 1, Connecticut State Library.

[5] Daly, Mary, “Restrictive Covenants in Property Deeds,” Connecticut Humanities, February 24, 2023, accessed October 4, 2023, https://connecticuthistory.org/race-restrictive-covenants-in-property-deeds/.

[6] Blakemore, Erin, “The Largest Mass Deportation in American History,” History Channel, June 18, 2019, accessed October 4, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/operation-wetback-eisenhower-1954-deportation.

[7] Gur-Arie, Rachel, “Harry Hamilton Laughlin,” Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona State University, December 19, 2014, accessed November 7, 2023, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/harry-hamilton-laughlin-1880-1943.

[8] Gur-Arie, Rachel, “Harry Hamilton Laughlin.”

[9] State of Connecticut, Part 1, The Survey of the Human Resources of Connecticut, pg.1-3.

[10] Ibid, pg. 6.

[11] Ibid, pg. 6.

[12] Lefebvre, Henri, The Right to the City, (Le Droit à la ville), (Mass Market Paperback, 1968,1996), The Anarchist Library, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/henri-lefebvre-right-to-the-city#toc2.

[13] State of Connecticut, Part 1, The Survey of the Human Resources of Connecticut, pg.8-10.

[14]State of Connecticut, Part II, Survey of Human Resources, pg. 3.

[15] Ibid, pg. 17.

[16] Ibid, pg. 16-18.

[17] Ibid, pg. 85-86.

[18] Ibid, pg. 41.

[19] Ibid, 49.

[20] Ibid, 73.

[21] Ibid, 73.

[22] Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space, (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991) pg. 34-35.

[23] Lefebvre, Henri, The Right to the City, pg. 45.

[24] Ibid, pg. 46.

[25] Zaremby, Justin in Connecticut Yankee, An Autobiography by Wilbur Cross, (Westport: City Point Press, 2019, x-xxii.

[26] Zaremby, Justin in Connecticut Yankee, An Autobiography, x-xxii.

[27] Cross, William, Connecticut Yankee, An Autobiography, (Westport: City Point Press, 2019), pg. 3.

[28] Cross, William, Connecticut Yankee, An Autobiography, pg. 5.

[29]Ibid, pg. 28.

[30] Ibid, pg. 57.

[31] Ibid, pg. 63.

[32] Lefebvre, Henri, The Right to the City, pg. 39.

[33] Cross, Wilbur, Connecticut Yankee, An Autobiography, pg. 180.

[34] Ibid, pg. 180.

[35] Ibid, pg. 180.

[36] Ibid, pg. 182.

[37] Ibid, pg. 188.

[38] Ibid, pg. 215.

[39] Member News, “Three Generations, No Imbeciles,” The American Law Institute, April 1, 2022, accessed November 21, 2023, https://www.ali.org/news/articles/three-generations-no-imbeciles/#:~:text=%22Three%20generations%20of%20imbeciles%20are,Bell.

[40] Cross, Wilbur, Connecticut Yankee, An Autobiography, pg. 216.

[41] Ibid, pg. 239-243.

[42] Ibid, pg. 251.

[43] Ibid, pg. 379.

[44] Editors of Legacy Publishers, “Buildup to World War II: January 1931-August 1939,” How Stuff Works, 2023, accessed December 5, 2023, https://history.howstuffworks.com/world-war-ii/buildup-to-world-war-28.htm.